Dedicated to Poland: Jacek Kowalski (1950–2019)

An eventful life in the People’s Republic of Poland

Jacek Kowalski was born in Ostrów Wielkopolski on 5 May 1950 to a family with strong patriotic roots. His grandfather, Aleksander Dubiski (1886–1939), was a Polish Army officer and a doctor, and was a highly regarded member of the community in Ostrów Wielkopolski. When the First World War broke out, Aleksander was conscripted into the Prussian Army as a lieutenant and was assigned to a field hospital in Ostrów Wielkopolski. At the outbreak of the Greater Poland Uprising, he served as commander of the field hospital. He was one of the founders of the Republic of Ostrów (Republika Ostrowska, 10–26/11/1918). Later, he fought on the Lithuanian-Belarusian front during the Polish-Bolshevik War. During the course of the war, he was promoted to the rank of captain. After the war ended, he returned to Ostrów Wielkopolski, where he became the director of the district hospital. In November 1939, after Germany invaded Poland, he was arrested, together with 27 other members of the local elite. His family were deported to a camp. On 14 December 1939, he was executed in Winiarski forest near Kalisz. Aleksander Dubiski is buried alongside other participants in the Greater Poland Uprising in the cemetery in Ostrów Wielkopolski.

Jacek Kowalski’s mother, Maria Dubiska-Kowalska (1924–1998), continued the fight for independence during the Second World War. At that time, she was living in Warsaw, where she attended school and survived the siege of the city. In October 1939, she and her family returned to her hometown of Ostrów. After her father Aleksander was arrested, she and other family members were deported to the camp at Nowe Skalmierzyce. In January 1940, the German authorities decided to close the camp and deport the prisoners to Kielce in the General Governorate. She and her family were frequently forced to move from one place to another due to the difficult living conditions. First, she went to live with her family, before moving to Starachowice, where she remained for some time. To avoid having to work as a forced labourer, she first found a job at a local sawmill, before joining the “Reichswerke Hermann Göring” industrial conglomerate, where she was employed in the hard metal division. She soon found out that a group from the Association for Armed Struggle of the Home Army (Związek Walki Zbrojnej / Armia Krajowa) was active on the factory site. From 1942 onwards, Maria worked undercover as a liaison officer under the codename “Maryla” for a partisan unit led by Lt./Mjr. Jan Piwnik (1912–1944), codename “Ponury”. Her task was to bring reports to the “forest”. Despite the many risks involved, she succeeded in smuggling a large number of documents during this time, including the entire archive of the group’s commander, “Ponury”. For many years after the end of the Second World War, she remained silent about her underground activities. Her story and her dedication to the cause were made known to the public during the 1960s by Cezary Chlebowski, who wrote about her in the book “Pozdrówcie Góry Świętokrzyskie” (“Greet the Holy Cross Mountains”). After her children were born, she placed a great deal of importance on bringing them up as patriots and supporters of independence.

Jacek Kowalski went to primary school no. 4 and the III general lyceum in his home town. He passed his higher school leaving exams in 1968. He was interested in maritime trade, and moved to Sopot, where he sat the entrance exam for the “Higher College of Trade” (Wyższa Szkoła Ekonomiczna) (formerly the “Maritime Trade College”). Although he passed the exam, he was not accepted onto the course at first. As he recalled: “I passed the entrance exam, but I didn’t have enough points to get on the course, since I had no points for my family of origin, and I was not accepted”. He therefore decided to take an entrance exam for the university in Toruń. At the same time, it emerged that he would after all be allowed to enter the study programme at the faculty for international trade at the Higher College of Trade in Sopot, where he studied from 1968 to 1971. At this point, nobody could have known that events would suddenly take a tumultuous turn. In December 1970, he was staying with friends in Kołobrzeg. They returned to Sopot on 13 December. “I hadn’t heard anything about price increases. In Sopot, we found out that the workers were going out on the streets and striking”, he explained.

