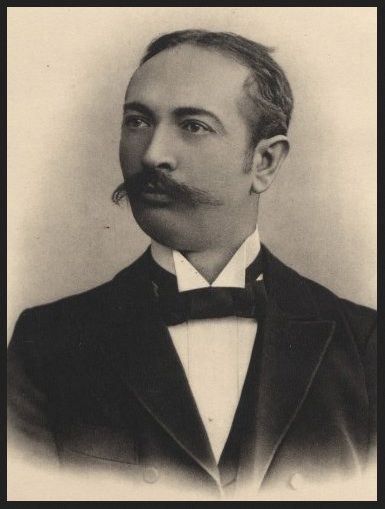

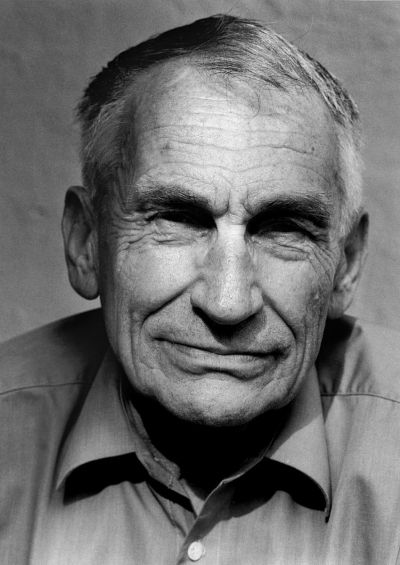

Collector, Physicist, Entrepreneur: Tomasz Niewodniczański

Tomasz Niewodniczański was born in Wilna (now known as Vilnius) on 25 September 1933 as the eldest of the Niewodniczański's three children. At this time, his father, Henryk Niewodniczański (1900–1968), was a professor of physics at the Stefan Batory University in Wilna. His mother Irena, née Prawocheńska, was a daughter or Roman Prawocheński (1877–1965), a professor of biology at the Jagiellonen University in Kraków. From 1937 to 1938, his father’s scientific work took Tomasz to Cambridge in England and to Poznań, where he spent part of his childhood. His grandfather, the engineer Wiktor Niewodniczański (1872–1929), was a director of the first electricity company in Wilna. Tomasz Niewodniczański’s first day at school in Wilna coincided with the day on which the Second World War began. After the school closed, he was given private tuition. The family left Wilna in March 1945 and after travelling for seven weeks in an overfilled railway car, they arrived in Lodz. His father took up an appointment as a professor in Wrocław in the same year. In 1946, the family relocated to Kraków, where Henryk Niewodniczański founded the Instytut Fizyki Jądrowej (Institute for Nuclear Physics) at the Jagiellonen University. For the first five years, the family lived in guest rooms in the Institute. Tomasz attended the Liceum Nowodworskie in Kraków and during this time discovered his passion for mountain climbing and skiing, and later for the theatre as well. In 1950 after his school-leaving exam, he started a physics degree at the Jagiellonen University which he finished in 1955 with a master’s thesis in experimental physics. His younger brother, Jerzy Niewodniczański (born in 1936), opted for the same discipline and later became an acknowledged professor of nuclear physics at the Jagiellonen University. From 1955 to 1957, Tomasz Niewodniczański worked at the Instytut Badań Jądrowych PAN (Institute for Nuclear Physics at the Polish Academy of Sciences) in Świerk near Warsaw. He then carried out research at the Institute for Physics at the Technical University in Zurich (ETH). It is here that he wrote his thesis on nuclear physics about neutron scattering and remained at the university as a research assistant until 1963. In Zurich, he met his future wife, the German architecture student and subsequent professor, Marie-Luise Simon. Their wedding was held in Trier. The young couple then moved to Poland. In 1965, Tomasz Niewodniczański took over the management of the Samodzielne Laboratorium Budowy Akceleratora Liniowego (Independent Laboratory for the Construction of a Linear Accelerator) at the Institute for Nuclear Research in Świerk, whilst his wife Marie-Luise had children and worked as an editor and translator from German into Polish. In the sixties they had three sons: Matthäus (born in 1963), Jan (born in 1965) and Roman (born in 1968).

In 1970, the first particle accelerator went into operation at the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Switzerland. The German-Polish Niewodniczańskis returned to the Federal Republic of Germany. Tomasz Niewodniczański then worked at the heavy ion institutes in Heidelberg and in Darmstadt. In 1973, after 18 years of academic work and the publication of numerous scientific articles, he entered the world of business thanks to an offer from his father-in-law to join the family firm Bitburger Brauerei Th. Simon, the beginnings of which date back to 1817. Tomasz Niewodniczański started out as the Director of Personnel responsible for around 2,000 employees. He was valued and well liked by everyone, so much so that he was soon known simply as “Doctor Niwo”. Shortly afterwards, he took over the finance department and became co-owner. When Tomasz Niewodniczański retired at the end of 1998, he noted with pride an annual beer output which had shown a seven-fold increase during his tenure, and an 8% market share for the brewery in Germany.

