Maria Kwaśniewska and the story of a photograph

Maria Kwaśniewska is born on 15 August 1913 in Łódź (Lodz), the daughter of Jan and Wiktoria Kozłowski. She has a peaceful childhood despite the fact, as she herself says, that her home life was very disciplined. Maria attends the girls’ grammar school which was named after Romana Sobolewska-Konopczyńska. It is here that she is discovered and mentored by her sports teacher Ludwik Szumlewski, who would later become a sports commentator for the local broadcasting service in Łódź and athletics trainer at Łódź Sports Club (Łódzki Klub Sportowy). Even at the first long jump training session, Maria Kwaśniewska astounds her trainer with her talent. When not quite 15 years old, the young sportswoman is awarded first prize for “promising sporting achievements” by the President of the Second Polish Republic, Ignacy Mościcki. Two years later, in 1930, she wins her first Polish championship in the long jump.

Her sporting career quickly gains momentum. The girl is a multi-talent, she really enjoys sport. She trains in everything that she can: Javelin, long jump, triathlon and pentathlon, volleyball and basketball and the team sport Hazena, the precursor to handball. However, her ultimate discipline is javelin, and for 15 years no one in Poland was able to beat her. In 1931, 1935, 1936, 1939 and 1946, Maria Kwaśniewska becomes a five-time national champion in this discipline. She wins a bronze medal in basketball at the third Women’s World Games in 1930 in Prague. An accolade that every athlete dreams of is an Olympic medal.

The Propaganda Games

The 1936 summer Olympics are hosted by Berlin. Three years earlier there was an outcry around the world when the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced the venue. The brutality of the National Socialist regime is well known. Teams from many countries, including France, Great Britain, USA, and the Netherlands, consider boycotting the games. In the end, the games are held in Berlin despite the protests. This decision is partly influenced by the fact that the winter Olympics in Garmisch-Partenkirchen in February 1936 were held without a hitch. Apart from which, the National Socialists promise the IOC that they will allow athletes of Jewish heritage to participate in the games. Helene Mayer, a fencer with Jewish roots, is among the athletes. However, this promise turns out to be nothing more than lip service because in 1933 a ban was imposed on all other Jewish athletes preventing them from training and from participating in competitions. This effectively means that they had no chance of qualifying for the Olympic Games.

Whilst the games are on, all signs denying Jews access to certain places are removed from the Berlin cityscape and the National Socialists refrain from other anti-Jewish activities during this time. But this is all just for appearances: At the same time, 30 km north of Berlin the Nazis have begun to build the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Sinti and Roma, who spoil the image of the Third Reich that the National Socialists want to show to the world, are rounded up in Marzahn on the outskirts of the city. The homeless and prostitutes all disappear from the streets of Berlin.

The little Pole

Poland sent 144 athletes, 127 men and 17 women to the Olympic Games in Berlin. Amongst them was the talented 23-year-old athlete Maria Kwaśniewska. On Sunday, 2 August 1936, the athletes go head to head in Berlin in adverse weather conditions. A strong wind is blowing and dark clouds gather over the Olympic Stadium. In the final of the Javelin, Maria Kwaśniewska steps up against two German athletes Othilie “Tilly” Fleischer and Luise Krüger in the battle for the medals. When it’s her turn she is completely focused, takes a couple of deep breaths, breathes on the tip of the javelin and throws.[1] Her javelin travels 41.80 metres. That wins Kwaśniewska third place and the bronze medal. Othilie Fleischer (45.18 m) wins, Luise Krüger (43.29 m) takes second place.

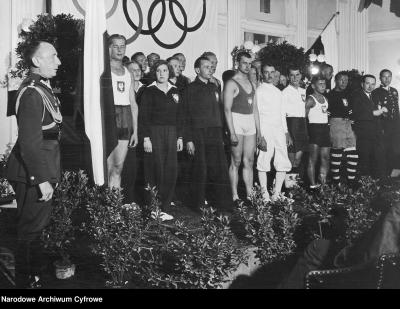

Adolf Hitler follows the contest between the athletes from his VIP box. After the medal ceremony, the Führerinvites the athletes to him so that he can congratulate them in person. The Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring, at that time the Minister for the Air Force of the Third Reich, are also in the box. It is on this occasion that Kwaśniewska famously insults Hitler. When Hitler says to her: “I congratulate the little Pole” she carelessly retorts: “I don't feel any smaller than you.”[2] To save the Führer from this embarrassing situation, the German press later reports that Hitler congratulated the “small Poland”, meaning the country and not the athlete. A memento of this event is a photograph of the three javelin throwers with Adolf Hitler, which will have a great impact only a few years later.