Simply out of curiosity, he and a friend travelled to Gdańsk to see what was going on there. In Gdańsk, he witnessed the evacuation of the voivodeship committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party (Polska Zjednoczna Partia Robotnicza) and the actions taken by the police and the civilian militias. The memory of what he saw stayed with him when he returned to Sopot. The following day, on 15 December, he travelled to Gdynia with Bogdan Gronowicz. Near Gdynia-Wzgórze Nowotki, they ran into a civilian militia patrol. After their identities had been checked, they were arrested and taken to an unknown location. After two days of solitary confinement, they were told that they were in the Wejherowo camp, where striking workers were being held. On 9 January 1971, the two men were released from the camp and Jacek Kowalski returned to Ostrów. In the interim, his family had been informed by the Citizens’ Militia that he had participated in the unrest on the coast. His arbitrary arrest and imprisonment were his first encounter with the repressive nature of the communist regime. After returning to university, he was told that he had failed all of his exams. He recalled this experience in his memoirs: “I didn’t pass a single exam in the winter semester. I could even guess why. My suspicions were confirmed during the German exam with Professor Rita Ras, who explained that she had to fail me, even though I was the best student in the year”.[1]

This decision prompted him to abandon his studies. He started work in a horticultural cooperative in Ostrów, but was sacked from his job due to the increasing repression. His precarious financial situation meant that he was forced to look for another job. Finally, he found employment in the state-owned layered laminate factory in Bernau near Berlin. However, soon afterwards, he was sacked from this job, too. It emerged during a factory inspection that he was being employed illegally, and he was expelled from the country. At the beginning of 1972, he again sought work in the GDR. This time, he was offered a job in the boiler house of the state-owned Elfe chocolate factory in Berlin-Weißensee. After a while, he was promoted to water replacement warder, and later to boiler warder. That same year, urged on by his parents, he began studying German language and literature at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. Thanks to the support of Dr Hubert Orłowski, he qualified for an academic exchange and in 1974, he enrolled at Martin Luther University in Halle (Saale), where he met the woman who would become his wife. As a student, he became the representative of the delegation of Polish exchange students and was monitored by the Stasi. Their interest in him stemmed from a speech he gave to mark the 30th anniversary of the People’s Republic of Poland and the 25th anniversary of the founding the German Democratic Republic, in which he called into question the liberation of the city of Halle by the USSR. Following this speech, he was taken away for questioning by Stasi officers.

“Every member of the delegation gave a speech. I was also required to make a contribution. After reading an inscription on the wall, ‘We thank the Soviet Army for the liberation of Halle’, I knew that I had to correct several historical facts and explain what really happened. I said that Halle – as I had learned from my textbooks at school – had been liberated by the American Army and that it had then been given to the Soviets in exchange for their Berlin sector. At this point, my microphone was switched off. The next day, Mr. Schmeiel from the Ministry for State Security, who was in charge of foreign students, came to pick me up. Two men whom I didn’t know were waiting downstairs in the student hostel, who accompanied the two of us to an apartment. (...) They tried to convince me that I had been drunk while I was giving my speech. (...) When I refused to back down, one of the men asked me whether I liked the grass in the GDR. I answered no, since here, there were chemical factories such as Buna or Leuna, and that everything was yellow and brown... After I had finished speaking, one of the men told me in German to get the f**k out. (...) After that, I decided to quit my studies”.

He then returned to his alma mater. During the course of his studies, he became interested in German literature. While preparing for his Master’s thesis, he met the Austrian writer Peter Turrini. Since he was unable to continue his research in Austria with his supervisor, he decided to accept another scholarship and to return to Halle. Moving to the GDR wasn’t just a good opportunity to see his fiancée again, but also to prepare for possible flight from Poland. Thanks to his Master’s thesis and the fact that at that time, Turrini’s works were not available in Poland, he was gradually able to put this plan into action. As Kowalski explained in an interview with the author:

“I studied in Poznań until July 1976. Travelling to the West was just a pretext, since I was due to write my Master’s thesis on Austrian popular theatre. This subject was chosen specially for me and my colleagues by Dr. Włodzimierz Bialik, since the word ‘popular theatre’ made it easier to leave the country. (...) I was first granted a visa for the Benelux countries, and then a transit visa for Germany. It was thanks to an invitation to visit France from a French citizen, now my wife, that I was given a residence visa for one month and a transit visa for Germany”.

On the path to independence

In July 1976, Kowalski travelled to Halle with a group of students, where he met with his fiancée. There, they both decided to travel to the West. However, prior to his arrival in France, he and other colleagues who had also decided to flee stayed illegally in Munich for several weeks. In Munich, he not only succeeded in finding work under a false identity, taking his name from a Dutch student whom he had met by chance, but was also able to live with this student in his apartment. The ruse only worked because the student had returned to the Netherlands for a period of time, and had left Kowalski his apartment and tax card, without which it would not have been possible to find work. However, the precarious nature of his situation and the constant uncertainty led him to travel on to France just a few weeks later. He remained in France until the autumn of 1976. During this period, he looked for ways of travelling to Germany legally.

