Madame Szymanowska and Goethe – a burning love?

It is no secret that Goethe met the internationally renowned Polish pianist Maria Szymanowska and her sister Kazimiera Wołowska in August 1823 in the Bohemian health resort of Marienbad and some time later in Weimar. Nor is it a secret that he dedicated poems to both women, works of world literature whose first few lines are still quoted today. “Passion brings reason! – Who can pacify / An anguish'd heart whose loss hath been so great?”, he wrote for Szymanowska and created a lasting monument to her piano playing: “And then was felt, – oh may it constant prove!

– / The twofold bliss of music and of love.” He dedicated the following lines to her sister: “Your testament gives out the comely gifts, / With which mother nature completes you” and praised any man to whom she may belong in the future as fortunate: “But if you aspire to make a happy man, / It would be he to whom you give yourself completely.”

Both poems were published with the respective dedications “To Madame Marie Szymanowska” and “To Miss Kasimira Wolowska” 1828 in the earliest edition of “Goethes Werken. Vollständige Ausgabe letzter Hand” by Cotta in Stuttgart and Tübingen in the fourth volume in the section “Inschriften”.[1] The three verses for Szymanowska had already been printed, without the dedication, in the “Lyrisches” section in the third volume under the title “Aussöhnung” [“Atonement”] as a third part of the “Trilogy of Passion” following the poems “To Werther” and “Elegy”.[2] The most well known part of this trilogy is the middle part, which is known today as the “Marienbad Elegy”.

Readers first heard about Goethe’s personal appreciation of the Polish pianist in 1834 when correspondence between Goethe and the musician and composer Carl Friedrich Zelter, to whom Goethe had written on 24 August 1823 from Eger in Bohemia, was published by Goethe's secretary Friedrich Wilhelm Riemer: “In a completely different sense and yet with the same effect on me, I heard Mad. Szymanowska, an unbelievable pianist; she may be placed alongside our own Hummel, save that she is a beautiful amiable Polish woman […]; however, if she stops [playing] and comes and looks at one, one does not know whether one should consider oneself fortunate that she has stopped? Treat her with kindness when she comes to Berlin […]”.[3] Goethe had been dead for two years when the correspondence was published. Szymanowska had died a year before him.

The meeting between Szymanowska and Goethe was subsequently included in early Goethe biographies. In his principle work “The Life of Goethe” (1855), the London author, literary critic and philosopher George Henry Lewes reported that it was not just Goethe’s Marienbad favourite, Ulrike von Levetzow, who had been fascinated by the “eloquent, old gentleman”: “Madame Szymanowska, according to Zelter, was ‘madly in love’ with him; and however figurative such a phrase may be, it indicates, coming from so grave a man as Zelter, a warmth of enthusiasm one does not expect to see excited by a man of seventy-four.“[4]

In 1887, the lawyer and Goethe researcher Gustav von Loeper published an extensive treatise on the “Trilogy of Passion” in the Goethe-Jahrbuch in Frankfurt am Main, in which he described and analysed the circumstances of its creation, the connection with Szymanowska and her sister, and Goethe’s diary entries.[5] Two years later, the Masurian literary historian Gustav Karpeles dedicated an extensive essay entitled “Eine Freundin Goethes” to the connection between Szymanowska and Goethe in the Neue Musik-Zeitung, which was published in Stuttgart and Leipzig.[6] In his book “Goethe in Polen”, the same author disclosed more quotes from Goethe’s letters to the Weimar State Chancellor Friedrich von Müller in the chapter “Marie Szymanowska und ihre Beziehungen zu Goethe”.[7] Since then, much has been written about the connection between Szymanowska and Goethe, both in Germany and in Poland, in part because letters that had long been overlooked recently surfaced again.[8] It is also interesting to hear which other personalities in Germany Szymanowska was in contact with and where she gave her concerts, and how the German public reacted to her music.

When Maria Szymanowska arrived with her brother and sister in Marienbad, where she registered in the “List of spa guests” under the entry from 8 August 1823 as the “first pianist of her Majesty the Empress of Russia”, (see PDF 1),[9] despite her prestigious Russian accolade and 10-year marriage she was still at the beginning of her international career and was on her first European tour. Born in Warsaw in 1789 as the seventh of ten children of the well-to-do brewery owner Franciszek Wołowski and his wife Barbara, née Lanckorońska, she had her first piano lesson at the age of nine with a certain Antoni Lisowski, switching to Tomasz Gremm after two years. The family regularly had a circle of musicians and literarti as their guests and welcomed to their salon any composers and instrumentalists who were passing through, including Ferdinando Paër, Daniel Steibelt, Pierre Rode, August Alexander Klengel and even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with his son Franz Xaver, who gave a concert in the Warsaw National Theatre in June 1819 and wrote a dedication to Szymanowska in her poetry and scrapbook.[10] From 1804, Maria took composition lessons from the German composer from Silesia Joseph/Józef Elsner. From 1805 to 1806, she was a member of a Music Society that Elsner had founded with the German author E.T.A. Hoffmann. In 1809, the twenty-one-year-old gave her first concert in Warsaw before leaving for Paris where she gave concerts in salons. She introduced herself to the Director of the Paris Conservatory, the composer Luigi Cherubini, who praised her playing and dedicated a piano fantasy to her for her scrapbook.