The war and the return home

When the Second World War breaks out, Maria Kwaśniewska is in Genoa, Italy, where, with a grant from the Polish Athletic Association (Polski Związek Lekkiej Atletyki), she is preparing for the 1940 Olympic Games in Helsinki, which are then cancelled due to the attack on Finland by the former USSR. At this time, Kwaśniewska is one of the best athletes in the world. When she hears about Germany’s invasion of Poland, she decides to leave Italy, which at that time was still safe, and to return to Warsaw. “I entered the country against the tide, as it were. People were already talking about war, so I could also have stayed [in Italy]. Everyone tried to talk me into staying, but I didn’t want to. At the Zebrzydowice border crossing, people looked at me as if I were mad. People were leaving the country in droves and I returned to Warsaw, even if I didn’t really know with what and how I was going to do it” – This is how Maria Kwaśniewska recalled this moment in an interview which she gave to the “Rzeczpospolita” newspaper in 2000.[3]

On 2 September 1939, introduces herself to Warsaw. The year before she had completed a course to become a paramedic. She also has a driving licence. She is immediately set to work as an ambulance driver in the area around the Warsaw power station in the Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie street and her job is to transport wounded soldiers from the trenches to the hospitals. She is awarded the cross for bravery (Krzyż Walecznych) by Stefan Starzyński, the former Mayor of the city, for her involvement in the defence of Warsaw. During the war, Maria Kwaśniewska meets her second husband, Julian Koźmiński. He is a director of the power station and commanding officer for the defence of Warsaw. But her luck doesn’t last. Koźmiński is arrested by the Gestapo and taken to the prison in Szucha allée. He was so ill when he left prison that he died shortly afterwards. Whilst he is still alive, however, the couple move to a house in Podkowa Leśna near Warsaw.

The free pass to living

In the period after their move, Kwaśniewska works non-stop for the resistance. At the beginning of August 1944, transit camp 121, also referred to as Dulag 121, is established by the Nazis. The camp is built for the civilian population of Warsaw driven from their house in the Warsaw uprising and after its suppression. Within six months, around 400,000 people are channelled through this camp. The Nazis make their selections there: those who are strong enough are assigned to forced labour, the weak, the old and the infirm are taken to concentration camps.

It is now that Maria Kwaśniewska remembers her photograph with Adolf Hitler hidden deep down in a suitcase. She takes it with her and shows it to the guards at the entrance gate to the Pruszków camp. The photograph works like a free pass. Of course, the gendarmes don’t know who Kwaśniewska is, but they don’t want to argue with the woman who knows the Führer personally, so they salute her and allow her to enter the camp grounds. Maria Kwaśniewska fetches prisoners out of the barracks, at first just a couple at a time, then later, encouraged by the reaction of the guards, whole groups. “I brought people out of the camp, going first to Pruszków and then to Podkowa Leśna, to my house. I had a transit camp in my house”, recalls Kwaśniewska adding: “The gendarmes raised their hands to their caps and let my transports through.”[4]

Just how many people owe their lives to the famous javelin thrower isn’t known. But the writer Ewa Szelburg-Zarembina and the writer and columnist Stanisław Dygat were definitely among them. Many of the people rescued by Maria Kwaśniewska kept in contact with her even many years after the war.

A life fulfilled by sport

At the end of the war, Maria briefly returns to sport. She is now 32 years old and her best years are behind her. Despite this, she becomes Polish javelin champion one more time, a final time, and represents her country a few times in basketball. In 1946, she bids farewell to active sport at the European Championships in Oslo, where she comes sixth in the javelin. She continues to remain faithful to sport . From 1947 to 1979, she sits on the board of the Polish Athletic Association and is also involved with the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF).[5] On top of this, she is a co-founder of the Olympians Club (Klub Olimpijczyka), long-term member of the Polish Olympic Committee (Polski Komitet Olimpijski) and holder of the “Kalós Kagathós” medal (2003).[6] Maria Kwaśniewska is also the first Polish athlete to receive the Olympic Order in bronze for her achievements around the Olympic Games (1978). In 2003, a memorial to Polish sport, which is named after her, is set up in the village of Spała (Park Pokoleń Mistrzów Sportu).

Maria Kwaśniewska, who remained active to the end, died in Warsaw on 17 October 2007 at the age of 94. Her final resting place is in the old part of the Powązki cemetery.

Monika Stefanek, September 2019