“I stayed in France for about six weeks. After that, I wanted to return to Germany. Since I only had a transit visa for Germany and not a residence visa, the French authorities reported me to the Germans (...) since my visa for 24 hours had already run out. That was in Strasbourg. At that time, I thought that since Poles no longer required a visa for Sweden or Austria, I would wait until the consulate opened, get a passport photo of myself taken in the photo booth at the railway station, and then go to the consulate. (...) I lied to them, telling them that my brother was waiting for me in Vienna, which was why I needed a transit visa for Germany. They even issued the visa for free and without any trouble. I got on the train and travelled to Munich”.

Finally, at the end of 1976, after encountering problems crossing the border, he reached Kehl am Rhein in the Federal Republic of Germany. In November 1976, the police station in Ettstrasse in Munich issued him with a ticket to the Zirndorf camp. There, more events occurred that would have an important impact on his life. In the camp, he met interesting people, including Tadeusz Podgórski (1919–1986) and Włodzimierz Sznarbachowski (1913–2003) from Radio Free Europe.

“(...) In the camp, we, the Poles, were visited by two men. They were Tadeusz Podgórski and Włodzimierz Sznarbachowski, who later became my friends. They asked whether they should bring us books or other items. Some time later, they brought us the books. They visited us again twice”.

Jacek Kowalski was soon granted political asylum. He left the camp and moved to Augsburg, where he completed his studies in politics at the university and soon found a job. From 1977–1983, he worked as a German and history teacher at the refugee camp in Augsburg.

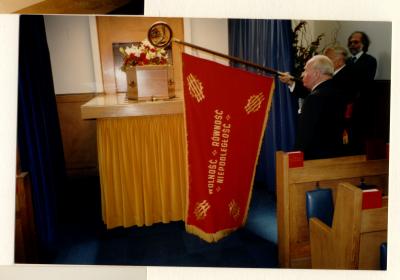

Right from the start, after settling in West Germany, he campaigned for Polish independence, becoming involved in political and social activities. This put him in the crosshairs of the security service of the People’s Republic of Poland. Information about his activities was documented by the department for espionage defence at the headquarters of the Citizens’ Militia (Komenda Wojewódzka Milicji Obywatelskiej, KWMO) in Kalisz. He was classified as a “person who represents a secret service threat”. In 1976, through his contact with Tadeusz Podgórski, he was accepted as a member of the Polish Socialist Party (Polska Partia Socjalistyczna, PPS). Soon afterwards, he organised the first PPS group in the Augsburg area. In September 1977, he was accepted into the Association of Polish Refugees (Zjednoczenie Polskich Uchodźców, ZPU), becoming the secretary of the 4th district of the organisation that same year. In 1978, he attended the 9th council of the Association of Polish Refugees as a delegate of the 4th district. At the same time, he was also involved in managing services for the group of PPS exiles in the Federal Republic of Germany. From 1978–1994, he worked for Radio Free Europe. One of the most important events for him at this time was the visit by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński to West Germany from 21–25 September 1978, whom he accompanied to meetings with representatives of the German episcopal conference in Frankfurt, Cologne, Munich and Mainz as his personal interpreter. On 23 September 1978, he stood next to Cardinal Wyszyński when he laid flowers at the monument to the murdered priests in Dachau concentration camp. This ceremony was also attended by the ambassador of the People’s Republic of Poland in Bonn, Andrzej Chyliński (the son of Bolesław Bierut).