In the same year, she married the estate tenant Teofil Józef Szymanowski, who showed no understanding for her piano playing or for her composing and she tried, in vain, to be interested in the work on his estate. Although he found her public performances indecent, she also managed to make a name for herself in Warsaw. In 1812, the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung published by the Leipzig music publishers Breitkopf und Härtel reported the following: “Warsaw. There is very little musical news here now; it seems as if the art has been buried. […] The local orchestra is now poorly appointed […] there is little private music […] Of note amongst the pianists are: The wife of Dr Wolff, Mad. Kaminska, Mad. Szymanowska, and Mad. Richter.”[11] In 1811, Szymanowska had twins called Helena and Romuald, and in 1812 her daughter Celina was born, who would go on to marry Poland’s national poet Adam Mickiewicz in 1834. In 1815, she gave concerts during the Congress of Vienna, in 1817 in Dresden, in 1818 in Vienna and London, and in 1820 in St. Petersburg and in Berlin (Fig. 1).

In 1819/20, Breitkopf & Härtel published six albums containing a total of sixty nine pieces that she had composed for piano[12] and which were dedicated to relatives, friends and other high-ranking personalities, including the Polish Prince Anton Heinrich Radziwill/Antoni Henryk Radziwiłł, Prussian governor in Poznań and member of the Prussian State Council, who was resident in Berlin(Fig. 2). Radziwill was himself a committed cellist and composer and had been working on a score for Goethe’s “Faust” since around 1810, a task that had apparently been conferred on him by Goethe’s friend Zelter. The Italian opera singer Angelica Catalani, who performed in Warsaw in November 1819, is said to have pushed Szymanowska to decide against her marriage and to opt for a career in music, whereupon Szymanowska filed for divorce. For two years, she worked on her piano technique, expanding her repertoire, teaching and giving concerts. In 1822, she gave a guest performance in St. Petersburg, where, after performing at the Czar’s summer residence, the title of First Court Pianist to the Czar’s mother and to Czar Elisabeth Alexejewna was bestowed upon her, a title which not only brought with it considerable prestige, but also solid annual financial support.[13] (PDF 2)

In February 1823, she undertook a concert tour through the Ukrainian towns of Kiev, Tultschyn, Schytomyr, Dubno, Kremenez and Lviv. After returning temporarily to Warsaw, where she gave a concert in May, she went on tour through Europe accompanied by her sister and her brother, who was responsible for organising the travel and the concerts. She gave concerts in Germany until the end of the year: Dresden in January, Leipzig in autumn, and Weimar, Dessau, Braunschweig and Berlin in the winter months. At the beginning of her concert tour, which was to take three years in the end, she travelled to Poznań in Prussia where she is said to have played a concerto by Johann Nepomuk Hummel and her own “Fantasie” on 29 and 30 June, as was reported by a Warsaw newspaper.[14]

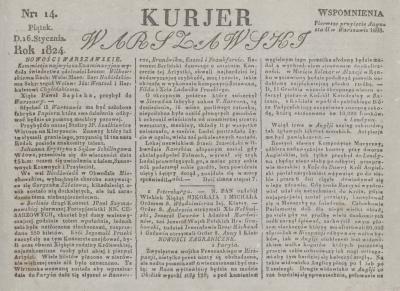

She then travelled to Carlsbad in Bohemia, which at this time was already considered one of the most famous bathing towns in Europe[15], arriving on 6 July. Fourteen days later, on 21 July, as the Warsaw daily newspaper Kurjer Warszawski reported two weeks later, she gave a concert there in front of eminent personalities, including the Princess of Cumberland and around fifty Dukes and Duchesses. The number of Poles attending the concert, who were also visitors to the spa town, was no less than double this amount. Each of the recitals by the extraordinarily talented artist was met by rapturous applause. Before that, the famous Hummel had played a concert in Carlsbad, but he had attracted a smaller audience (PDF 3).[16] In truth, however, the stay in Carlsbad was really meant as a treatment for Szymanowska’s sister who was taking the baths because of a pain in her side, which Szymanowska reported in a letter to Pjotr Andrejewitsch Wjasemski, the author and friend of Alexander Puschkin, who was living in Moscow. She also wrote to him that she planned to meet Goethe in Marienbad and then to travel on to Dresden and Berlin.[17]

Just why Szymanowska sought Goethe’s friendship is not known. At any rate, on 8 August she and her sister travelled to Marienbad. At this time, Marienbad in the Austrian Crown land of Bohemia, was an aspiring spa town that was still very much under development. In 1808, on the initiative of the Tepl Premonstratensian monastery, the first bathing house had been built on the sulphurous “Maria” source fourteen kilometres west, which, with its surrounding healing springs, had been known since the Middle Ages. Following publications by the monastery doctor about the healing effect of the sources, a health resort, initially consisting of half-timbered houses, was set up in 1813 (Fig. 3). In the first season in 1815, seven buildings were available to the guests as accommodation.[18] In 1818, the health resort, which was named Marienbad after the source, was officially recognised. By 1820, classical pavilions had been erected at the fountains and at the viewpoints, parks had been created and prestigious spa buildings and hotels had been built (Fig. 4). However, it was still possible to experience the original idyll of the valley in the Kaiserwald (Fig. 5). In 1824, the site already had forty buildings and had a good reputation as a healing sanatorium for guests who also travelled to take the waters in nearby Carlsbad, which was much older, or to the other sites around Eger.[19]

