EITHER YOU SEE IT, OR YOU DON’T. The topography of eternal return in the painting of Jerzy Skolimowski

“Ah! But verses amount to so little when one begins to write them young. One ought to wait and gather sense and sweetness a whole life long, and a long life if possible, and then, quite at the end, one might perhaps be able to write ten good lines. For verses are not, as people imagine, simply feelings (we have these soon enough) – they are experiences. In order to write a single verse, one must see many cities, and men and things; one must get to know animals and the flight of birds, and the gestures that the little flowers make when they open out in the morning. [...] There must be memories of many nights of love, each one unlike the others, of the screams of women in labour, and of women in childbed, light and blanched and sleeping, shutting themselves in. But one must also have been beside the dying, must have sat beside the dead in a room with open windows and with fitful noises.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Die Aufzeichnungen des Malte Laurids Brigge, Könemann, Cologne 1999, p. 21–22. (English language edition: The Notebook of Malte Laurids Brigge, The Hogarth Press, London 1959, p. 18–19).

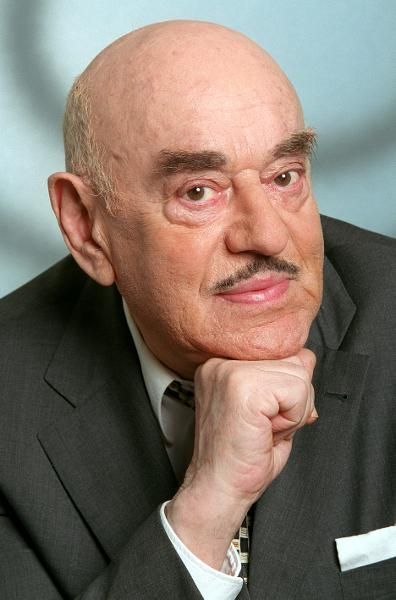

Jerzy Skolimowski shot ten good films, wrote ten good poems, and produced ten good paintings. Even after many years working as a curator, for me, the moment when the large canvases were brought out from the depths of the gallery depot, I could feel something very unusual happening. It became clear to me that until that point, I had never been so close to a work of a mature age, and that it was more than just a question of pure necessity; I also wanted to trust my first impression of a fulfilled artist. His childhood during the war (he was born in 1938) and the problems he faced as a young man during the post-war years, his early emigration and his battle for attention and recognition are just some of the episodes of his life that often left him confronted with a sense of alienation in relation to the “other”. At the same time, for an artist, being different can sometimes, though not always, be a comfortable state of being. In Skolimowski’s case, however, he accepts all the consequences that arose from being different. He knows that for art lovers, his paintings are like a riddle or even a secret. Yet by constantly searching for (and finding) empty spaces that are yet to be filled, he discreetly gives both critics and viewers of the paintings the opportunity to decipher the other areas within them. What is immediately evident is the unusual power of expression that reflects strength and the need to be set apart from the rest. This magic created by art is a necessary elixir for survival among artists and the public alike. However, it can also serve as a tool in the search for truth about life. And although art lasts for longer than life, and is at times more true than life, and although it may sometimes even be immortal, it is not life itself.

As a painter, Skolimowski most prefers situations that are borderline and which directly provoke a dichotomy, as a result of which the unfamiliar mixture of volatility and an idiosyncratic sense of grandeur generates a longing for security and stability. At the same time, the pain of existence is mixed with pure joy, perhaps even with excitement, which in turn is transformed into an intensely inspiring sense of insecurity (regarding one's own ability?), before returning in a highly melancholic fashion to the elementary questions: why am I here, and who am I really?

In life, as in art, the artist should allow themselves to be guided by knowledge of their self, which enables them to create the world that they can see in an endless play of the imagination that corresponds to this truth. They do this by taking responsibility for the freedom of their creative work. Even for the demanding, experienced observer, their paintings then become an ambiguous adventure in the sphere of art that is full of surprises. Which means are appropriate for discovering the independence that is carefully protected against the camouflage of arrogant self-satisfaction, and for finding the freedom that resides in solitude, so that it remains what it is in its perfect, incorruptible form? Pressing out the colours, mixing all colour tones, grasping them with one's fingers, putting away the brush and finally, mixing everything with whatever may come to hand.

Or perhaps simply painting? In its aesthetic, Skolimowski’s paintings are not characterised by exuberance. I would instead describe them as a compromise between the elegance of their statement and their intimacy. It is as though he has full power over the canvas, in defiance of all experimental conflicts, as though he were consciously creating his art. Consciously, and according to his own rules, he even submits to the game of chance. Even if he creates these rules within himself, this has no bearing on the fact that they owe more to ideals than to empiricism. Maintaining a sense of proportion is a luxurious privilege. One thing is certain: art is not life.

