Józef Piłsudski in German prisons

Danzig/Gdańsk, 23rd to 29th July 1917

Józef Piłsudski and his Chief of Staff, Colonel Kazimierz Sosnkowski, were arrested in Warsaw on the morning of 22nd July 1917. At the time Poland's relations with Germany had been poor for some time. The so-called “oath crisis” and the internment of the soldiers from the first and third brigades of the Polish legions had taken place barely two weeks before the arrest. Governor General Hans von Beseler informed the then Provisional Council of State (Tymczasowa Rada Stanu) of the reasons for Pilsudski's arrest. The German leadership had learned of the change in attitude of the Polish Military Organization (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa, “POW”), under Piłsudski's leadership. He had thus become a major threat to peace in the country and to the military security of allied troops fighting on the other side of enemy lines. After the outbreak of the February revolution in Russia it was generally accepted in Germany that this was no longer an opportune moment to create a Polish army. The Eastern Front had ceased to be a potential threat. The rapid end of the war with Russia seemed to be within reach, so that there were no further benefits to be gained from Poland's continued support.

“The situation requires quick action,” Beseler stated, “the immediate neutralization of both persons (Piłsudski and Sosnkowski). (...) In view of this situation, the internment of these persons must be regarded as an enforceable order...”

At the same time arrests of POW members began, and this paralysed the organisation's activities for several months.

Piłsudski and Sosnkowski were first escorted to the Vienna Railway Station (Dworzec Wiedeński) in Warsaw where they were put under a constant guard. The later Marshal of Poland wore a uniform of the Polish legion; Sosnkowski was in plain clothes. Both were placed in a second class compartment. The destination for the transfer was the city of Gdansk, which for reasons unknown was reached by a detour via Poznan. After a brief stop in the capital of Greater Poland, the journey continued. The prisoners arrived in Gdansk on the night of 23rd July where they were sent for remand in the penal prison (the Royal Courthouse Prison in Gdansk) at Schiesstange 12 (today: ul. Kurkowa).

The Polish prison guard on duty at the time, Jan Bastian, recalled that

“the Marshal was polite but silent”, and that the Germans treated him like a “general”.

The prisoners were allowed to keep their clothes and were detained in separate cells on the third floor. Piłsudski was given a comfortable single cell with a window and an iron bed. The second inmate moved into a cell with less comfort.

As General Sosnkowski recalled, “this building was typified by a strong echo, caused by its construction and its building material, probably completely made of bricks, concrete and iron, so that the steps of our little procession sounded absolutely horrible in the silence of the night”. (...) “My cell”, he added, “measured about five paces in length and three paces in width, and since I do not assume that the architect of the honourable institution made any special effort to express his creative imagination in assessing its historical role, I conclude that the description of my cell will probably be a faithful representation of the Commander's cell.”

In view of the position and officer ranks of the detainees the conditions of detention can be described as honourable and adequate. Piłsudski was supplied with newspapers and books. The meals of the two prisoners were provided by the restaurant of the Vanselow Hotel at Heumarkt 3 (today: Targ Sienny). The Commander was even allowed to order wine with his meals.

In all this, it was no coincidence that Piłsudski and Sosnkowski were moved to the front-line city of Gdansk. The courts in the city worked swiftly, were very strict and often imposed death sentences. Had it come to a trial, therefore, the sentence could have been very detrimental to the prisoners. Indeed, an attempt was made to charge Piłsudski for forging documents. Meanwhile the Pole, Alojzy Rapior, secretary and sworn translator at the court martial in Gdansk, had learned of the matter (see: http://www.swzygmunt.knc.pl/MARTYROLOGIUM/POLISHRELIGIOUS/vPOLISH/HTMs/POLISHRELIGIOUSmartyr2263.htm). In the absence of a superior he called Warsaw to inform the POW and other authorities about the transfer of the detainees. It is therefore possible that the interventions that took place after this telephone call prompted the decision to transfer the two detainees to another prison in Germany.

Piłsudski's cell in Gdansk prison still exists. The memorial plaque inspired by the initiative “Nasz Gdańsk" (Our Gdansk) was unveiled on November 11th 2009 at the prison gate in ul. 3 Maja (Street of May 3). However, the cell itself is not open to the public. That said, it can be viewed virtually (see: https://trojmiasto.tv/Cela-Pilsudskiego-326.html).