In the period in question, high-ranking European society consisting of around eight hundred spa guests would frequent Marienbad. In August 1823, for example, to name just a few of the guests from the first eleven days of August when Maria Szymanowska and her siblings arrived, the guests included Ludwig Baron von Mannsbach, government assistant lawyer from Greiz, the Polish Division General Jan Nepomucen Umiński from Poznań, the “true Russian wife of the privy council from Kurland”, Charlotte Baroness von Hahn, Baroness Bernhardine von Aachen from Westphalia, a Kajetan von Szydłowsky, “landowner and knight of the Polish Order, from Warsaw”, Ferdinand Baron von Reiboldt, “Saxon secret finance officer, with wife, née Baroness Pflugk, and daughter, from Dresden”, a Bavarian lieutenant, a tutor from Greiz, a royal Bavarian Judge at the Higher Appeal Court with wife from Munich, merchants and noblemen from Prague and Berlin, the “chamberlain and estate owner” Leopold Count Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau from Vienna, a lawyer with wife from Budweis, a Count von Mycielski, landowner from Poznań, a Baron Skórzewski, “Landowner from Ekelmo (sic!, presumably Chełmno) in Pohlen” and opera singer Anna Milder, who had travelled from Berlin. People had a choice of living in the inns Zum Stern, Zum Prinzen, Zur Goldenen Sonne, Zur Goldenen Krone, Zum Schwarzen Adler, Zur Goldenen Traube, Zum Goldenen Falken, Zum Goldenen Löwen, Zum Weißen Schwan, like Szymanowska and her siblings in Klingers Gasthof, in the Sächsisches or in the Russisches Hause, in the hotels Zum Römer, Zur Stadt Dresden, Zum Grünen Kreuze or in the bathhouse.[20]

Goethe (Fig. 6-8), who, between 1785 and 1820, had been to take the waters in Carlsbad twelve times and in the Giant Mountains and in Teplitz once each,[21] then spent three summers in Marienbad. During his first stay since 29 July 1821, he took accommodation in “Brösigke’sches Haus”, a prestigious hotel with one hundred rooms over three floors (Fig. 9), which was run by Amalie von Levetzow and her parents, Mr and Mrs Brösigke. Goethe met the “sophisticated and pleasant” Mrs von Levetzow for the first time in Carlsbad in 1806 and was inspired by her to create his dramatic festival “Pandora” (1808). After the divorce from her first husband and the loss of her second husband at the battle of Waterloo, she used the rest of her fortune to build the hotel in Marienbad with her parents for select resort guests to stay; her family then also lived in the hotel. When they ran out of money, the high-ranking Austrian government official Franz von Klebelsberg zu Thumburg jumped in and was registered as an owner. He would soon became Amalie’s lover and later her husband, and the house was also named “Palais Klebelsberg” after him.[22]

Goethe was welcomed into the Brösigke family from the very start. The seventy-two-year-old, whose wife Christiane, née Vulpius, died in 1816 and who became seriously ill in spring 1821, quickly developed a deep affection for Ulrike (Fig. 10), the eldest of the three daughters of Amalie von Levetzow. The seventeen-year-old, who had only just come back from finishing school in Strasbourg, initially saw in the poet and Weimar minister, who until then had been unknown to her, just a lovable old man whose continuous attention flattered her. Summer 1822, the whole of which Goethe spent with the Brösigke family, fired up his love for Ulrike von Levetzow. He accompanied her on walks and outings, danced with her at balls and gave her presents. She, it is said, “felt a girlish affection for Goethe, a love such as an eighteen-year-old shows to someone who spoils her in a fatherly-manly way.”[23]

In August 1823 – this time Goethe was living in the Zur Goldenen Traube, whilst his sovereign, Grand Duke Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, with is entourage alighted in the “Graf klebelsbergisches Hause”[24] – Goethe’s love for Ulrike blossomed to an obsession from which only a marriage proposal could release him. The Grand Duke himself asked Frau von Levetzow for her daughter’s hand for Goethe, whilst the high society between Bavaria, Thüringen and Prussia, Marienbad, Carlsbad and Vienna, and especially Goethe’s son August and his wife Ottilie in Weimar, were extremely alarmed due to the impending disparate match. However, Ulrike, who later and right into her old age insisted that: “It was not a love affair”, had her mother communicate that she could not imagine such a match because Goethe lived together with his son and daughter-in-law in Weimar and could not bear to be separated from her own family.[25]

Whilst Goethe still hoped and did not want to admit to himself that his desire to marry would not come to fruition, he met ladies, who were also attractive to him and who could help him through his incipient heartache. The twenty-three-year-old Lili Parthey arrived in Marienbad from Berlin. She was the granddaughter of the Berlin author and publisher Friedrich Nicolai, student of Zelter and was acquainted with the Mendelssohn family and with Prince Radziwill, who was still working on the score for “Faust” and would continue to do so right up into the 1830s. She conveyed greetings and a kiss from Zelter and fell spontaneously in love with Goethe, whilst he reported to Princess Pauline von Hohenzollern, who had arranged the meeting, that the quite amorous encounter could have ended “very badly and dangerously”.[26] Goethe also spoke to Maria Szymanowska, in his poem dedicated to her, about “the twofold bliss of music and of love”, whereby she perhaps already guessed that his love was promised to another.[27]

