The estate of Aureli Topolnicki, resident between 1945 and 1951 in the DP camp in Wildflecken (Durzyn)

The estate of Aureli Topolnicki (1907–1988) comprises 147 documents (including some copies), some of them two or three pages long. Most of them date back to the years between 1944 and 1951, and a few from earlier or later. In addition the estate contains 12 official stamps from institutional facilities in the Wildflecken displaced persons (DP) camp at Durzyn[1]. The documents consist of Topolnicki’s official and private correspondence, passes, identity cards (including membership cards), reports, certificates, testimonials, deeds, application forms, and private notes. A huge number of documents in the estate are original: in addition a large part of them are transcripts, translations – some of these are certified – and copies. Most of them deal with Aureli Topolnicki’s private life (his career, education, studies), his work as a teacher and head of the Polish primary school in Wildflecken or as head of the Wildflecken Polish school district. Furthermore many documents provide information on the context of the emigration of Topolnicki’s family to the USA in 1951. The estate also contains documents belonging to his wife, Irma, and their son, Otto. A specific section of the documents comprises reports on the school and cultural life in the DP camp and general details on the work in schools. The collection of documents is linguistically various: 48 documents are written in the English language, 43 in Polish, 27 in German, two in Latin and one each in Dutch and Chinese. Furthermore many documents are bilingual: the estate contains 18 Polish-English documents, two German-English documents, one Polish-Russian, one English-Latin and one German-Czech document. There are even two trilingual documents: one German-Polish-English and one German-Polish-Russian.

In 2014 Frau Barbara Karbarz brought the complete estate back from the USA to Poland when she returned after the death of her husband, Otto Topolnicki. Whilst she was sifting through his possessions before moving she came across a carefully-sorted collection of documents that had been stored away in an album. It only took a few glances to realise that this material had obviously been highly important to her dead husband’s father for they clearly covered a decisive phase in the family’s life. She asked her brother, the art historian Romuald Nowak from Breslau, to find an institution that might be interested in taking over the estate, using it in a sensible way and storing its contents adequately. Romuald Nowak made enquiries with a large number of institutions (scholarly institutes, museums, archives etc), in Poland, but none of these showed any real interest. Finally he heard of a travelling exhibition entitled “Between Uncertainty and Confidence. The Art, Culture and Everyday Life of Polish Displaced Persons in Germany 1945–1955”,[2] which had been conceived and worked out by the LWL Industrial Museum at the Hannover colliery in cooperation with Porta Polonica. As a result Nowak contacted the head of Porta Polonica, Dr. Jacek Barski, who agreed to take over the estate.

Because of its size and diversity the estate of Aureli Topolnicki documenting his time as a displaced person cannot be too highly valued by historical research workers, especially with regard to its importance in describing everyday details and cultural events in the Wildflecken camp in the American occupying zone in Germany. The material allows us to reconstruct the life and experiences of Aureli Topolnicki in the years between the setting up of one of the largest Polish DP camps in Germany at the end of the war and its closure at the beginning of the 1950s. Hence the estate contributes to our understanding of the general living conditions in a major DP camp and the changes that occurred during this period, not forgetting the setting up of the administrative and cultural facilities by the camp’s independent administrative body. But above all, the contents of the estate allow us to use the Wildflecken DP camp as a concrete example of the foundation and development of schools and educational establishments for children, young people and adults. Furthermore the documents make clear the extent to which the desire to emigrate influenced the daily life of people in the camp and the difficult hurdles they had to overcome in order to give their families a new perspective abroad.