Berlin-Spandau, 30th July to 6th August 1917

After their brief stay in Gdansk, Piłsudski and Sosnkowski were individually transferred to Berlin, where their paths now diverged for over a year. They were sent to the prison in Wilhelmstrasse in Spandau near Berlin (now a district included in the capital). The prison was built between 1877 and 1881 and during the First World War around 400 inmates were sentenced here by military courts. After the Second World War the Nazi criminal Rudolf Hess served his sentence here and when he died in 1987 the building was demolished.

The conditions in this prison were considerably worse and the regulations much more rigorous than in Gdansk. It was not allowed to bring in food from the city. In the morning, the prisoners were served thin coffee and a slice of black bread, a lousy soup at noon and the morning menu was repeated in the evening. Germany was experiencing food shortages at the time and the “turnip winter” had only ended a few months earlier. Against this background there was no good reason to supply the Polish prisoners with special food despite their high rank. They were also forbidden to read books and daily newspapers, which was a sensitive issue given their monotonous existence. The lights were switched off at 7.30 in the evening (to save energy!), and they were woken at 5.00 in the morning. The hygienic conditions were catastrophic and the cells were full of bugs. Fortunately, their stay in Spandau was short.

Recalling Piłsudski many years later, the prison warden Oskar Kempe said:

“He was a distinguished gentleman! He was proud, he spoke little, he never asked for anything, he never complained about anything, he just came to Oskar Kempe's office from time to time for cigarettes: I no longer know who sent them to him.”

Wesel, 6th to 23rd August 1917

On August 6th, Piłsudski and Sosnkowski were again moved seperately to the fortress in Wesel on the Lower Rhine near the border to Holland. Built around the turn of the 17th to the 18th century, it was one of the largest fortifications in the Rhineland. Today it is used as a cultural centre. Prison conditions were better here. The commander of the fortress even protested on behalf of Piłsudski because he considered it illegal to intern persons who were neither under investigation nor had been sentenced to imprisonment. Years later, in a conversation in Geneva, Piłsudski asked the German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann to send his regards to the commanding officer of the fortress.

Shortly before the two Poles entered the fortress in Wesel, Lieutenant Colonel Nothe, the Chief of Staff to the Warsaw Governor General, made a statement about the reasons for the internment. He wrote:

“(…) the reason for their arrest and internment is that the secret military organization (POW), led by Piłsudski with the aid of Sosnkowski, showed ultranationalist tendencies, and given the circumstances these were also directed against the occupying power.” Furthermore, according to Nothe, “Piłsudski is one of the most important political personalities in Poland, and is regarded by the people as a national hero because he was the founder and leader of the Legions.”

Although both men were not accused of any crime, Nothe ordered Piłsudski to be closely monitored. He warned that he was an adventurous man who was capable of escaping. His blindly devoted aide Sosnkowski must also be held under observation.

Piłsudski stayed for little more than two weeks in Wesel. His premature transfer to Magdeburg is said to have been the work of Poles who were protesting and demanding his release.

Magdeburg, 23rd August 1917 to 8th November 1918

On August 23rd 1917 Piłsudski was moved to Magdeburg and housed in a one-storey wooden house with a small garden. After the destruction of the fortress the city ordered the house to be handed over to Poland, where it was rebuilt in the Belvedere Park in Warsaw. Although it survived the war, it later fell into disrepair.