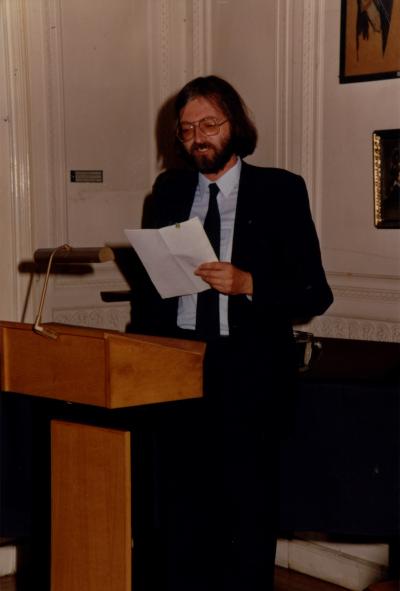

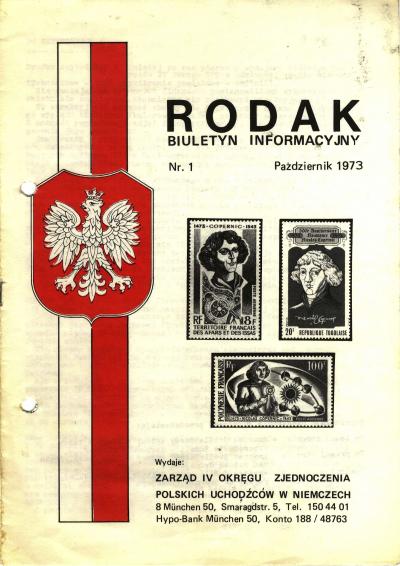

Aside from his social and political activities, Jacek Kowalski began working as a journalist, contributing articles to the “Dziennik Polski” and “Tygodnik Polski” magazines. In 1978, during a stay in London, he was elected as a member of the General Council of the Polish Socialist Party and met Lidia and Adam Ciołkosz. As a result of his social and political activities, he also forged closer ties with the PPS and Radio Free Europe. His friendship with Tadeusz Podgórski led to various joint initiatives, including the further development of the PPS structures in the Federal Republic of Germany. After a while, he became editor-in-chief of “Przemiany” magazine (1974–1987) and its German equivalent, “Die Wende” (1980–1983). Together with Eugeniusz Pietraszewski, he published “Rodak”, a magazine for the 4th district of the Association of Polish Refugees. It was published in Munich and covered the whole of Bavaria. In 1979, he was elected as a member of the German branch of the National Council of Poland. After the imposition of martial law, he smuggled banned literature into the People’s Republic of Poland and other eastern bloc countries. In 1981, the 9th division of the 1st department of the Ministry of the Interior of the People’s Republic of Poland (civilian intelligence service) became aware of his activities. In 1983, the district Bureau for Internal Affairs in Będzin became interested in him, as did the 2nd division of the voivodeship Bureau for Internal Affairs in Olsztyn in 1985 (counterintelligence). Officials from the voivodeship Bureau for Internal Affairs came to his apartment in Poznań and attempted to discredit him. At the same time, his closest family members who were living in Poland were tailed. It was not until 1990 that the security services lost interest in him. Kowalski discussed these activities in our interview:

“What kind of smuggling network was it? We were around a dozen individuals who regularly came to Germany. I even knew one of the men. His name was Makusz-Woronicz. (...) Before the war, he worked for the 2nd division of the general staff of the Polish Army. Later, he arrived in Germany and then London in a small Polish Fiat 126p. (...) He therefore had connections on the German-Czech border. He just had to wait for the right people to be there in order to pass through. (...) The Czechs didn’t make control checks; only the Poles did so. And then he sent reports. His codename was ‘Niedźwiedź’ (‘Bear’). It was [the same] codename that he used in the general staff. ‘Niedźwiedź’ sent messages... what was it that he said?... ‘The eagle has landed safely’. (...) and then you had to make a note in the report (...) how many books had been sent and who had received them: students, research staff”.

In January 1983, he joined “Zurich”, the Swiss insurance company, as a general representative. During the same year, he became chairman of the main committee of the Polish Socialist Party in the Federal Republic of Germany, secretary of the branch of the National Council and chairman of the PPS faction in the branch of the National Council. Throughout this period, he remained in contact with the leadership of the PPS in London. In 1986, he became deputy chairman of the branch of the National Council in West Germany. From 1987 onwards, together with the editor Bogdan Żurek, he began to bring together the Polish Socialist parties outside Poland. This culminated in the party congress in Bernried near Munich. From 1987 onwards, he was chairman of the Central Executive Committee and member of the General Council of the PPS in London. During the 1980s, he was chairman of the Polish Refugee Council for the Polish government-in-exile in London. In this role, he was involved in granting political asylum to Polish refugees in West Germany and Austria. He was also in contact with the Polish American Immigration and Relief Committee. In 1990, he attended the 25th congress of the Polish Socialist Party, at which he was again elected as a member of the Central Executive Committee and the party’s General Council. Following the breakdown in negotiations with the socialists of the PPS in Poland, he organised the Central Foreign Committee of the PPS, which remains active to this day. In 1993, he became chairman of this Committee. In this role, he participated in several congresses of the Socialist International, which had previously been headed by Willy Brandt. In 1992, together with foreign minister Krzysztof Skubiszewski, he attended the memorial service for Willy Brandt in the Reichstag. As Jan Kowalski recalled:

“(...) I was present at this state ceremony in the Reichstag, where we bid goodbye to Brandt before he was laid to rest in the cemetery in Berlin. At the ceremony, I represented the Polish Socialist Party, while Poland was represented by Minister Skubiszewski. After the ceremony, I had the opportunity to speak with the minister”.

