Flexible in all systems. The many lives of Konrad Gruda

Origins and youth

Konrad Gruda was born Konrad Glücksmann on 25 October 1915 in Bielsko (Bielitz), which at that time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He came from a prominent Jewish family.

His father Siegmund/Zygmunt Glücksmann (1884–1942), the son of a kosher butcher from near Wadowice, was a lawyer and a leading activist in the Jewish Social Democrat movement in Galicia, and later among the German Social Democrats in the state of Poland. After being wounded in the First World War, he founded a legal chambers in Bielsko, joined the local council and was considered a Marxist. For two legislative periods, he served as a representative in the Silesian state parliament, opposed the voivode Michał Grażyński and issued early warnings about the National Socialists[1]. He fled from Hitler, travelling with his family to Lwów (Lviv/Lemberg), which had by then been incorporated into the Soviet Union. From there, he was deported by Stalin to Siberia in the autumn of 1940. After his release following the Sikorski-Mayski agreement of 1941, he moved to Bukhara in Uzbekistan. There, he worked in the repatriation centre for Polish soldiers, where he became infected with typhus and died[2].

Konrad’s mother Hilda, née Rosner (1888–1972) also came from a Jewish family from Bielsko. Her father Salomon (1851–1940) was a travelling salesman. Her brother Rudolf (1887–1955) became a dermatologist in Vienna after studying medicine there. He survived the Holocaust after going into hiding in Klosterneuburg[3]. Hilda’s parents sent her to Britain for two years to study. Afterwards, she worked as a teacher and later accompanied her husband to the Soviet Union. After 1945, she taught English for several years at what was now the Polish university in Wrocław. She later moved to Sweden together with the family of her daughter Ruth, born in 1926, who was married to Jerzy Kobryński (1921–1998), and who worked occasionally as a dentist. She remained there until the end of her life. During the 1950s, Kobryński taught espionage techniques at the training centre of the Ministry for Public Security (Ministerstwo Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego) in Legionowo[4].

Konrad attended the grammar school in Bielsko, passing his higher school-leaving exams in 1933. He was an active member of the Jewish sports clubs in the town, particularly as a swimmer. Even at an early age, he went on hikes and skied in the Beskid mountains nearby. In 1930, he met Fritz Kantor (1908–1979) at an international water polo competition in Prague, where he was taking part with his club from Bielsko. Kantor was a successful player in the Hagibor Prague Jewish sports association. It emerged that Kantor had found a way of combining his two passions, sport and literature, in his line of work. He had already become one of the best-known young writers of the time under the pseudonym Friedrich Torberg. Glücksmann was keen to follow his example. He was particularly impressed by Torberg’s book “Die Mannschaft. Roman eines Sportlebens” (“The Team. A Sports Novel”), published in 1935[5].

However, at the insistence of his parents, he first studied law at Jagiellonian University in Kraków. During this period, he joined the Association of Independent Socialist Youth (Związek Niezależnej Młodzieży Socjalistycznej), remaining a member until the organisation was disbanded in 1938. It is said that due to his political activity, he was brought before a court in Kraków in 1937 and sentenced to two years in prison on parole[6]. In any case, he abandoned his studies at this point in time. In 1938/39, he took on a part-time job in the office of the Śląski Zakład Kredytowy bank in Bielsko.

The war years

After the outbreak of war in 1939, he fled to Soviet-occupied Lwów (Lviv/Lemberg), where he began studying at the Institute of Soviet Trade, the former Polish Foreign Trade Academy[7]. According to his own account, however, he studied music together with his friend Jerzy Berent (1917–2003), since this was the least political of all subjects[8]. Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, he joined the Red Army and until 1942 fought as a mercenary on the north-western section of the front. There, his main task was to ensure that the radio communications technology was functioning properly. After he was wounded in March 1942, he was sent to the Russian city of Voronezh to recuperate. He then worked as an overseer in a sawmill in Novosibirsk for several months.