Conditions here were much better than in the Spandau fortress. Piłsudski moved into the first floor, where he was given two rooms. He quickly established an orderly daily routine, even though he did not have many opportunities to organize his time actively. In a somewhat ironic letter to his family he described his everyday life as follows:

“I get up at 7:30, I have breakfast at 8:00, I go for a walk in the garden at 9:00. I am not bound to any timetable and I am allowed to choose my own time in the fresh air. I usually spend two to two and a half hours outside, so that I am back in my cell after eleven o'clock and read newspapers and books until noon. I don't have many of the latter. At 12.30 pm we have lunch, a relatively lavish one, at least more so than what I got in Warsaw. The most pleasant time follows after lunch: I drink my own tea, which I brew myself. This is the warmest moment in the room (it was December and the cell warmed up only briefly, after which the piercing cold returned], so I start dreaming. With a cigarette and a good tea your thoughts soon meander far and wide. Since such a state is unhealthy if it lasts a long time, I move on to the more serious part of the day: the chess studies that take up a few hours. In the twilight I walk up and down in the room and when the light comes on, I stop chess to read and write. We have dinner at 6:30, and it's not bad. After that, to spare my eyesight, I no longer work, but rather, with various motivations, play innumerable games of patience. I often interrupt this sophisticated activity in order to stretch my legs in the room. At ten o'clock in the evening I go to bed. I fall asleep easily and thus I end my busy working day.”

In 1918, the prisoner was allowed to go into town in the presence of a guard to see a doctor. Piłsudski suffered from heart pain and rheumatism. In his letters he also complained about his poor mental state, a consequence of inaction and isolation. Members of his family were not allowed to visit him because the authorities refused to grant them a travel permit. During his internment Piłsudski heard about the birth of his daughter Wanda: but only after some delay, because the telegram was deliberately withheld from him. He often wrote to the child's mother, his future wife Aleksandra Szczerbińska. After his release it transpired that she had received only a handful of these letters. Moreover, her living conditions were difficult. She worked in the administrative department of a company that dried vegetables and was forced to return to work just a few days after giving birth.

Years later, Aleksandra Piłsudska recalled this time as follows:

“It was extremely difficult to dream of stopping work; the food was terrible: soup, barley and awful bread that you could scarcely swallow. I ate in canteens because cooking at home was impossible due to the lack of fuel. Butter and other fats were rare. There was no flour in the shops either.”

In Magdeburg Piłsudski heard the sad news of the death of his brother Bronisław in Paris - a much-travelled ethonologist who had explored the Far East and previously lived in exile. About this time he began to record his memories of his time as a legionnaire. The first edition of “Moje pierwsze buje” (My First Battles) was published in 1925. When, at the end of August 1918, the German authorities decided to transfer Kazimierz Sosnkowski from the Magdeburg military prison to the fortress, Piłsudski's agonizing loneliness came to an end. The two men now spent their time playing chess, having discussions and taking walks outside the fortress walls.

Sosnkowski remembered: “After lunch we went about our business. The Commander wrote about his memories of the battlefields in the days of the Legion. (...) I must confess, however, that we often indulged in chess, and our passion for this sophisticated pastime sometimes caused a little friction between us.”

Their detention was now more like an internment with comforts. There were many trips into the city for visits to the cathedral, the museum, parks and other places of interest.

Piłsudski was also allowed to order food from the city. The first supplier was the Magdeburger Hof hotel restaurant (Alte Ulrichstrasse 4), and later the Patzenhofer beer restaurant at Bärstrasse 1. The receipts from this period indicate the reason for the change of supplier: the excessive prices at the Magdeburger Hof. It charged the Polish prisoner around 700 Marks a month for vegetable soup with meat and an evening meal, while the Patzenhofer restaurant only charged 350 Marks. The German government paid 250 marks a month for his meals. The rest was taken over by the General Government in Warsaw, which provided him with three grants of 1,000 marks. Further funds came from Polish party friends, which meant that Piłsudski received a total of ten thousand marks. Despite the Revolution, the balance of 1,445 marks was later met by the German state.

The release from prison

Piłsudski's stay in Magdeburg may have been stressful and arduous, but politically it was a success. Isolated behind fortress walls, the leader was considered a victim of German persecution and gradually became a symbol of the struggle against the occupying forces. In addition, Piłsudski was spared the need to vote for one of the two parties to the conflict in Poland. He was not involved in any political disputes and did not have to commit himself to the Regency Council, the highest body in the Kingdom of Poland, formed by the occupying powers in September 1917, or to the Polish Wehrmacht (Polska Siła Zbrojna). After his arrest, he appealed to the Regency Council to obtain his release, but stressed that this was a purely private matter. The release should be for family reasons.