He mentioned Szymanowska and her sister for the first time in his diary on 14 August. After discussions with Baron von Manteuffel and Major von Wartenberg, he met the pianist on that day, presumably at the concert that he told Zelter about in a letter ten days later. “With Madame Szymanowska, who played the piano in a neighbouring house, a piece by Hummel, one of hers and another two, really wonderful. Walked with her towards the mill. The rain ambushed us. With umbrellas to the source. In the evening on the terrace.”[28] The day after that and the day after that, he wrote the poems for the two sisters, transferred them into two albums on the third day, and then presented them, presumably in French[29]: “Poems accomplished and written in the two albums. Madame Szymanowska visited me. Curious about the contents of the album.”[30] Looking through the diary, there were no further meetings until 20 August and 4 September because Goethe had now travelled to Eger and to Carlsbad, partly to learn about geology and to complete his mineral collection. On 7 September, Szymanowska had obviously left Marienbad without having seen Goethe again, because he noted: “Found Madame Szymanowska’s embroidered plate Similarly other sent in during my absence.”[31]

Goethe also told other people he wrote to about the Polish pianist. On 18/19 August, he wrote the same lines to his daughter-in-law Ottilie and to the Berlin lawyer, philologist and State Councillor Christoph Ludwig Friedrich Schultz: “Madame Szymanowska, a female Hummel with the easy Polish manner, has made me extremely happy these last few days; behind the Polish amiability was the greatest talent, just as a foil so to speak or […] vice versa. The talent would overwhelm you, if it were not for her charm.”[32] He allowed his son August to see his heartache, which had been caused by Ulrike and eased by the two musicians Anna Milder-Hauptmann and Szymanowska: “There is just a certain irritability left over, which I only became aware of when listening to music, without Mmes Milder and Szymanowska, I would never have done that.”[33] The composer and pianist Johann Nepomuk Hummel, who, it should be added, was a student of Mozart, Antonio Salieri and Haydn, was court conductor in Weimar from 1819 and one of the best known personalities in the city. According to the musicologist Joel Sachs, no tourist’s visit to Weimar would have been complete without having seen Goethe and heard Hummel playing.[34] Szymanowska probably met Hummel in St. Petersburg in 1822, where he was playing concerts at the same time as Szymanowska on his only trip to Russia, as was reported by the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung.[35]

In a new letter to Schultz, Goethe talked about the poems that he had since written, and wrote about Szymanowska’s departure from Marienbad: “In passing, I managed several poems which are of value to me and should hopefully not remain without value for friends. I cannot expect any more, particularly as many other good things, like the incredible expression of talent by the pianist Madame Szymanowska, cannot be captured in words. She has gone on her way to Berlin; if you should see or hear the woman, who is as amiable as skilful, you will not blame me for having been captivated by her.”[36] On the following day, Goethe wrote to the Frankfurt banker, author and theatre promoter Johann Jakob Willemer and his wife Marianne: “Madame Szymanovska from Warsaw, the most skilled and delightful pianist, has also stirred up something quite new in me. One is astonished and delighted when she handles the piano and when she stands up and comes towards us with all amiability, one enjoys that just as much.”[37]

Following his return to Weimar on 13 September 1823, Goethe shared the poem for Szymanowska with his closest friends. On 25 September, Chancellor von Müller stated: “I was with Goethe from 5 - 8 o’clock, and his conversation was extremely interesting, confidential and warm-hearted. […] He showed me the poems to Madame Szymanowska, the virtuoso, and to her sister. She is like the air, so circumfluent, so quick to sit, so everywhere, so light and, so-to-speak incorporeal. He showed me her handwriting. […] When I asked a few tricky questions about the virtuoso Szymanowska, he berated me softly: Ach the Chancellor often displeases me unexpectedly. There was not a trace of ill-humour or displeasure to be found in him the whole evening…”[38] After Szymanowska arrived in Weimar on 24 October to visit Goethe for almost two weeks, Johann Peter Eckermann, who was his right-hand and would later be his executor, noted: “He said a young Polish woman has arrived who will play something on the piano. I happily accepted the invitation. […] And what did he present to me? His newest, most favourite poem, his ‘Elegy’ from Marienbad. […] When I had finished reading, Goethe came up to me again. ‘So’, he said, ‘I have shown you something good there.’”[39]

Years later, in December 1831, he told Eckermann the full story of how the three poems that make up the “Trilogy of Passion” had come to be. It was not originally conceived as a trilogy, but “rather it became a trilogy gradually and to a certain extent by chance. At first, as you know, I just had the ‘Elegy’ as an independent poem in its own right. Then Szymanowska, who had been in Marienbad with me during the same summer, visited me and as a result of her charming melodies awoke in me an echo of those blissful days of youth. The stanzas that I dedicated to this friend are, therefore, versed in the metre and tone of that ‘elegy’ and join with this almost automatically as a conciliatory ending. Then Weygand wanted to organise a new edition of my ‘Werther’ and asked me for a preface which was then a very welcome opportunity for me to write my poem ‘An Werther’ [‘To Werther’]. And because I still had a residue of that passion in my heart, the poem automatically became an introduction to that ‘Elegy’. And so it came to pass that all three poems that now stand together were permeated by the same feelings of heartache and that ‘Trilogy of Passion’ came into being, I do not know how.”[40] However, this chronology cannot be correct because the poem “Atonement”, which was dedicated to Szymanowska, was written before 18 August 1823, whilst “Elegy” [“Elegie”] was written in the September and October of the year before Szymanowska’s arrival in Weimar and was still being proofread a number of times at the end of November.[41] In March 1824, the poem “To Werther” then followed on the occasion of the Leipzig anniversary edition of the “Leiden des jungen Werther” [“The Sorrows of Young Werther”] that was published for the first time in 1774.