From April 1943, he signed up as a volunteer with the Tadeusz Kościuszko First Infantry Division (“Berling Army”) after it was established, where he was evidently highly regarded as a “capital fellow” due to his high-level skills[9]. In October 1943, according to his own account, he took part in the battle of Lenino[10]. Initially, he belonged to the Sielce Third Infantry Regiment (May to August 1943), then joined the Smoleńszczyzna Second Infantry Regiment (July 1943 to March 1944). In each case, he was responsible for political propaganda campaigns.

In 1944, he returned to Poland with the Red Army. According to his own account, he became the head of the Bureau for Culture and Public Relations in Lublin. There, he founded the “Gazeta Lubelska” newspaper and made himself editor-in-chief[11]. In fact, under the name of Konrad Gliksman, he was a member of an army operations group headed by the later Party leader Edward Ochab, whose task it was to implement the goals of the communist July Manifesto (Manifest lipcowy) in Lublin and later in Otwock, and to create structures that would later evolve into the citizens’ militia (Milicja Obywatelska).[12] This related mainly to political-educational training work, which was designed to be explicitly distinct from the model used for the police force during the inter-war years[13]. From September 1944, Glücksmann was assigned to the artists’ group of the citizens’ militia. However, Gruda, who likely assumed his new surname in 1945, was not a member of the Communist Party; rather, he had joined the PPS socialists in 1933 as an act of defiance against his father, whom he resented[14]. In 1948, following the merger of the communist and socialist parties, he became a member of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR).

Career under the communist regime. Rise and fall

In mid-May 1945, Gruda was made voivode commander of the citizens’ militia of Kraków[15]. He remained in this role, at the same rank as a captain[16], until 1946, when proceedings were opened against him due to “permitting an abuse of power”[17]. At the request of the association of invalids, and without having a legal basis for doing so, he had withdrawn ownership of a kiosk from a woman suspected of having appropriated the shop illegally. The lawsuit was crushed. Further investigations followed into the alleged unauthorised assumption and abuse of authority. It was claimed that within a short period of time, he had written off several cars and made money off formerly Jewish property that now belonged to the state[18]. As a result, from 5 November 1946, Gruda was given a new post as commander of the citizens’ militia in Otwock, in the Warsaw voivodeship[19]. In Kraków, he witnessed the pogrom against the Jews on 11 August 1945[20]. The anti-communist resistance was unsure what his position on the matter was. On the one hand, he had given the order to arrest Jews who were attempting to flee. On the other hand, he ordered the arrest of provocateurs and criminals[21]. He later gave witness statements at the trial against those involved in the pogrom. That same year, he married Zofia Winnicka-Bieżeńska (b. 1920) from Drohobycz.

In 1946, Gruda received the Golden Cross of Merit[22], among other honours awarded until the end of the 1940s. In Stalinist Poland, he contributed to the creation of a socialist sports movement[23]. In the local assessments of the Freedom and Independence (Wolność i Niezawisłość) underground organisation, which was not exactly well known for being friendly towards the Jews, he was initially rated positively. However, it was soon rumoured that he had received his training at the NKVD espionage school in Moscow[24].

From August 1947 onwards, the special division of the supreme command of the citizens’ militia in Warsaw conducted investigations into Gruda. He was accused of financial misconduct and having a positive attitude towards elements that were hostile towards the system[25].

On 30 July 1949 (backdated to 1 March 1949), Gruda was dismissed from the citizens’ militia and assigned to the reservists[26]. Two years later, presumably following numerous attempts by Gruda to obtain information and requests for rehabilitation, the Ministry for Public Security justified its decision by claiming that while he was “highly skilled”, he had ultimately underperformed and had committed a series of offences for personal gain[27]. Internally, the assessment was more severe: “Inappropriate behaviour towards his subordinates and an immoral lifestyle.”[28] In the report previously presented by the supreme commander of the citizens’ militia, General Józef Konarzewski, to the minister responsible, Stanisław Radkiewicz, Gruda’s transgressions during the four post-war years in Kraków and Otwock were outlined in detail in a 13-point list[29]. Gruda had largely denied the allegations and claimed that others had been responsible for the misdemeanours. However, the authorities were not convinced by his arguments[30].