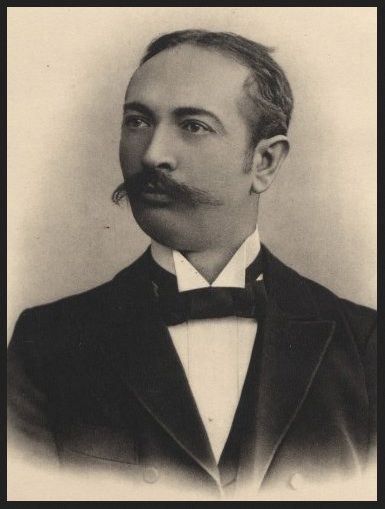

During this time his staff in Poland were organising numerous demonstrations for him. These made him more and more popular, not only as a party leader but also as a leader of the entire Polish people. Since he enjoyed a reputation as an uncompromising fighter for independence his chances of reaching the highest office in the state increased significantly after his return from Magdeburg to Warsaw.

The circumstances surrounding the release of Piłsudski and Sosnkowski are well known. I will therefore only reiterate the most important facts. In view of the catastrophic situation in Germany during the war, Berlin recalled Piłsudski anew. Chancellor Prince Max of Baden sent Harry von Kessler, an officer of the Prussian cavalry to Magdebrug to deliver a food package to Piłsudski, whom he had previously met near Koszyszcze in Volhynia in the late autumn of 1915. The official reason for his visit, however, was to exchange memories from the trenches. The envoy from Berlin delivered a letter from the Chief of Staff on the Eastern Front, General Hoffmann, offering to release Piłsudski in exchange for assurances not to agitate against Germany. The offer was rejected because Piłsudski knew that time was now on his side.

Despite Piłsudski's refusal to comply, the decision to release him and Sosnkowski from prison was made at the beginning of the Revolution, which had broken out in Berlin on the night of November 7th to 8th. On November 8th Count Kessler showed up again in the prison to pick up the two prisoners and take them to Berlin as quickly as possible.

Meanwhile the revolution was also raging in Magdeburg and communications with other parts of Germany were in danger of being severed. Everything happened in a rush. The two Poles only had time to take what they needed. Their remaining belongings were later to be forwarded to them (the manuscript of the book “My First Battles” did not reach Piłsudski until 1924). The liberated prisoners and Count Kessler were picked up in a car by Major Paul van Gülpen, then head of transport. In his report on the event published in 1936, van Gülpen presumably concealed the role of Kessler, because Kessler was no longer welcome in the Third Reich after his exile in 1933 or because he wanted to emphasize his own contribution in releasing the leading icon of the neighbouring country.

It was difficult for anyone to get into the fortress, and here a resolute and courageous female stenographer accompanying van Gülpen, proved to be extremely helpful.

“The streets were full of angry crowds”, recalled van Gülpen. “The stenographer, who tried to lead the vehicle over the river bridge to the citadel, pressed a few pieces of cloth to the car and screamed as if her skin had been burnt off: Move over, move over! We're on our way to the citadel to free political prisoners!”

After meticulous preparation, van Gülpen received permission from the military authorities to travel by car from Magdeburg to Berlin (no train journey was possible because of the revolution). He had spare wheels and firearms with him in his Audi, and the spare wheels in particular were to prove their worth. Travellers often had to stop and change their “war wheels” because they were so poor in quality. Van Gülpen recalled the episode as follows:

“During the journey Piłsudski was given the chance of discovering the glamour and misery of being a motorist. At the time pneumatic tyres were only available as surrogates in Germany, and tyres were said to be filled with a mush of rotten potatoes. As long as they didn't heat up it was very comfortable, but as soon as your speed exceeded 40 km/h, the heat swelled the mash, causing the tyres to burst. The car immediately came to a halt, leaving stinking potato pancakes lying around in the road over the last twenty metres. When such an accident happened in the middle of a village, dogs would run out from all directions and throw themselves on the burnt potato remains, before uttering howls of pain and running away with burnt mouths.”

