How a Polish Jew survived the Nazi regime in Frankfurt: Leopold Tyrmand’s autobiographical novel “Filip”

Entering the Parkhotel as a “counterfeit Frenchman”

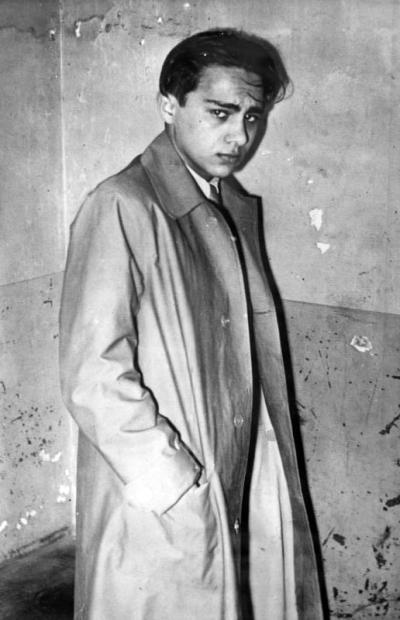

The Parkhotel in Frankfurt am Main in summer 1943. Despite the economy of scarcity caused by the war, the luxury hotel in Wiesenhüttenplatz is trying to maintain its noble façade – after all, the notable big name Nazis all come here to stay. Whilst the hotel’s permanent German workforce is fighting on the Eastern and Western fronts during the latter years of the war, it is a brigade of waiters made up of foreign labourers who proffer the hotel guests desserts made from starch and flavour substitutes, serve up coffee that is too thin, polish their worn out shoes to a high shine and brush down their worn tailcoats. One of the waiters is Filip Vincel, a 23-year-old former architecture student from Warsaw. He is a Polish-Jewish resistance fighter who only just escaped imprisonment for his conspiratorial engagement in the Soviet-occupied part of Poland and who would actually face annihilation in the German Reich because of his Jewish faith. But hardly anyone here knows his true identify and origins. With the audacious intention of surviving the Second World War “in the eye of the storm”, the young Pole got hold of forged papers, which showed him to be a French Catholic born in Warsaw, and reported voluntarily to the work effort in Nazi Germany.

Filip finds himself in the best company amongst the workforce at the Parkhotel. The few German waiters who are left, like Jupp and Leo, are either too young to be deployed at the front, or are trying to dodge the draft. Most of the workers, however, come from abroad: There is the Dutchman Piotr – he is Filip’s closest friend. And the Italian Savino, the Czech Vessely, the Frenchman Pierre, the Alsatian Marcel and the Belgian Abbelé. And then there is Filip, who, with his fluent French and German, fits the bill of the “counterfeit Frenchman” almost to a tee. Together they form a really harmonious group, united in their hate against the strict hotel manager and the German “master race”. And whilst the Allies wage their war against the Nazis on the fronts and in the air, the foreign waiters are waging war in the breakfast room at the Parkhotel. They snip too much off the valuable ration cards belonging to the German guests, steal bottles of fine Mosel wine from their employer as often as they can, and spit in the coffee drunk by the party bigwigs, officers and industrialists. Filip’s accounts of that time reveal the following: “I stood nearby, my heart filled slowly with the feeling of comfortable enjoyment, of sated longing, fulfilment, with a vindictive, disarming joy, like a warrior feels when he puts his foot on the truncated head of a vanquished foe”. Filip analyses his enemies with an almost ethnological interest and passes comment on those who are not smart enough to discover his true identity, using cutting words and overtones of situation comedy: “German nymph”, “offspring of the Nibelungen”. And although he does encounter Germans with differing attitudes towards National Socialism, his own experiences increase his vengeful hatred for the murderers of his people. Again and again the focus of the narrative turns to the complex relationships between the Germans and the “foreigners”, the narrative being flanked by the vivid descriptions of the menacing air attacks, the shortage of food, the omnipresent anti-Semitism and racism, and the insights into the everyday life of the Polish Jews disguised as Frenchmen in the middle of Frankfurt, a life which was not exactly without danger but which also had its comic moments.

Whether in Mosler’s swimming baths on the banks of the River Main, in the bars of the Main metropolis or at a picnic in Taunus, whenever the young men have some time off, the mood is relaxed. The considerable reserves of cash that Piotr shares so amicably with Filip open the doors to the best bars and restaurants in Frankfurt for the two friends. From time to time, they spend their time with Blanca, a non-conformist young German who Piotr has his eye on. To Piotr’s disappointment, however, she is more interested in Filip. His good looks and his status as a Frenchman persuade some ladies to have a fleeting dalliance with him or even to let him help them get over the absence of their husbands who are fighting at the front. Confident and unabashed, the Polish-Jewish outsider takes what life owes him. Sometimes, he lives like there isn't a war. Rebelliously nonchalant, he oscillates between resisting the horrific everyday conditions of war and adapting to them.