In 1994, he became a member of the main committee of the PPS in Germany. In November 1997, at the final congress in Bernried, he brought his activities for the Polish Socialist Party abroad to an end. From 2001 onwards, he worked as a member of the editorial board of the “Bayerisches Bulletin”, which was published by the Association for the Promotion of German-Polish Understanding (Stowarzyszenie na Rzecz Porozumienia Niemiecko-Polskiego), and became deputy chairman of the organisation. He was also a member of the Polish Journalists’ Association (Stowarzyszenie Dziennikarzy Polskich), the International Federation of Journalists, the Polish Council in Germany and the Convention of Polish Organisations in Germany. In 2002, he attended the celebrations to mark the 50th anniversary of Radio Free Europe, which were held at the US Embassy in Warsaw. Together with Bogdan Żurek, he was involved in investigating the death of the priest Franciszek Blachnicki, the founder of the Christian Service for the Liberation of the People (Chrześcijańska Służba Wyzwolenia Narodów) in Carlsberg (Germany). In 2008, he supported the appeal to Poles made by Anna Walentynowicz. On 4 April 2011, he took part in the presentation of the book “Polska Partia Socjalistyczna. Dlaczego się nie udało? Szkice. Wspomnienia. Polemiki” in the Polish Cultural Centre in Munich, which was organised by the Institute for National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej) in Warsaw, the consulate general of the Republic of Poland in Munich and the Association for the Promotion of German-Polish Understanding in Munich. By now a pensioner, he spent many years promoting awareness of the activities of the Polish Socialist Party in West Germany and Radio Free Europe. He frequently attended meetings with Polish and German historians, at which he provided information about the complex events of the past and answered questions. On 18 June 2018, he was presented with the honorary badge of “anti-communist opposition activist or repressed person for political reasons” by the Warsaw Office for War Veterans and Victims of Oppression (Urząd do Spraw Kombatantów i Osób Represjonowanych). On 21 March 2019, he died suddenly in Augsburg. His funeral was held in France, and a requiem mass was held on 4 May 2019 in Ostrów Wielkopolski.

Łukasz Wolak, May 2019

Bibliography

From the archives:

- Archive collection of the deceased Jacek Kowalski (1950–2019)

- Archive collection of Łukasz Wolak

- Archive collection of the Research Institute on Polish Emigration in Germany after 1945 at the Historical Institute of the University of Wrocław (Pracownia Badań nad Polską Emigracją w Niemczech po 1945 r. w Instytucie Historycznym Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego).

Literature:

- Friszke, A.: Życie polityczne emigracji, Warsaw, 1999, p. 448.

- Gmyz, C.: Gdzie są teczki „systemu Polonia” – pytają emigranci, “Życie Warszawy”, 10–11/9/1994, [no page number provided].

- Kalczyńska, M. / Paszek, L.: Niemieckie Polonica prasowe (ostatnie dwudziestolecie XX wieku), Opole 2004, p. 221–222.

- Kowalski, J.: Polska Partia Socjalistyczna a Niepodległość, “Moje Miasto” no. 5 (September–October) 2018, p. 13.

- Pan Jacek się dąsa, “Trybuna Ludu”, 3/7/1985, [no page number provided].

- Polska Partia Socjalistyczna. Dlaczego się nie udało? Szkice. Wspomnienia. Polemiki, ed. Robert Spałek, Warsaw 2010.

- Teraz są sobą, “Trybuna Ludu”, 20–21/10/1984, [no page number provided].

- Włodarczyk, W.: Jacek Kowalski, “Kurier” (Chicago), 6/12/1988, no. 24, [no page number provided].

- Wojna nie była kobietą, “Moje Miasto” no. 5 (September–October) 2018, p. 6.

- Wolak, Ł.: Leksykon działaczy Zjednoczenia Polskich Uchodźców w Republice Federalnej Niemiec (1951–1993), Wrocław 2018, p. 121–124.

- Wolak, Ł.: Zjednoczenie Polskich Uchodźców w Niemczech wobec emigracji solidarnościowej w latach 1981–1989, in: Świat wobec Solidarności 1980–1989, ed. Paweł Jaworski and Łukasz Kamiński, Warsaw 2013, p. 703–717.

- W służbie dla Polski. Jacek Antoni Kowalski, “Moje Miasto” no. 5 (September–October) 2018, p. 12.

- Wygnańcze szlaki. Relacje uchodźców i emigrantów z Polski do Niemiec, collected and compiled by Adam Dyrko, Warsaw 2007, p. 85–96.