On the way the travellers had a morning break in the small town of Genthin, before arriving in Berlin on the evening of 8th November where they made a brief stop at van Gülpen's apartment at Reichstrasse 9 for cognac and an entry in the guest book. Here the etiquette of the aristocratic pre-revolutionary world, in which officers, even among enemies, were initially gentlemen, still applied. The former prisoners then moved into an apartment on the first floor of the luxurious Hotel Continental in Neustädtische Kirchstrasse.

At the heart of the revolution

The next day, in the early hours of 9th November, the Poles decided to go into the city. Piłsudski had no sword, but because he was in uniform he was reluctant to take to the streets without a weapon. Count Kessler came to his aid. It took several hours to solve the problem. Because all the weapon depots were closed he gave him his own bayonet. Sosnkowski stated: “Even in the legions, the bayonet was an everyday weapon worn in battle.” Piłsudski and Sosnkowski strolled through the centre of the German capital from Friedrichstrasse to Leipziger Strasse, then to Pariser Platz and Unter den Linden, the city's well-known major traffic axis. Since they had accepted an invitation for a late breakfast, they stopped at the Hiller Unter den Linden restaurant. It was time to switch to business matters, something which the German side probably also wanted, since representatives from the German Foreign Ministry were expecting them there. Sosnkowski called this meeting the “feast of the plague victims”:

“(...) Breakfast was served in a small separate room”, he recalled, “which was not on the street but at the back of the restaurant. A line of minions in flawless tailcoats, a splendidly laid table, the snow-white tablecloth, flowers, the shining silver, the shining crystal glass and the lush gilding of the old German style were all flooded by the electric light that fell from the chandeliers. The outside blinds on the hall windows were tightly closed. Prince Hatzfeld, Count Kessler, van Gülpen and I were in plain clothes, only the Commander was in his humble, worn uniform, whose grey colour made a strange contrast to the overall picture.”

During the meal the Germans tried again to get Piłsudski to pledge not to do anything against Germany, but he again explicitly refused. In view of the current political situation the Germans were aware that they had neither leverage nor incentives. That said, it was vital to ensure an orderly passage through these areas for the German troops that were to be quickly withdrawn from the East. But now it had become pointless to continue negotiations, especially since those present could hear shouting in the streets. The revolution in Berlin was in full swing. The breakfasters then made a hasty departure from the Hiller Restaurant without a declaration from the Poles. The revolution and the abdication of the German Emperor Wilhelm II accelerated further developments. Count Kessler appealed to his superiors to arrange for Piłsudski to leave the city immediately:

“(...) It was clear that it was high time to get Piłsudski out of Berlin (the Maikäfer barracks had already been stormed)”, Count Kessler wrote in the “Frankfurter Zeitung” of 7th October 1928, “so I went with [Hermann] Hatzfeld to the War Ministry to demand a chartered train. We were welcomed by a Major of the General Staff, who, as in the best days of the war, was distracted and ironical. To him Piłsudski was still a very ordinary scoundrel (...)”

The return to Warsaw

On the evening of November 9th, accompanied only by Paul van Gülpen, Piłsudski and Sosnkowski left Berlin on a short train - it only had one wagon - from the station at Friedrichstrasse, which was located near the Hotel Continental. Some sources erroneously state that Count Kessler was also present. But he bade farewell to the Poles in the hotel and remained in the German capital for several more days. During the journey Piłsudski and van Gülpen enjoyed a number of relaxed conversations about the former's relationship with Germany and German-Polish relations (Piłsudski spoke German well, but is said to have had a strong Polish accent).

“The long trip to Warsaw and the situation we found ourselves in gave me the opportunity to talk about topical issues in a way that was more open than would normally have been the case. In our conversations I was able to convince myself that Piłsudski's attitude to us was basically friendly and deeply genuine. He repeatedly said that he had enjoyed fighting alongside the Germans, since we were always loyal neighbours and reliable comrades in arms. So why should two new nations not now be able to embark on a peaceful policy? Since each is dependent on the other it will be possible to come to an understanding with good will.”

In Thorn the German Revolution caught up with the travellers once again. The Soldiers and Workers Council had taken over command of the station. The train was stopped and the roles now changed. This time Piłsudski had to take over the responsibility for protecting van Gülpen.

