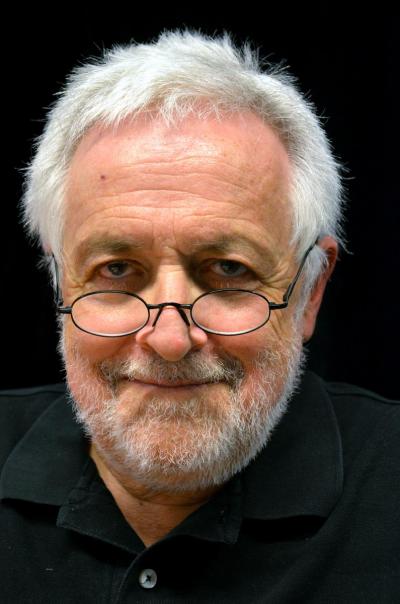

Tomasz Kurianowicz

Tomasz Kurianowicz and his twin sister Katerina were born in Bremerhaven in 1983, but their parents hail from Olsztyn, the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeshipl. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Poland was a poor country compared to today. The socialist economy did not work anywhere near as beneficially as the government repeatedly claimed. Tomasz Kurianowicz’s father had studied viola in Gdansk. He was looking through the job adverts in an international orchestra magazine: Italy, France, Germany – all these countries seem to offer much better prospects than his Polish homeland. And so Janusz Kurianowicz applied for jobs and was accepted by Bremerhaven, which was a prosperous city at the time with excellent prospects. A place in the orchestra there with job security as a municipal employee – that was tempting enough for Janusz Kurianowicz to turn his back on his home in around 1981. However, leaving like that was not without its difficulties. For one thing, to get his passport Janusz Kurianowicz had to sign a blank sheet of white paper. The authorities could later write any text they liked on this sheet and use it against the migrant if they chose to. Also, Janusz Kurianowicz made a commitment to transfer around a quarter of his future gross salary to the Polish state – a type of foreign exchange trade which Poland was using at the time to try and keep its head above water. Janusz Kurianowicz moved to Bremerhaven on his own. It would be another year and a half before his wife, who was also still very young, was to follow him with their young son Piotr, Tomasz Kurianowicz’s brother who was nine years older than him.

The Kurianowiczs spoke Polish at home. Little Tomasz did not learn to speak the language of his country of birth until kindergarten, but he did it easily and naturally. Today, he remembers Bremerhaven as a town influenced by migrants. “As a child with Polish parents I didn’t really stand out”, he said. “Around us, there was a lot of late emigrants from Poland who were all looking to improve their economic prospects. As I recall, they only spoke German and tried not to stand out because they were scared of losing their German citizenship.” Tomasz Kurianowicz’s parents were different. They spoke a lot of Polish and identified very strongly as Poles, even though Janusz Kurianowicz stopped making payments to the Polish state in 1985 thereby forfeiting his right to return. However, he still saw himself as a Pole. His father had fought in the Red Army against the National Socialists and had marched into Berlin with the army. His wife's father had also fought against the Nazis, but on the Allied side. That is why he was later arrested by the Milicja Obywatelska (“Citizens' Militia”) – the official police in the People’s Republic of Poland founded after the Second World War – and sentenced to a stay in the Gulag in the former Soviet Union. These different backgrounds meant that there was plenty for the family to talk about, including the question of whether Poland would have been better to align itself more closely to the West than to Russia. This at least exposed little Tomasz to political issues at an early age but it also gave him the love of music and art that both his parents shared. As a child with an active imagination, Tomasz loved stories and liked to read a lot. When he was young, he wrote little plays that he rehearsed with friends in the country home of a friend’s father. After completing his school-leaving certificate, it was clear to him that he wanted to do something with “writing” and the “fine arts” and he studied literature and musicology at the Free University in Berlin (together with a semester abroad in Zurich). During his time at university, Tomasz Kurianowicz increasingly toyed with the idea of becoming a journalist covering cultural affairs and had already published articles in the Berliner Zeitung, the Süddeutsche and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. These articles had already provided a taster of what he was capable of: He interviewed the pop musician Moby, took a critical look at the RTL format “Teenager außer Kontrolle” and, when the Polish president’s aircraft crashed dramatically, he asked “Poland, what will become of you?“. At the beginning of 2011, with his masters in his pocket, Tomasz Kurianowicz sat in at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung for three months and then worked for a year as a freelance journalist, predominantly for this large Frankfurt daily newspaper.