That the problem of displaced persons (DPs) was not a side issue in European post-war history is shown by the number of people affected. Immediately after the end of the war there were around 11,000,000 displaced persons from 20 states in the old area of the German Reich. 6,500,000 of these alone were living in the Western occupying zones. Even when most of these were repatriated to their home countries in 1945 – some voluntary and others against their will –there were still around 1,700,000 DPs living in the territory of occupied Germany at the start of 1946.[3] As the Cold War set in, the Western allies started to allow compulsory repatriation to the countries in Eastern Europe, a measure which many DPs vehemently opposed. By 1947 over 700,000 DPs of different nationalities were still stubbornly refusing to leave the Western occupying zones. From now on they were regarded as impossible to repatriate.[4]

Immediately after the end of the war the ca. 11,000,000 DPs on German territory contained around 1,700,000 Poles, of whom 700,000 were living in the Soviet zone from where they could be relatively quickly repatriated to Poland.[5] In the following two years a large majority of Polish DPs were indeed repatriated to Poland. Nonetheless the number of Polish DPs in the Western occupying zones was still around 190,000 in June 1947 (ca. 103,000 in the US zone, 76,000 in the British zone and 10,000 in the French zone).[6] These were mainly people who had categorically rejected a return to Poland on political or ideological grounds, or whose homes in Poland had been annexed to the Soviet Union or the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, and had not yet succeeded in finding a new home in other Western European states or overseas.

Both these reasons applied to Aureli de Sas Topolnicki, who laid great value on his aristocratic roots. Hence it was unheard of for him to be repatriated to Poland with his family. Topolnicki was born on 26. November 1907 in the pretty little village of Obertyn in the district of Horodenka in eastern Galicia that was part of the Austrian-Hungarian Kingdom at the time.[7] When Poland became an independent country once again at the end of the First World War this heterogeneous ethnic, cultural, linguistic and confessional area (it contained Poles, Ruthenians, Ukrainians, Jews, Germans and other smaller minorities) was made part of the Second Polish Republic. The Topolnicki family had its roots here in the Eastern area. True, the documents contain no information about Aureli Topolnicki’s childhood and youth, but he must have taken his A-levels because in 1929 he passed an exam and was awarded a grant from the state to study at a state teachers training college in Nieszawa, where he was awarded a teaching diploma in1932. His best subjects were religion, music and German. After this he worked as a teacher for two years, presumably in Bolechów [8], a small town in the district of Dolina in the County of Stanisławów, around 130 kilometres north-west of Obertyn [9]. Here, on 19 October 1934 he was married to Irma Saling [10] , who was seven years younger. Her name leads us to suspect that she came from a German (or German-speaking) family on her father’s side. This is further strengthened on the one hand by the fact that under Austrian rule many Germans moved to the town of Bolechów and the surrounding regions. On the other hand we know that Irma Saling was baptised on her first birthday, 20 April 1915, in Fleißen (Czech: Plesná), a town in the district of Eger (Cheb) in the Sudetenland whose majority population was German, but which ws a part of Czechoslovakia from 1918 until the Munich Agreement made on 29. September 1938. By contrast Irma’s mother, Tekla Łatyk, came from a Polish family [11]. On the 26. August 1935 Aureli Topolnicki swore an official oath of service and on 1. September 1935 he became a temporary teacher in the state secondary school – it had three age groups – in Raków in the district of Dolina [12]. In December 1937 he passed the practical teaching examination with a final grade of “good”, and was henceforth qualified to teach in state schools [13]. As a result Topolnicki applied to be transferred to another school and on 1. September 1938 he took up a post at the boys’ school in Bolechów [14].

Shortly before this his son Otto was born on 20. May 1938 [15]. He was to remain the sole child in the family. Aureli, Irma and Otto were living in Bolechów when the war broke out. After the division of the Polish state by the Germans and the Russians as a result of the so-called Hitler-Stalin pact , the Polish territories east of the Rivers Narew, Vistula and San passed into the hands of the Soviet Union. On 22. June 1941 the German army invaded the Soviet Union as part of Operation Barbarossa, and took the area of Galicia into the General Government. During this time Topolnicki had continually worked at the state school in Bolechów [16]. Around three months after the German army invaded the Soviet Union he was appointed as the headmaster of the state school in Bolechów by the chief of the district of Kałusz His knowledge of German, and possibly the fact that his wife came from a German family, presumably proved an advantage here [17]. According to family relations Topolnicki’s family left Bolechów for Lower Austria (Southern Moravia) sometime between summer and autumn 1943 because they were afraid of the approaching Red Army [18]. However, from the documents in Topolnicki’s estate it is unclear whether all three members of the family left Bolechów at the same time and for the same destination. A handwritten note tells us of a departure from Kraków on 17. September 1943 and an arrival three days later in the Lower Austrian town of Retz. However it seems that Topolnicki did not arrive in the south Moravian town of Lundenburg, around 100 kilometres east of Retz, until September 1944 [19]. On the other hand his identity card issued in December 1945 in Wildflecken-Durzyn notes that the “civilian [was] deported to Germany” [20](Lundenburg) on 16. July 1943. Equally the identity card issued to Irma Topolnicka by the municipal authority in Wildflecken-Durzyn says that she was deported to Lundenburg on 15. August 1944 [21].