In the morning hours of November 10th the train entered the Vienna station in Warsaw, to be welcomed by a small group of people, including Prince Zdzisław Lubomirski and a few POW officials. After breakfast some personal items had to be obtained quickly since the two returnees did not even have a change of clothes. After a short break Piłsudski turned to the gathered crowd who had already learnt of his arrival. His speech was neither long nor rousing, but gave him the opportunity to proclaim his will to fight and his ethos to his compatriots:

“Citizens! Warsaw welcomes me for the third time. I believe that we shall see each other many times under happier circumstances. I have always and will always continue to serve my homeland and the Polish people with my life and blood. I can only greet you briefly, since I have a cold. I have a sore throat and chest pains.”

He was not able to see Aleksandra Szczerbińska and his daughter Wanda until the afternoon. After that, events moved quickly. On 11th November Józef Piłsudski took over the leadership of the Polish military high command from the Regency Council. The next day he issued a statement that the Council had requested him to form a national government.

Van Gülpen stayed in a private residence in Warsaw for two days. Before leaving for Berlin, he received a photo with a personal dedication from Piłsudski On his return journey a special compartment was placed at his disposal, reserved “for the government only”. Shortly afterwards Count Kessler was appointed German envoy to Poland. He stayed in Warsaw from 20th November to 15th December 1918, where, amongst others, his portfolio included the solution of all problems relating to the repatriation of German troops.

A few months later, in March 1919, Józef Piłsudski gave an interview to the French newspaper “Le Petit Parisien” in which he left no doubt as to what he thought about the German diplomat Count Kessler and his share in his liberation from prison. For Piłsudski it was – not without reason – simply a part of a political game:

“I knew him personally and was involved with him during the war as leader of the Legions”, said Piłsudski. “He knew the revolutionaries would set me free. He wanted to give me the impression that he had freed me, and no doubt imagined that he would harm me in the eyes of the coalition, whereas the two years of imprisonment in Germany would be forgotten.”

Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, June 2018

The quotations come from:

P. van Gülpen, Moje Spotkanie z Piłsudskim (My Meeting with Piłsudski), in: “Niepodległość”, vol. 14 (July–December 1936), pp. 441–447;

Interview in “Le Petit Parisien” (16.03.1919), [in:] Józef Piłsudski, Pisma zbiorowe (Collected Writings), vol. 5, Warsaw 1937, p. 66;

Wacław Lipiński, Uwolnienie Józefa Piłsudskiego z Magdeburga według relacji hr. Harry Kesslera (The Liberation of Józef Piłsudski from Magdeburg based on the report by Count Harry Kessler), in: “Niepodległość”, vol. 18 (November–December 1938), pp. 462–469;

M. J. Wielopolska, Więzienne drogi Komendanta. Gdańsk-Szpandawa-Wesel-Magdeburg (The Commander's Prison Journeys, Danzig-Spandau-Wesel-Magdeburg), Krakau 1939;

Aleksandra Piłsudska, Wspomnienia (Memoirs), London 1960;

Wacław Jędrzejewicz, Kronika życia Józefa Piłsudskiego 1867-1935 (The Life of Józef Piłsudski 1867-1935), vol. 1: 1867–1920, London 1977.

Exhibition:

The exhibition in “Ravelin 2” shows the history of the fortress and the citadel of Magdeburg. Also exhibited is a miniature replica of the wooden house in which Piłsudski was imprisoned.

The President of the Federal Republic of Germany Frank-Walter Steinmeier in Warsaw (german):

http://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Reden/DE/Frank-Walter-Steinmeier/Reden/2018/06/180605-Polen-Warschau-Konferenz.html

![Flyer to protest against the illegal internment of Piłsudski, 1917 Flyer to protest against the illegal internment of Piłsudski, 1917 - Flyer: On Sunday 29th of this month we will gather in front of the Adam Mickiewicz Monument at 11 am to protest against the illegal internment of Commander Józef Piłsudski and Chief of Staff of the First Brigade, Lieutenant Colonel [Kazimierz]. Sosnkowski](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/obywatele-obywatelki-inc-dnia-29-bm-w-niedziele-zbieramy-sie-o-godz-11-rano-na-0_kopie.jpg?itok=hxoxe_Lq)