In the final version, therefore, Goethe’s “Trilogy of Passion” spans his entire life. In what is now the first poem of the trilogy, “To Werther”, Goethe resurrects the passionate and unhappy lover fifty years ago: “Once more, then, much-wept shadow, thou dost dare, / Boldly to face the day's clear light”, to then remember at the end the suicide of the unfortunate one: “How moving is it, when the minstrel sings, / To 'scape the death that separation brings!” By contrast, the “Elegy” is pervaded completely by Goethe’s loss of his most recent love, Ulrike von Levetzow, whom he never saw again after he left Marienbad. It is despair and torment from the very first lines: “What hope of once more meeting is there now / In the still-closed blossoms of this day?” right to the end of the twenty third verse: “They urged me to those lips, with rapture crown'd, / Deserted me, and hurl'd me to the ground.” The third poem devoted to Szymanowska finally brings atonement from the sufferings of passion through the power of music which is capable of the following: “To pierce man's being to its inmost core / Eternal beauty has its fruit to bear”. According to the literary scholar Josef Kiermeier-Debre, Goethe, whose relationship to music had been problematic, had “for the first time, in his encounter with the Petersburg Court pianist Maria Szymanowska and the singer Anna Milder-Hauptmann (1823) and while suffering the loss of Ulrike von Levetzow, understood music to be that which it had always been for his great antipode Jean Paul: a force like love, expression of the fundamental elegiac mood of the world and at the same time relief from this its reflexive sensitivity.”[42]

Atonement [to Madame Marie Szymanowska]

Passion brings reason—who can pacify

An anguish'd heart whose loss hath been so great?

Where are the hours that fled so swiftly by?

In vain the fairest thou didst gain from fate;

Sad is the soul, confused the enterprise;

The glorious world, how on the sense it dies!In million tones entwined for evermore,

Music with angel-pinions hovers there,

To pierce man's being to its inmost core,

Eternal beauty has its fruit to bear;

The eye grows moist, in yearnings blest reveres

The godlike worth of music as of tears.

And so the lighten'd heart soon learns to seeThat it still lives, and beats, and ought to beat,

Off'ring itself with joy and willingly,

In grateful payment for a gift so sweet.

And then was felt,—oh may it constant prove!—

The twofold bliss of music and of love.

After her departure from Marienbad on 7 September 1823, Szymanowska and her siblings travelled to Dresden and Pillnitz via Jena. As the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung reported, in Dresden she performed at the “Hôtel de Pologne at increased prices”: “She played the first movement of Hummel’s Concerto in H minor, then the Adagio and Finale from the same master’s A minor Concerto, and finally a Rondo in C major by Field. She has a magnificent firm touch to her instruments, combined with tenderness and much expression. Although she took the tempo of the Hummel compositions somewhat more slowly than the composer would like, her playing had more clarity as a result. She played the Rondo by Field with great skill and with all the idiosyncrasy that the compositions by this master demand.”[43] The Kurjer Warszawski reported that the owner of the hotel, a friendly Pole, had let the pianist have the lighting in the room free of charge.[44] She then performed before the king, his family and the court in the summer residence of the Saxon court in Pillnitz. In the same article, the Kurjer Warszawski continued that the monarch had shown himself to be extremely pleased with the concert and had bestowed high praise upon the artist.[45]

Szymanowska then travelled to Berlin. On 2 October, she and Kazimiera wrote to their sister Teresa in Warsaw about the numerous events that they had attended. There were balls every evening and even masquerades. Kazimiera reported on a performance of the opera “Libussa” by Conradin Kreutzer and on the preparations for Szymanowska’s concert on 10 October in the Königlichen Schauspielhaus, which the theatre’s general manager Carl von Brühl wanted to strongly support. Szymanowska added that they intended to visit the Berliner Singakademie with “the Mendelssohns”. At her concert, which Carl Moeser, who would later be the Royal music director, conducted, she played a piano concerto by Hummel, a rondo by Klengel and an adagio by the pianist and composer Friedrich Kalkbrenner, who she was personally acquainted with and who also visited the Mendelssohn’s at home.[46]

Szymanowska must have continued on to Leipzig the next day, where she gave concerts on 13 and on 20 October. Kazimiera wrote to her parents in Warsaw to tell them that the first concert at which the piano concert by Hummel was once more on the program attracted an audience of more than seven hundred. It was the talk of the town. The pianist and composer Friedrich Schneider, Court Conductor from Dessau, who performed in Leipzig the next day, praised Szymanowka’s talent. On the second date, she played a concerto by Klengel, the Sixth Rondo by Field and a septet and a new rondo by Hummel. The music publisher C.F. Peters requested the new rondo so that the music scores would sell better.[47] The Journal für Literature, Kunst, Luxus und Mode published in Weimar summarised by saying: “On 13 Oct. a pianist, Madam Szymanofska, played in a subscriptions concert in Leipzig. She is, without doubt, the most sublime and brilliant pianist that there currently is. Everyone who heard her practising in the days before were captivated by her performance. […] (We reproduce this from a letter from Leipzig, which adds: ‘Mad. S. should be a Polish Countess and will also visit Weimar’.)”[48]

