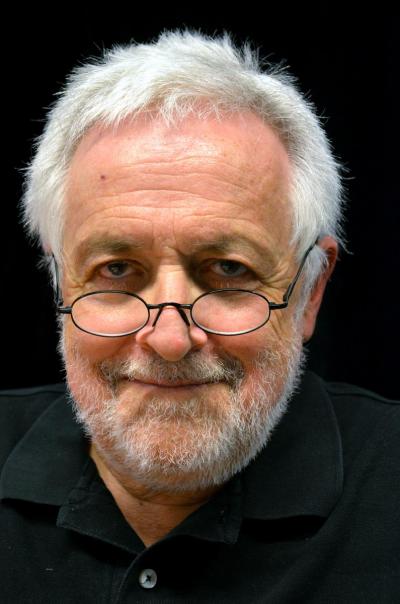

Tomasz Kurianowicz

Tomasz Kurianowicz and his twin sister Katerina were born in Bremerhaven in 1983, but their parents hail from Olsztyn, the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeshipl. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Poland was a poor country compared to today. The socialist economy did not work anywhere near as beneficially as the government repeatedly claimed. Tomasz Kurianowicz’s father had studied viola in Gdansk. He was looking through the job adverts in an international orchestra magazine: Italy, France, Germany – all these countries seem to offer much better prospects than his Polish homeland. And so Janusz Kurianowicz applied for jobs and was accepted by Bremerhaven, which was a prosperous city at the time with excellent prospects. A place in the orchestra there with job security as a municipal employee – that was tempting enough for Janusz Kurianowicz to turn his back on his home in around 1981. However, leaving like that was not without its difficulties. For one thing, to get his passport Janusz Kurianowicz had to sign a blank sheet of white paper. The authorities could later write any text they liked on this sheet and use it against the migrant if they chose to. Also, Janusz Kurianowicz made a commitment to transfer around a quarter of his future gross salary to the Polish state – a type of foreign exchange trade which Poland was using at the time to try and keep its head above water. Janusz Kurianowicz moved to Bremerhaven on his own. It would be another year and a half before his wife, who was also still very young, was to follow him with their young son Piotr, Tomasz Kurianowicz’s brother who was nine years older than him.

The Kurianowiczs spoke Polish at home. Little Tomasz did not learn to speak the language of his country of birth until kindergarten, but he did it easily and naturally. Today, he remembers Bremerhaven as a town influenced by migrants. “As a child with Polish parents I didn’t really stand out”, he said. “Around us, there was a lot of late emigrants from Poland who were all looking to improve their economic prospects. As I recall, they only spoke German and tried not to stand out because they were scared of losing their German citizenship.” Tomasz Kurianowicz’s parents were different. They spoke a lot of Polish and identified very strongly as Poles, even though Janusz Kurianowicz stopped making payments to the Polish state in 1985 thereby forfeiting his right to return. However, he still saw himself as a Pole. His father had fought in the Red Army against the National Socialists and had marched into Berlin with the army. His wife's father had also fought against the Nazis, but on the Allied side. That is why he was later arrested by the Milicja Obywatelska (“Citizens' Militia”) – the official police in the People’s Republic of Poland founded after the Second World War – and sentenced to a stay in the Gulag in the former Soviet Union. These different backgrounds meant that there was plenty for the family to talk about, including the question of whether Poland would have been better to align itself more closely to the West than to Russia. This at least exposed little Tomasz to political issues at an early age but it also gave him the love of music and art that both his parents shared. As a child with an active imagination, Tomasz loved stories and liked to read a lot. When he was young, he wrote little plays that he rehearsed with friends in the country home of a friend’s father. After completing his school-leaving certificate, it was clear to him that he wanted to do something with “writing” and the “fine arts” and he studied literature and musicology at the Free University in Berlin (together with a semester abroad in Zurich). During his time at university, Tomasz Kurianowicz increasingly toyed with the idea of becoming a journalist covering cultural affairs and had already published articles in the Berliner Zeitung, the Süddeutsche and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. These articles had already provided a taster of what he was capable of: He interviewed the pop musician Moby, took a critical look at the RTL format “Teenager außer Kontrolle” and, when the Polish president’s aircraft crashed dramatically, he asked “Poland, what will become of you?“. At the beginning of 2011, with his masters in his pocket, Tomasz Kurianowicz sat in at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung for three months and then worked for a year as a freelance journalist, predominantly for this large Frankfurt daily newspaper.