From 1950 to 1956, he made an apartment that he rented in Warsaw under the codename “Inwalida” available to the state security organs for clandestine meetings and similar activities (właściciel LK)[31]. The historian Ryszard Nazarewicz (1921–2008), who at that time was a major in Division V of the Ministry for State Security (Ministerstwo Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego) had hired him as agent-informator[32]. One of his advocates was the deputy director of Division III, Leon Andrzejewski, whom he knew from the Kościuszko division[33].

A radio and television sports journalist

In September 1949, Gruda joined the state travel company ORBIS, where he remained until 1954. After working briefly for the International Repatriation Committee for Korea, which organised the exchange of prisoners between North and South Korea – he later also became a member of a commission tasked with monitoring the ceasefire in Laos – from April 1954 onwards, he was sent to the sports department at Polskie Radio as the “strong man” successor to Aleksander Rekszta. He remained in a management post there until 1957[34]. One of his inventions was the daily show “Kronika Sportowa”, which was first aired on 30 November 1954 and which is still being broadcast today.

Thanks to his good connections, he was able to improve the funding available for reporting and made it more professional. Ultimately, however, this proved his downfall. When he demanded that employees who in his view were unsuited to their post, he was brought down by the editorial collective and the trade unions, with the agreement of the Communist Party.

During the 1960s, he was an editor and popular presenter for Polish television, where he worked on programmes such as “Medale i detale”, “Na zdrowie” and “Start i meta”. His colleagues were aware of his political past, which meant he was sometimes feared by those who at the same time also acknowledged his outstanding qualifications in the field of sport[35].

In 1949, he became president of the Polish Swimming Federation, and following its disbandment in 1951, chairman of the swimming section on the Main Committee for Physical Culture. He remained in this post until the Polish Swimming Federation was revived in 1957. In this capacity, he also attended the Olympic Games in Helsinki in 1952, and also travelled as a journalist to the Olympic Games in Melbourne in 1956 and Rome in 1960. In 1957 and 1960, he was chairman of the Investment Committee of the Polish Swimming Federation; from 1960 to 1962, he was vice-president for sports and from 1962 to 1965, he was chairman of the Committee for Water Sports. On occasion, he was allowed to travel to France and Britain so that his wife could receive medical treatment.

However, from 1963 to 1967, he was refused permission to travel abroad on direct orders from the Interior Minister, Władysław Wicha[36]. Gruda was clearly shocked and taken by complete surprise by this measure, and attempted to defend his position by writing letters of justification, as well as making efforts to identify the persons responsible[37]. Both strategies proved ineffective.

Gruda was already under suspicion of working as a spy for a western country even during the late 1950s. The security organs began an “operative observation” of Gruda, in other words, a measure in which “so-called target persons [were] kept under observation over a specified period of time in order to gain information about the places they visited, their connections, employment, life habits and, possibly, illegal activities”[38]. Operation Sprawodawca (“reporter”) was conducted from 1961 to 1964[39]. Under the direction of Captain Ryszard Bartosik, Gruda’s environment was thoroughly investigated with the help of informants recruited for the purpose. In one case, an attempt was even made to plant a female informant in the home of Gruda’s invalid mother[40]. The scale of the operation is reflected in the fact that 117 names are listed from his personal and professional environment in the record of the people involved.

Despite this thorough surveillance, which focused on Gruda’s foreign contacts, his interest in an allegedly newly invented combustion engine and the purchase of a western car, no evidence could be found of any kind of spying activity. Gruda’s connections were limited mainly to exiled Poles who had little influence.

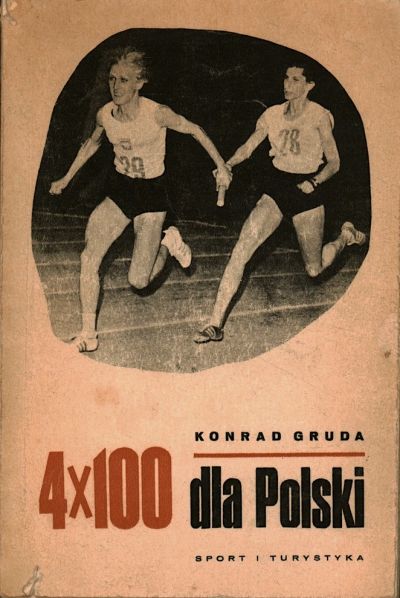

During the 1950s and 1960s, he wrote or edited several books. One which attracted a particularly high level of interest was the story of a flagship in Polish sport, the women’s 4x100 metre athletics team, who won gold at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Gruda was friends with the star of the team, three-time Olympic champion Irena Kirszenstein-Szewińska. He also wrote occasional magazine articles, including for “Przekrój” and “Turystyka”, a monthly periodical for which he was editor-in-chief from 1950–1952[41].