The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung reported: “On 20 October, Mad. Szymanowska, first pianist to her Majesty the Empress of Russia, provided us with the most wonderful enjoyment. […] Mad. Szym. is a master of her instrument in the whole sense of the word. Skill and musical spirit are equally strong in her. […] Then the latest Rondo brillant by Hummel, a very rewarding composition, was performed by her with such certainty in strength and tenderness that the whole room resounded with the roar of the applause. Her playing was not overloaded; each tone is just as it should be …” (PDF 4).[49] The Abend-Zeitung published in Dresden wrote about the two concerts in Leipzig: “Mad. Maria Szymanowska … performed… first in a subscription concert and gained so much acclaim from her splendid playing that, when it came to the concerts that she herself later arranged, the room could hardly contain the numbers streaming in, a case, which is extremely rare in Leipzig where one is overloaded with music. Lay persons and connoisseurs were captivated by the precision and the expression of her playing and the latter claim it is an even greater joy to see her playing close up and to marvel at the agility of her fingers and her original fingering, which deviates completely from conventional rules. In private circles Mad. Szymanowska is also said to have bewitched through ingenious fantasies on the piano …”[50]

On 24 October 1823, Szymanowska “coming from Dresden and Leipzig” with her sister and brother, as Goethe noted in his diary,[51] arrived in Weimar and caused a sensation there as well. Chancellor von Müller noted: “Goethe held a large evening event to honour that interesting Polish virtuoso, Mad. Marie Szymanowska, about whom he has already told us so much and who arrived here yesterday with her sister Casimira Wolowska to visit him. He wrote the beautiful and emotional verses to her in Carlsbad (sic! Marienbad) which he recently read out to us and which express his thanks that her soulful playing brought peace to his soul again when the separation from Levezow had caused such a deep wound. Goethe was very cheerful and gallant the whole evening, he dined out on the general applause that Mad. Szymanowska received as much through her personality as through her soulful playing.”[52]

Every lunchtime, Szymanowska and her siblings ate with Goethe, whilst the pianist returned the favour by playing table music. On 27 October, Goethe again sent out an invitation to a musical evening: “Preparation for the evening concert. […] The crowd arrived gradually. Madame Szymanowska played. Madame Eberwein sang accompanied by string and brass instruments. Stayed until nearly 10 o’clock”, wrote Goethe in his diary.[53] Eckermann commented: “The following day I was told that the young Polish lady, Madame Szymanowska, in whose honour the festive evening had been held, played the piano quite masterfully to the delight of the entire crowd.”[54] The next day, according to Chancellor von Müller, there was another “concert at Goethe’s. A quartet from the composition of Prince Louis Ferdinand and played by Mad. Szymanowska gave Goethe the opportunity to make the most interesting comments. He conceived the idea, almost shyly you might say, that the artist should give a public concert and asked Schmidt, Coudray and myself to promote it in every way.”[55] On 30 October there was also “A concert at Goethe’s in the evening”[56]

The public concert inspired by Goethe was able to take place on 4 November “in the chamber of the town hall before what was, by local standards, a very large audience, after Grand Duchess Maria Pawlowna, the daughter-in-law of Grand Duke Carl August, had loaned out her own instrument“.[57] The Journal für Literature, Kunst, Luxus und Mode (PDF 5) reported extensively on the concert in which vocal soloists and members of the court orchestra also performed. Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony in B major, the Piano Concerto in A minor by Hummel, a piano quintet by Beethoven, vocal pieces by Ferdinando Paër, a piano nocturne by John Field and a rondo from the First Piano Concerto by Klengel: “the outstanding artist was rewarded with general, rapturous applause. She performed Hummel’s difficult concerto with a strength and softness, skill, precision and rounding which astonished everyone, and which without doubt even the master, who, removed from every ignoble consideration, has been a true friend of the artist since his sojourns in Petersburg, if he had been present would certainly have appreciated it in full fairness.”[58] The Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung pronounced its judgement: “Here, as elsewhere, Mad. Szymanowska found enthusiastic admirers, who in all respects rated her playing far above the playing of many famous artists and seemingly found in it the pinnacle of what it is possible for human strength to achieve.”[59]

Chancellor von Müller reported on a subsequent dinner at Goethe’s, at which he delivered a rapturous laudation to Szymanowska: “Do we not all feel refreshed, improved, expanded in the core of our being by this gracious, noble apparition which now intends to leave us again? No, she cannot disappear, she has transitioned into our inner being, she continues to live in us with us and even if she starts, as she intends to, to escape me, I will always hold her tight within me.”[60] It is possible that the fourteen-year-old Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy was at the concert because during this time he was a guest at Goethe’s and at the Weimarer Hof yet again as a kind of child prodigy. This comes from the music commentator and Mendelssohn biographer August Reissmann ascribing a quote to the “boy wonder” in which he cheekily commented on Goethe’s oft repeated comparison between Hummel, who briefly was Mendelssohn’s teacher, and the “piano virtuoso Szymanowska, who was staying in Weimar during that time: “Szymanowska is placed above Hummel. They have confused her pretty face with her playing.”[61]