The application forms for this identity card give five possible reasons for wishing to remain in Germany: 1. Political prisoner, 2. Prisoner, 3. Prisoner in a concentration camp, 4. Prisoner-of-War and 5. Deported to Germany as a civilian (this could also mean as a forced labourer, amongst others). These reasons were very important because the status of a Displaced Person and accommodation in a DP camp depended on them: not to speak of the later possibility of emigration, for example to the United States. From statements given by members of the family and the fact that Aureli Topolnicki was appointed to the post of headmaster by the German occupying powers in West Ukraine as early as September 1941, it seems highly improbably that the family were deported as forced labourers, whether in 1943 or 1944. Furthermore salary advances given in September and October 1944 by the “Alois Gasser Wholesale Iron and Locksmiths Tools” company in Retz/Lower Danube, prove that Topolnicki was indeed living and working in Retz at the time, and did not [22] travel to (or was deported to) Lundenburg in 1943, as noted in the above-mentioned identity card. In addition, Aureli Topolnicki had his teaching diploma, his certificate of appointment as a state school teacher and the report on his course of practical training as a teacher translated in Vienna in September 1944 [23], something which also shows that his everyday life in Lower Austria was subject to restrictions. Quite the opposite, he clearly hoped to be engaged in the profession for which he had trained.

On the 4. April 1945 Aureli Topolnicki – presumably with his wife and son – set off for Fleißen in the Sudetenland, where his wife had been baptised in 1915 and where she probably had relatives. The family remained there until the end of July 1945, when the campaign to expel Sudeten Germans was in full swing [24]. As a result they fled via Pilsen, Nuremberg and Bamberg to Eichstätt, where they arrived on 30. July [25]. Immediately after their arrival Aureli Topolnicki was appointed head of the school in the Eichstätt DP camp [26]. But the family left the camp once more [27] as early as 16. August for Wildflecken in Northern Bavaria, where one of the largest DP camps in the American occupying zone (indeed in the whole of Germany) was situated on site of the Rhön barracks. More importantly it’s population was mostly Polish. Two days after their arrival, on 4. July 1945, Topolnicki took up work as a secondary school teacher in Wildflecken-Durzyn [28]. The school initially comprised four age groups and 200 pupils, but this quickly rose to over 20 classes with around 800 pupils. This figure did not change greatly, despite the immensely high fluctuation in the number of teachers and pupils on the grounds of repatriation to Poland, the closure of small DP camps and the transfer of the inhabitants to larger camps like Wildflecken. That said, the amount of arrivals and departures gradually declined from 1947 onwards [29].