From the late 1950s onwards, Gruda was in casual contact with Hansjakob Stehle from the “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” newspaper (“FAZ”). “The editor spoke very good Polish, but he didn’t know much about sport,” Gruda later wrote. In 1959 and 1960, he wrote several articles for the FAZ about Polish sports under the pseudonym “Karol Wisniewski”[42]. This connection also came to the attention of the state security organs, although piecing together the story of this small-scale collaboration stretched their research capacity to its limits.

Emigration to West Germany and second career in television and as a book author

Following the anti-Semitic campaign of 1967/68, Gruda decided to leave Poland. He himself had been the target of criticism in this regard. He was accused of making euphoric statements about Israel’s military successes in the Six-Day War and of being condescending towards Poland’s “Arab friends”[43]. From February 1969 onwards, he was in effect banned from being shown on screen, which led to his earnings being cut by 60%. At the end of August, he submitted his resignation and applied for permission to emigrate[44]. A short time before that, his daughter Katarzyna had been the target of a campaign by the secret services, following which she and her partner had left the country[45]. At Christmas 1969, Gruda, who officially was travelling to Israel, arrived in Frankfurt/Main together with his wife Zofia. He had been issued a visa for Israel by the Dutch embassy in Warsaw[46]. On Polish television, his emigration was met with a degree of surprise as well as an overinflated understanding of his opportunities in the west[47]. He revived his old journalist contacts, such as with the FAZ sports journalist Karl-Heinz Vogel, who organised a job for him in the sports editorial office for ZDF (German state television broadcaster – translator’s note), which he held from 1 October 1970 until his retirement in June 1978[48]. However, he never appeared on screen. His boss in the “Unter den Eichen” ZDF studios in Wiesbaden was Bruno Moravetz, a winter sports expert from Transylvania[49]. In the years that followed, he also maintained contact with his former Polish colleagues.

During this time, he also continued to write books, beginning with the dystopian novel “Zwölf Uhr einundvierzig. Ein Roman aus dem Jahr 2289” (Twelve forty-one. A novel from 2289), which was published in 1975 in “Jugend und Volk” in Vienna, in the translation by his compatriot from Galicia, Oskar Jan Tauschinski, and which was the subject of a humorous discussion in the FAZ by Tadeusz Nowakowski[50]. In the novel, Gruda describes the dystopia of programmed, controlled beings that live on the ocean floor – he had clearly read Čapek and Verne – whose romantic relationships are generated by computer. One individual rebels against the system. In the end, love wins. In Gruda’s short prose, too, the main area of interest was the important role played by sport and its major influence on life[51].

For about a decade, Gruda also wrote commentaries for the weekend supplement to the “Süddeutsche Zeitung” newspaper (“SZ”), translating satire from the Russian, particularly works by Arkady Inin[52]. He also translated Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s play “Zhyds of St. Petersburg” into German[53]. His text was used as the basis for the first German performance of the play, directed by Gerhard Hess, on 3 December 1995 at the Theater Dortmund.

The later sports books were published by Wilhelm Fischer Verlag in Göttingen. From 1988 onwards, he ran a small publishing house in Wiesbaden, “Stundenglas-Bücher”, together with Karl-Heinz Behrens[54].

Following his arrival in the Federal Republic of Germany, he made attempts to obtain compensation as a subject of racial persecution, contacting the Frankfurt lawyer Natalia Rosenberg asking her to conduct research on the matter on his behalf. However, her enquiries with the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen failed to produce the necessary information[55].