Szymanowska’s departure from Weimar the next day once again threw Goethe into emotional turmoil and invoked the previous separation from Ulrike von Levetzow again. Chancellor von Müller reported: “When I came to see Goethe in the afternoon, I found him still sitting at the table with Mad. Szymanowska; she had just handed out the most delicate little leaving presents, some of them made by her own hand, to the whole family right down to little Wolf, her favourite, and the old gentleman was in the most wonderful mood. He wanted to be cheerful and humorous, but the deepest sorrow of parting was clearly visible. – […] She was summoned to a farewell audience with the Grand Duchess at 5 o’clock, where she appeared dressed all in black in line with court mourning, which heightened the impression for Goethe. The carriage drove up and without him noticing, she disappeared. It seemed doubtful whether she would ever come again. – Then the human in Goethe emerged quite bare and exposed; he asked me most urgently to make sure that she should come back and not leave without a goodbye. A few hours later, the son and I drove her and her sister to him. – ‘I part from you bountiful and comforted […] You have validated my self-belief, I feel better and more worthy because you respect me. Speak not of parting, nor of thanks; let us dream of our reunion’ […] … every effort at humour did not help [Goethe] to hold back the tears that broke free, speechless he enfolded her and her sister in his arms and his gaze stayed with them for a long time as they disappeared through the long open row of chambers. – ‘I have a lot to thank this wonderful woman for’, he told me later, her friendship and her wonderful talent have given me back to myself.”[62]

Szymanowska’s concerts in Weimar and in Goethe’s house were the subject of discussion for a long time and the pianist and the poet remained in contact over the years, even if only by letter. In December 1823, in a letter to the painting collector Sulpiz Boisserée from Cologne, who also wrote about art and architecture, Goethe looked back on Szymanowska’s visit to Weimar: “At the same time, Count Reinhard and his family arrived at our house, his birthday was celebrated cheerfully and respectably […] An incomparable pianist, Madame Szymanowska, whose charming presence and inestimable talent had already brought much joy to me in Marienbad, came directly after them, and for two weeks my house was the meeting place for all music friends lured by high art and amiable character. Court and town, excited by her, lived henceforth in sounds and pleasures. – Directly after her, the minister of State von Humboldt, one of the true old friends from the Schiller period, visited me …”[63]

On 14 February the following year, Goethe noted: “After dinner, Chancellor von Müller, bringing news of Madame Szymanowska, also talking through other politics”[64], on 27 March: “News of Madame Szymanowska in Constitutionnel“,[65] a Parisian newspaper for business, politics and literature. In a letter from London dated 2 July 1824, Szymanowska expressed her disappointment that Goethe – as she had learnt from Chancellor von Müller – did not intend to visit Marienbad in this year. She was happy with her stay in London. On her return to Poland, she intended to have a stopover in Weimar.[66] In June1829, Szymanowska had Zelter announce in a letter that two Poles would be visiting Weimar, the poet Adam Mickiewicz, who would later be her son-in-law, and the lyricist, dramatist and translator Antoni Edward Odyniec: “Our friend Mad. Szymanowska recommends a talented Polish compatriot and poet particularly to you as prince of poets. His name is Mickiewicz and he intends to travel through Germany to Italy. The young man already speaks considerable German and is particularly recommended. The rest you may learn from him directly.”[67] In fact, Mickiewicz and Odyniec arrived in Weimar on 18 August 1829 and stayed there at Goethe’s invitation beyond his birthday and up to the end of the month.[68]

After Szymanowska left Weimar on 5 November 1823[69], she travelled to Halle and then to Dessau, where she gave a concert before the ducal family von Anhalt-Dessau. She then travelled to Berlin again, where she gave concerts on 10 December and on 7 January of the following year. In relation to the first concert that took place in the afternoon and for which entry tickets were sold, The Kurjer Warszawski reported that the Prussian King, accompanied by princes, select personalities and leading artists, had attended the performance. Szymanowska’s pace, rigour and her feeling when playing the pieces by Beethoven, Field and the Prussian Prince Louis Ferdinand were praised by a Berlin reviewer. The pianist had been asked, on her way to Paris, to also perform in Hannover, Braunschweig, Kassel and Frankfurt (PDF 6).[70] The concert on 7 January 1824 was held, as the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung wrote, on the occasion of a “morning entertainment” at which a quintet for wind instruments and piano by Beethoven, a trio for piano, violin and cello by Prince Louis Ferdinand and a “Rondo alla Polacca” by Field were performed “not without applause from the numerous people present”.[71] During her stay in Berlin, Szymanowska corresponded with Chancellor von Müller whom she told about her future travel plans, through whom she sent greetings to Goethe and from whom she requested a letter of recommendation to be sent to Braunschweig. On 1 January, she met Ottilie von Goethe in Berlin.[72]