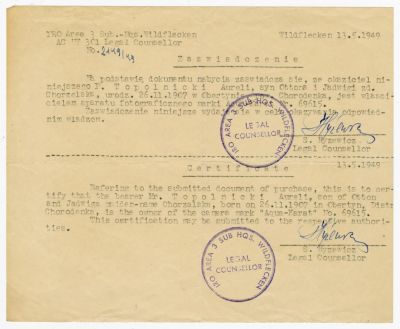

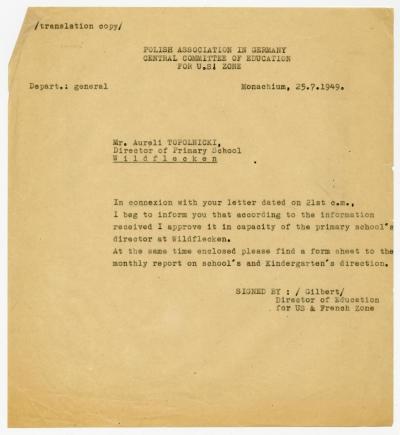

On 5. March 1947 the Central Committee for Schools and Educational Affairs of the League of Poles in Germany (HQ in Munich) appointed Topolnicki as head of the Polish schools in Wildflecken-Durzyn and the surrounding district [30]. He took up the post only a few weeks later, only to break it off once again when he emigrated to Belgium on 16. June 1947 [31]. This second attempt to leave the country – Topolnicki had already worked for a short period in the Netherlands in June 1946 [32] – ended after only a few weeks when he returned to Wildflecken in August 1947[33]. On 29. August he was reappointed as a secondary school teacher there [34]. It is highly probable that Topolnicki became the head of the school in the second half of 1949 [35]. Whatever the case, at the end of 1949, in his function as headmaster, he received a letter from the International Refugee Organization (IRO) [36] telling him that the school would be closed at the end of the year at the same time as the Wildflecken-Durzyn DP camp [37]. Despite protests and the postponement of the closure, the school closed for good in April 1950 at the end of the school year [38].

Alongside his teaching duties Topolnicki was also active in other areas of camp life – amongst others he was a passionate musician and music teacher [39]. Furthermore he was an active member in numerous Polish organisations and societies in Germany. He was a member of the League of Poles in the US zone in Germany and at the same time chair of the Polish committee of the League in Wildflecken [40], a member of the Association of Polish Teachers in Exile [41] and of the Headquarters of the Polish School System in Germany [42]. In addition he and his wife were members of the Polish National Fund [43].

Topolnicki’s wife, Irma, had several jobs during their time in the DP camp in Wildflecken-Durzyn. In December 1945 she took over the administration of the canteen [44], between January 1946 and September 1947 she was a block keeper [45], from June until October 1949 she was employed as a secretary in the IRO registration office, and she was a secondary school teacher between November 1949 and April 1950 [46]. In this connection the school’s headmaster, Aureli Topolnicki, had to deal with accusations of nepotism from the staff, but these were never officially investigated [47]. In addition, between January and June 1947, Irma Topolnicka enrolled in a dressmaking course at the Women’s Professional School in Wildflecken-Durzyn [48]. Their son, Otto, attended the local secondary school between 1945 and 1950 [49]. Until then the Topolnicki family had still not succeeded in emigrating. After their failed attempts to emigrate to the Netherlands and Belgium they made a definite decision to try to emigrate to the United States. Topolnicki seems to have been perfectly clear that he had no real chance of getting a job as a teacher because of his insufficient knowledge of English, the more so because he was already 40. Since he was also interested in natural science and technology [50] he embarked on a course of electronics [51]. But over and beyond this, the Topolnickis continually tried to provide the immigration authorities in the USA with good arguments in order to be able to emigrate as quickly as possible. Thus, in March 1950, Aureli Topolnicki, persuaded the pastor of the Polish community in Wildflecken-Durzyn, Marian Świtka, to issue him with a certificate attesting that he was a “good Pole and Catholic” as well as being “industrious and of exemplary behaviour” [52]. Irma had been given a similar certificate in English and Polish two and a half years previously [53]. In addition the IRO issued Topolnicki with a report on the skills and achievements of local staff – here he was assessed as teacher – which evaluated factors like physical suitability, knowledge and skills, initiative, achievement, reliability etc. [54]