He remained at least a minor subject of interest for the Polish secret service. During the early 1970s, an informant, “Henryk”, alias Bolesław Kierski, was deployed to spy on him – and on the entire circle of Jewish emigrés from Poland in the Federal Republic of Germany[56].

During his later life, Gruda played an active part in the cultural life of Wiesbaden, among other things as a collector of exlibris. He regarded himself as a decades-long member of the SPD, for which he received an honour in 2011[57]. He played an active role in supporting the founding of the Spiegelgasse Active Museum for German-Jewish History (Aktives Museum Spiegelgasse für Deutsch-Jüdische Geschichte), and he was also active in the Wiesbaden section of the German Alpine Club.

His work as a journalist was also the subject of an event held by the Mainz-Wiesbaden German-Polish Society (Deutsch-Polnische Gesellschaft Mainz-Wiesbaden) in 2002. He spent the final years of his life in Wiesbaden, remarried after the death of his wife Zofia, and continued to publish until the end. He died on 11 June 2012 in Wiesbaden. His daughter lives in New York.

Publications:

- (ed.), Przepisy sportowe pływania, skoków do wody i piłki wodnej, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1952. 141 p.

- (ed.), Olimpiada z odniesieniem do domu. Reportaże, Wspomnienia, Opowiadania. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka 1957. 192 p.

- (with Andrzej Roman), Droga do Tokio, Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1965. 224 p.

- 4 x 100 dla Polski, Warszawa: Sport i Turystyka, 1967. 261 p.

- Jej dzień, Warszawa: Twój Styl, 2001. 184 p.

- Der Torjäger, Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1974. 143 p.

- Zwölf Uhr einundvierzig. Ein Roman aus dem Jahr 2289, Wien/ München: Jugend und Volk, 1975. 222 p. (New edition entitled “Zwölf Uhr einundvierzig. Wird Jan der tödlichen Gefahr entrinnen?”, München: Arena 1979).

- Kein Sieg wie jeder andere. Sporterzählungen, Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1979. 239 p.

- (ed.), Spannende Geschichten, Berichte und Erinnerungen aus der Welt des Fußballs / vol. 1. Fußball, das ist ihr Leben! Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1980. 87 p.

- (ed.), Spannende Geschichten, Berichte und Erinnerungen aus der Welt des Fußballs, vol. 2: Tolle Tore, große Stars, Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1980. 96 p.

- (ed.), Deutschland vor, noch ein Tor. Spannende Geschichten, Berichte und Erinnerungen aus der Welt des Fußballs, Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1980. 175 p.

- Mount Everest. Auf Leben und Tod, Göttingen: W. Fischer, 1980. 247 p.

- (ed.), 100 Jahre Sektion Wiesbaden des Deutschen Alpenvereins: [1882–1982]. Festschrift. Wiesbaden: Sektion Wiesbaden des Deutschen Alpenvereins, 1982. 75 p.

- (ed.), Die dritte Halbzeit: 65 Leseabenteuer für Fußballfreunde, Bad Homburg: Limpert, 1985. 222 p.

- (with Hanna Abé, ed.), Das einsame weiße Segel. 35 Lese-Abenteuer für Segelfreunde, Bad Homburg: Limpert, 1985. 234 p.

- Der Slalomhang oder Der Hang zum Slalom, Wiesbaden: Die Stundenglas-Bücher, 1989. 235 p.

- Diese kleine Unsterblichkeit. Szenen einer Show. Roman, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag 1995. 302 p. (pl. “Ta mała nieśmiertelność”, Warszawa: Rytm, 1997. 264 p.).

- Live und andere Erzählungen. Norderstedt: Book on Demand, 2011.

Markus Krzoska, September 2024

![Konrad Gruda: Zwölf Uhr einundvierzig. Wird Jan der tödlichen Gefahr entrinnen?, München 1979 [1975] Konrad Gruda: Zwölf Uhr einundvierzig. Wird Jan der tödlichen Gefahr entrinnen?, München 1979 [1975] - Book cover](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/Konrad%20Gruda_Zwo%CC%88lf%20Uhr%20einundvierzig.%20Wird-Jan-der-to%CC%88dlichen-Gefahr-entrinnen.jpg?itok=z9Cru2Qk)