To this day, the perpetually curious Tomasz Kurianowicz is constantly trying to broaden his horizons. He remained connected after his science degree, began a PhD in literature from the time of Goethe and became a member of the PhD network “Wissen der Literatur” at the Humboldt University in Berlin under the direction of Prof. Joseph Vogl. When the opportunity arose for an exchange scholarship in America, Kurianowicz spontaneously seized it with both hands. From April 2012 to September 2013, he lived in Ann Arbor (Michigan) and was there for the second Obama election in the US. Immediately after this, he got a permanent postgraduate position in the German Department at Columbia University and lived in 112nd Street in Manhattan for three years. He recalls the US as a deeply contradictory country. “I see certain parallels with Poland”, he said. “The extremes between Liberals and Conservatives are more pronounced there as well. And in Poland religion also has an important role to play in many regions. However, in contrast to the US, the Catholic faith dominates.” Kurianowicz was shocked at the poverty which a not insignificant number of US citizens found themselves in. In his eyes, the promise of liberty in the United States is associated with social hardship for large parts of the population, as well as with neglect and a split society. At the end of 2016, he returned to Germany, worked as a freelance journalist again and wrote concert and opera reviews, among others, for the Tagesspiegel, a highly regarded article about the New York art trade for Die WELT, and a hymn of praise for the Austrian band “Bilderbuch” for Die ZEIT. On top of that, he produced television broadcasts for rbb-Kultur and radio broadcasts for radioeins (rbb), Radio Bremen Zwei and Deutschlandfunk Kultur. From October 2017 to June 2018, Tomasz Kurianowicz stood in as editor in the culture section of ZEIT ONLINE. To this day, as well as writing concert and book reviews and generally dealing with feuilleton-style topics, Kurianowicz still repeatedly turns his focus to Poland. Sometimes he writes about the international film festival in Gdansk, sometimes he analyses the efforts made by the Polish Minister of Culture against the liberal theatre scene in his country. He writes about the Polish author Szczepan Twardoch, about the culture war in Poland or conducts an interview with the opposition politician Radosław Sikorski. In doing this, it is very important to Tomasz Kurianowicz that he bring a differentiated picture of the country whose citizenship he holds to German readers. He says: “It bothers me that even today many Germans mainly consider Poles to be backward and reactionary. But in doing so, they overlook time and again the many open, liberal people in Poland.” Kurianowicz also criticises the ignorance towards the complex history of Poland. He visits the country every two months or so. He has friends in Warsaw and Kraków, but often travels to a place near Olsztyn as well, where his parents have a summer house. He loves the warmth of many Poles, the hospitality and the way they live out their traditions positively. He also values a certain melancholy that people in Poland have and, by way of explanation, cites the many misfortunes in Polish history and the fact that for a long time the Poles did not have their own country. “From the Poles’ perspective, the German sometimes come across as somewhat hard hearted”, says Kurianowicz. “So you could say that yes, they’re efficient but that comes at the expense of warmth and openness.” But what Kurianowicz values about Germany is the broad, educated middle class, the generally intellectual climate and the greater divide between religion and state.

2020 was a particularly successful year for the man who is now at the end of his thirties. For one thing, he was able to complete his doctorate. And in July, he started a permanent position as head of the “Society and debate” section for the Berliner Zeitung. He has a big workload. He supervises freelance authors, edits articles, plans part of the newspaper’s content in daily conferences. On top of this, he sometimes writes three or four of his own articles a week. To do this, he has to react quickly to social debates, inform himself and be resolutely active on social media. But there is still enough time for Poland, as the journalist’s more recent articles show. In October, he wrote an essay about his parent’s migration story and his own existence as a German Pole entitled “Deutschland ist … leider geil”. To this day, Tomasz Kurianowicz only has Polish citizenship. Initially, this was his parents’ decision. Then, as a young man, he did not want to give it up. Years later, when Poland joined the EU and EU membership made it possible to have dual nationality, his attitude changed and he wanted to apply for German citizenship as well. But he only got around to applying for it when he was studying for his doctorate in New York. What he could not have known was that his long stay overseas would mean that he forfeited the right to German citizenship. “At the citizen’s advice centre I was told that for an application for German citizenship to be successful, you must have paid tax in Germany for four years continuously", said the journalist who loves to travel. “My stay in America meant that this was not the case. So I let it go.”

Anselm Neft, November 2020

The homepage of the journalist Tomasz Kurianowicz: www.kurianowicz.com