Opera as a place of memory. “The Passenger” by Mieczysław Weinberg. 2017 in Gelsenkirchen

It is a superhuman artistic challenge to transfer the cruelties of what was probably the largest consciously organised mass murder in the history of humanity, to the stage in the form of an opera. But the author, herself a survivor of Auschwitz, wanted to keep alive the memory of the atrocious deeds and simultaneously send us a reminder in a living place of memory. These considerations clearly weighed more heavily than the fear of the problems involved in translating the events into a literary and theatrical form.

The Polish Jewish composer, Mieczysław Weinberg (Polish: Wajnberg), fled to exile in Russia after the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, and lived in Moscow until his death in 1996. On the advice of Dmitri Shostakovich he chose to adapt the novel “The Passenger” (“Pasażerka”, Warsaw 1962), by the Polish writer Zofia Posmysz, for an opera of the same name. Shortly afterwards the Russian translation appeared in the periodical Inostrannaja Literatura. It portrays the memory of Auschwitz from the perspective of a culprit and this was probably the decisive reason for Weinberg to select the story. This utterly new view of events in a concentration camp made Zofia Posmysz famous. In 1963 the novel was filmed by Andrzej Munk in Poland and was subsequently used as a template for a number of opera and stage productions.

Although Zofia Posmysz agreed to a libretto being based on her book, she left this to Alexander Medwedew and Juri Lukin who did not keep strictly to storyline in the novel. Walter, a German diplomat, and his wife Lisa, have just set sail in a luxury liner for Brazil where Walter is due to take up a new post. They are both looking forward to a new and happy life and regard the cruise as a “second honeymoon” until their idyll is brutally interrupted by another passenger Marta. Lisa recognises Marta as one of the people she supervised in the concentration camp in Auschwitz, where she was only “doing her duty” as a warden. Nonetheless Lisa has always kept this episode in her life secret from her husband. The memories of the concentration camp are skilfully and excitingly woven into Lisa’s suspicions and fears that Marta might have recognised her once again. At the start, whilst she had been one of Marta’s supervisors she had treated her relatively humanely. But in the final analysis she remained more than true to the Nazi ideology by denouncing Marta’s fiancé Tadeusz, after they came across each other in the camp quite by accident. After witnessing their reunion Lisa sent Marta to the death block.

The dramatic tension in the opera grows as the size of the crime becomes increasingly clear. The score and the descriptions of the sufferings sung by the women prisoners one after another in German, Polish, Russian, French, Czech, Yiddish and English are shattering. The role of Tadeusz in Gelsenkirchen was sung by the Polish baritone, Piotr Prochera, and had a particularly striking and authentic effect on the audience.

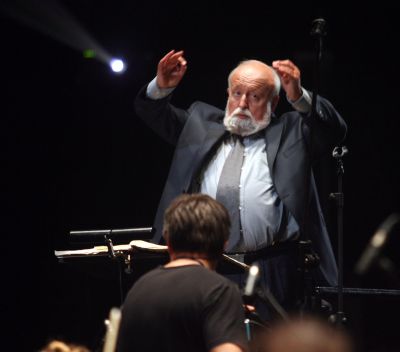

The tragic destiny of the prisoners is described in individual scenes, as in a movie or a documentary film. It is remarkable that, despite the huge volume of the instrumentation, the emotional music does not prevent us from understanding every word of the libretto. The libretto and translations into German are projected as surtitles above the stage. Although the music constantly stays faithful to the driving force of the production, thanks to the masterly skill of the conductor it remains subservient to the sung text and the crushing background.

One of the most unforgettable moments occurs when a Russian prisoner called Katja, sings a Russian folk song with no orchestral accompaniment. The incredible silence in the audience seemed to be the only acceptable reaction. Another similarly shattering scene was when Tadeusz, a violinist, refuses to play a waltz for the camp commandant and, instead, spontaneously plays the chaconne in D minor by Johann Sebastian Bach – an act of subordination that spells his death sentence.

The voices of the invisible choir, which emphasise and clarify the painful memories, seem like the prophecies of Cassandra. The tensions in the production reached their high point in the final scene when it becomes clear that these memories are the only way of truly dealing with the suffering, and that such memories are necessary as a warning for the future.

Zofia Posmysz was born in Kraków in 1923. In 1942 she was sent to the concentration camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau and three years later, in 1945, liberated in the concentration camp in Ravensbrück. She was present at the premiere of the opera “The Passenger” in Gelsenkirchen on 20th January 2017. At the end of the performance she was brought on stage to witness the lengthy standing ovations. This was the moment when her transparent efforts to understand the Germans and see them in a positive light seemed to turn into reality.

Jacek Barski, March 2017

Musiktheater im Revier Gelsenkirchen

The Passager

An opera in two acts by Mieczysław Weinberg

Libretto by Alexander Medwedew based on the novel of the same name by Zofia Posmysz (1962)

In German, Polish, Russian, French, Czech, Yiddish and English with German surtitles.

First concert performance

25th December 2006, in the “Stanislavski and Nemirowitsch-Dantschenko Music Theatre” in Moscow

First full production

21st July 2010, Bregenzer Festspiele

In repertoire in Gelsenkirchen

28th January to 23rd April 2017

The performances in Gelsenkirchen were accompanied by a comprehensive programme of side events, including two exhibitions on Zofia Posmysz, conceived by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków (Muzeum Sztuki Współczesnej in Krakau, MOCAK). One of the exhibitions on Zofia Posmysz was shown in the foyer of the Gelsenkirchen Musiktheater im Revier: the other took place in the Centre for Persecuted Art in the Solingen Museum of Art.

Trailer by Gelsenkirchen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VxBRolIg_7o

For further information on Zofia Posmysz (in Polish), see: http://culture.pl/pl/tworca/zofia-posmysz