In actual fact, on her subsequent trip to Paris, Szymanowska did stop in the cities that had been flagged. On 26 January 1824, Goethe noted in his diary: “Letter from Madame Szymanowska from Frankfurt”[73] and on the same day reported to his daughter-in-law Ottilie: “My friend Szymanowska was warmly received in Braunschweig, flew through Hannover, arrived as quick as lightening in Frankfurt where Schlossers were accommodating to her …”[74] As the Kurjer Warszawski reported, after her concerts in Braunschweig and Hannover she received an invitation for a concert trip to London. In Kassel, she met the violinist and composer Ludwig Spohr, who was working there as a conductor and choirmaster and who, like many other famous musicians before him, wrote a “mystery round” composed for her and a dedication in her poetry and scrapbook album.[75]

In March and April 1824, she performed in Paris where she met Prince Radziwill, in London from May to June, in Milan in October, in Florence in November and in Rome, Naples and Venice in the run up to January 1825. From February to September 1825, she gave concerts again in London, then in Paris and Amsterdam until the end of the year. (Fig. 11) In the first half of 1826, she was in London and Paris and then returned to Warsaw. In January and February 1827, she gave farewell concerts in Warsaw and Vilnius, in March and April in Riga and St. Petersburg, before settling with her daughters Helena and Celina in St. Petersburg. In 1828, she embarked on another concert tour to Kiev, Warsaw, Moscow and St. Petersburg, which ended in March of that year.[76]

From that point on, she taught and socialised with a group of friends and acquaintances, which included famous poets and musicians, such as Mickiewicz, Alexander Puschkin, Michael Glinka and John Field. In July 1831, she died after falling victim to a cholera epidemic that had gripped the whole of Europe and Russia.[77] Her compositions kept her memory alive for several years. She has been listed in the leading European music lexica since her death, and still is today.[78] In 1836, the composer Robert Schumann wrote about Szymanowska and the etudes that she had written: “The name will be a wonderful memory for many. We often heard this virtuoso called the female field in which, if these etudes are anything to go by, shows that there is some truth in it. They are delicate blue wings that neither push down nor lift the weighing scale, and which nobody would wish to truly challenge. […] In creation and character, at any rate, we call her the most significant find that the musical world of womankind has delivered to date…”[79]

Axel Feuß, September 2021

Literature:

Doris Bischler: “Ein weiblicher Hummel mit der leichten polnischen Fazilität”. Konzertreisen und kompositorisches Werk der Klaviervirtuosin Maria Agata Szymanowska (1789-1831), zugleich Dissertation Hochschule für Musik Würzburg, Berlin 2017

Maria Stolarzewicz: Goethe’s connections with Maria Szymanowska and her sister Kazimiera Wołowska. Several comments, in: Annales. Académie Polonaise des Sciences à Paris, Volume 16, Paris/Warsaw 2014, pages 115-124

Anna E. Kijas: Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831). A Bio-Bibliography, Lanham/Toronto/Plymouth 2010

Dagmar von Gersdorff: Goethes späte Liebe. Die Geschichte der Ulrike von Levetzow (Insel-Bücherei, 1265), Leipzig 2005

Anne Swartz: Goethe and Szymanowska. The years 1823–1824 in Marienbad and Weimar, in: Germano-Slavica. A Canadian journal of Germanic and Slavic comparative studies, Vol. 4, No. 6 (autumn), Waterloo, Ontario 1984, pages 321–330

Johannes Urzidil: Goethe in Böhmen (1932/1962), Zürich, Munich, third edition 1981

Józef Mirski: Maria Szymanowska 1789-1831. Album. Materiały biograficzne, sztambuchy, wybór kompozycji, Krakau 1953

Maria Iwanejko: Maria Szymanowska, Krakau 1959

Gustav Karpeles: Goethe in Polen. Ein Beitrag zur allgemeinen Literaturgeschichte, Berlin 1890

Gustav von Loeper: Zu Goethes Gedichten “Trilogie der Leidenschaft”, in: Goethe-Jahrbuch, published by Ludwig Geiger, Volume 8, Frankfurt am Main 1887, pages 165-186

Online:

Website of the Maria Szymanowska Society, Paris: http://www.maria-szymanowska.eu/index-de (multiple languages)

Jacqueline Leung: Maria Szymanowska – The Polish Pioneer, in: Revisiting History, Volume 5, spring 2017, on: Piano Performer Magazine (with music example), http://magazine.pianoperformers.org/revisiting-history-maria-szymanowska-the-polish-pioneer/

Maria Stolarzewicz: Goethe’s connections with Maria Szymanowska and her sister Kazimiera Wołowska. Several comments, 2014, http://www.maria-szymanowska.eu/pub/files/Maria_Stolarzewicz.pdf

Danuta Gwizdalanka: Maria Szymanowska, on: MUGi Musik und Gender im Internet (Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg), https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/old/A_lexartikel/lexartikel.php%3Fid=szym1789.html

Jasmin Jablonski: Szymanowska, Maria (Europäische Instrumentalistinnen des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, 2011), on: Sophie Drinker Institut für musikwissenschaftliche Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung, https://www.sophie-drinker-institut.de/szymanowska-maria

Sylwia Zabieglińska: Maria Szymanowska 1789-1831 (English/Polish), on: Dziedzictwo Muzyki Polskiej, https://portalmuzykipolskiej.pl/en/osoba/6777-Maria-Szymanowska

(All links cited here and in the comments were last accessed in September 2021.)