Skolimowski the filmmaker and Skolimowski the painter are worlds apart. In contrast to his work with film, where he is surrounded by an entire team of people, he welcomes the solitude of life as a painter, the indivisibility and complete independence of his decisions (as well as his responsibility for them). One has the impression that, as in film, he affixes scenes by making free use of different conventions in painting, while taking the best content and the best spaces in which we as viewers time and again experience his two opposite extremes: his sharp-minded analytical thinking and his reflectiveness, which permit us to make our own personal interpretations. Despite the different sources and tendencies from which he creates his language of expression, Skolimowski remains recognisable, yet at the same time distinct, and is not bound to any creativity beyond art. Could it be that for artists, their identity is an empty place into which others enter? Could it be that as a result of the post-modern relativism of our age, the problems of the artists and the viewers are becoming increasingly anonymised? For “viewers in a hurry” who simply want to cross off another exhibition on their list, painting like this presents quite a challenge. Starting from the actual realities, indeed, even from the tangibility of objects and events, Skolimowski transforms them into independent forms of being, and in so doing, creates a vibrant variant of modern painting. For him, abstraction is not really abstraction, since here, the access point – the metaphor – serves as a starting point. As such, the following applies: “Either you see it, or you don’t”.

With reference to Immanuel Kant, Jacques Derrida, in his aesthetic theory “The Truth in Painting”, warns against allowing a situation to develop in which the parerga, the trivialities, become more important than the essential that we are seeking. The parergon is simply an accessory in a space, something that exists beyond the work, even if it frequently triggers the creation of a work of art. Skolimowski, who frequently shifts between ergon and parergon, succeeds almost masterfully in balancing out the two areas. He is very aware that he is oscillating between fiction and truth, and that the path that he treads is not always a very promising one, even if he has chosen it himself. The only solution, therefore, is not to give in, to have mastery over the path, to subject it to one’s own requirements and ideally to engage with it, whereby here, rationality is not considered to be the highest cognitive authority, since its possibilities tend to be limited.

For Skolimowski, the credo of his artistic fulfilment clearly appears to consist of two imperatives: destroy and build. This occurs thusly: the ascetic, intellectual painting, in which we initially see no more than what we see, moves decisively towards the other side of the mirror; it asks questions and attempts to approach answers, although these are never unequivocal. In being aware of his own freedom, Skolimowski is also mindful of the freedom of the person facing him, whom he allows to make their own choice, while at the same time he finds a mode of entering into a dialogue with them. With discreetly inserted symbols, the artist equips the viewer with keys to a personal interpretation of his works, whereby he also perceives the meeting with the recipients of his art, which occurs in the reception, as an opportunity to deepen his self-knowledge and as an impetus for his continual process of change. Is that perhaps why the “viewers who are not in a hurry” are transfixed by the expression and calm portrayal, the impact of which lasts beyond the minutes spent in front of the pictures? Might they possibly notice the traumatic storms that gently cross over into light-filled narrations of one’s own satisfaction with a peaceful sense of permanence, only in order to experience the moment immediately afterwards when these beautiful conventions are broken by undisciplined transitions? In this way, we touch on the time references of Skolimowski’s painting, since time has an extremely important function in his artistic imagination and has an impact on the correct way of reading his intentions.

Time always exists concurrently, in many dimensions and on many levels. Thanks to the time that is actual, that is real, time that has already been experienced and time that is only imagined, everything can be construed multiple times and in different ways. Time is the creator of what is happening in the image; it slows down or accelerates the narrative in order to underscore it again and again with Skolimowski’s dichotomy of continuity and impermanence. At times, a space treated in this way loses its reality as an image, whereby both the creator and the observer know that they are moving between fiction and truth. And now I ask myself: might every profound interpretation be a kind of wishfulness for and questioning of everything? How should the end of the interpretation be determined in order to leave the sanctity of creation untarnished?

In my interpretation, Skolimowski’s paintings are wise stories about the nostalgia of the turn of the century, about how right it is to collect, preserve, and regain the past, and about life that often plays out on the edge of the abyss... They are also stories about truth in art, although perhaps the most important insight is that in the face of the constantly disappearing horizon, one remains on one’s own path, and although the horizon can be reached at the distance of an outstretched hand at most, that one continues, always remaining in motion, discovers new worlds and hopes for change. After all, so in art, so it is in life, even if art is not life.

Magda Potorska, March 2023