Even when it is impossible to say exactly when Aureli Topolnicki applied for emigration to the USA [55], it seems that, despite all their efforts, the family had to wait for quite some time for a positive answer. In February 1950 Topolnicki stated on a staff form issued by the Resettlement Centre in Schweinfurt) that he had a “sponsor” [56] (and destination) in the form of a certain Karolina Talaga, who was clearly a representative of the American Committee for the Resettlement of Polish DPs [57] On 24. March 1950 the said committee sent him the news [58] that they had confirmed the sponsorship and that they would forward the information to representatives of the committee in Germany [59]. On 19. May 1950 the Displaced Persons Commission in Frankfurt informed Topolnicki that he fulfilled all the preconditions and would be able to travel with his family to the USA in the next few months. It also asked him to ask his “sponsor” to take the necessary action. Interestingly enough, the man named in this document as the sponsor is now a certain William E. McGuirk from East Islip in New York State [60]. A few weeks later Ludwika and Elwira Saling, relatives of Topolnicki’s wife Irma, who had already emigrated to the USA, requested the Congress of American Polonia to intervene in trying to speed up the emigration of Aureli, Irma and Otto Topolnicki, since this was still being delayed. At the end of August 1950 the Congress sent some forms to Aureli Topolnicki, requesting him to fill them out and return them so that they could take action [61]. In mid-November 1950 the American General Consulate in Munich instructed Topolnicki to register [62], three weeks after he had been sent back from Schweinfurt to Wildflecken on the grounds of not having the correct sponsorship documents [63]. Finally, in February, the family moved back to the immigration centre in Schweinfurt, where Aureli and Irma were vaccinated against smallpox [64] and took part in an orientation programme [65]. This time their stay in Schweinfurt proved relatively short as witnessed by the fact that Aureli Topolnicki only had five hours of English lessons and attended one preparation film [66]. On 13. March 1951 the Topolnicki family set out from Bremerhaven for New York on a new chapter in their lives – on the freighter “Gen. Muir” [67].

On their arrival in the USA Aureli Topolnicki immediately began to look for work. He had several jobs in the 1950s [68], and in 1953/1954 he took a training course in technical drawing at the Laski Institute of Technology in Chicago [69]. His son Otto became a citizen of the USA in 1958 at the age of 20; two years later he did his national service at the air force base in New York [70]. He was already married by the time he was given American citizenship and his son Adam Aurelius was born in December that year, to be followed by two daughters, Evelyn, in 1961 and Teresa in 1962 [71]. Aureli and Irma Topolnicki worked hard and managed to achieve a reasonable standard of living. They visited Poland on two occasions, but never set eyes on the regions where they were born, and that had now been lost. The couple spent the final years of their lives in San Diego/California, where they were in charge of a small old people’s home. Aureli Topolnicki died in 1988, to be followed two years later by his wife, Irma. Both were buried in a mausoleum in San Diego, as was their son Otto, who died on 7. May 2014 [72].

David Skrabania, May 2017

![Document no. 35/1 Document no. 35/1 - Handwritten letter [in Polish] from M. Paledog from Cheltenham/England to A. Topolnicki.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-031-1a.jpg?itok=gfPskEix)

![Document no. 35/2 Document no. 35/2 - Handwritten letter from M. Paledog from Cheltenham/England to A. Topolnicki, [p. 2].](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-031-1b.jpg?itok=Df4ctKpD)

![Document no. 36/1 Document no. 36/1 - Envelope to the letter [Document 35] from Paledog to Topolnicki.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-031-2a.jpg?itok=krd42nL9)

![Document no. 36/2 Document no. 36/2 - Back of the envelope to the letter [Document 35] from Paledog to Topolnicki.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-031-2b.jpg?itok=K_dTfhNe)

![Document no. 38 Document no. 38 - Topolnicki is informed about the progress of his immigration application [ assurance is recognised].](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-033.jpg?itok=OKjuXvyn)

![Document no. 39 Document no. 39 - [Handwritten copy of the] birth certificate of Irma Saling, the wife of Aureli Topolnicki.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-034-1.jpg?itok=Qcvw5Oaz)

![Dokument Nr. 127/1 Dokument Nr. 127/1 - Personalausweis von A. Topolnicki mit Lichtbild und Informationen zur Person und Aussehen, zudem Information über die Deportation nach Lungenburg [Lundenburg] am 16.7.1943](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-096a.jpg?itok=pKJpAuzw)

![Dokument Nr. 127/2 Dokument Nr. 127/2 - Personalausweis von A. Topolnicki mit Lichtbild und Informationen zur Person und Aussehen, zudem Information über die Deportation nach Lungenburg [Lundenburg] am 16.7.1943.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/12890-097b.jpg?itok=RIjcT74Q)