The income from his professional activities allowed Niewodniczański to build up a cartographic collection which, today, is considered one of the largest and most valuable private collections in Europe. Tomasz Niewodniczański used all his money and all his available time to buy the exhibits, although the actual monetary value of the collection is difficult to estimate. Experts price it at many millions of euros, with a value of 100 million euros even being mentioned. Tomasz Niewodniczański discovered his passion for cartography in 1967, when his wife gave him a view of Damascus from the print works of Braun and Hogenberg dating back to 1576.[1] Niewodniczański had a been a keen collector since discovering a liking for postage stamps as a child. Dozens of the objects that he collected over the course of forty years are maps and atlases with illustrations of Polish regions since 1815. With the exception of the work of Gerard de Jode with the portrait of Stefan Batorys, the collection has all known cartographic representations of Poland.[2] This goal of completeness inspired the collector’s work from the very beginning. The objects were acquired in renowned auction houses and from private individuals, especially in Western Europe. However, the portfolio of Polish memorabilia and maps, in particular, contained works that could no longer be found in Poland. These rare iconographic pieces include the Warsaw Vedutes by Bernardo Belotto Canaletto, P. R. de Tirregaille's Warsaw city map from 1762, a cityscape of Kraków from the pen of Matthäus Merian and the map of the city of Danzig from 1812 created under Napoleon.[3] But Niewodniczański also owned 1,000 sheets of German maps and 200 maps of the Duchy of Luxembourg to which Bitburg, the city in which he lived, belonged. His primary focus, however, was on Polish memorabilia or Polonica. He wrote in the foreword to the catalogue published for the exhibition entitled “Imago Poloniae. The Polish-Lithuanian Empire in maps, documents and old prints in Tomasz Niewodniczański’s collection”: “Only many years later, after emigrating from Poland at the beginning of the seventies, did I develop a more serious “professional” relationship with my collecting, which was certainly linked to leaving my homeland and my longing for it and to my early interest in history.”

When Niewodniczański acquired objects, they could be entire portfolios, as in the case of the collection of old maps of Poland by Halina Malinowska in Geneva or in the case of the lot of 360 parchment manuscripts from Łańcut, which Alfred Count Potocki realised towards the end of the Second World War.[4] With this in mind, he acquired around 400 documents and letters from the Radziwiłł family in London. After the death of Aleksander Janta-Połczyński in 1976, in New York he bought Mickiewicz’s letters to Odyniec, as well as old maps.[5] This was the trigger for Niewodniczański to start collecting famous old autographs and in this field as well the testimonies of all Polish kings since Casimir the Great.[6] In New York in 1996, he bought around 140 manuscripts and typescripts by Julian Tuwim from the 1920s and 30s which were then published in 2000.[7] This part of the collection was also home to around 200 letters from Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz to Artur Błeszyński.[8] In Portugal, Niewodniczański acquired more than 200 letters from Kazimierz Wierzyński.[9] The real gems of the manuscripts include the letter from Empress Katharina II to Stanisław Poniatowski, in which she promises the Truchsess of Lithuania the Polish throne, interesting documents penned by Tadeusz Kościuszko, numerous letters from Napoleon Bonaparte and the letter from Captain Charles de Gaulle describing his participation in the Battle of Warsaw on 15 August 1920. The collection also contains books with dedications from authors and famous personalities and more than 1,500 letters from prisoners in German concentration camps.

A valuable exhibit from Tomasz Niewodniczański’s collection is the “Moszyńskiego Album”, a notebook containing 99 pages on which Adam Mickiewicz wrote 42 poems during his stay in Crimea and in Odessa. When the Niewodniczańskis visited Poland in 1993, the album was stolen, although the actual object of the thieves’ desire had been their car and not the extremely valuable notebook in its boot. Negotiations with the thieves went on for three years before the album was able to be bought back.

In the garden of his Bitburg house, Tomasz Niewodniczański had rooms built in an underground bunker to house his exhibits, creating ideal conditions for storing his collection. Along with this archive, he set up an atelier for restoring old papers and employed a curator: first Dr Peter H. Meurer, then Dr Kazimierz Kozica, who supported him in the last ten years of his life. The work of the two curators helped him to establish the collection within the scientific world. Niewodniczański published catalogues and original editions. Two volumes of the series “Cartographica Rarrissiia” (Alphen aan den Rijn) were devoted to his cartographic collection in 1992 and 1995. He visited exhibitions and conventions, supported scientific research, financially as well, in connection with objects in his collection and emerged as an author in his own right of numerous publications on the history of cartography. However, Niewodniczański was never able to complete the most prominent book project about his collection. The project involved extensive research that he had carried out in around 300 libraries and collections throughout the world over the course of 20 years working with renowned scientists. His aim was to publish a complete catalogue of cartographic representations of Poland which, alongside facsimiles and the descriptions of the maps, was to contain historical, geographical and bibliophile classification. The creators of the catalogue also wanted to provide information about maps that had supposedly not been passed down.

By acquiring manuscripts of Polish literature for his collection, Niewodniczański also brought them back into cultural circulation. The “Mickiewiczana” was published in a two-volume edition with the scientific assistance of Janusz Odrowąż-Pieniążek and Maria Danilewicz-Zielińska: “Mickiewicziana w zbiorach w Bitburgu”, (vol. I, Warsaw 1989, vol. II, Warsaw 1993). At the end of 1999, he took the initiative to publish the book “Julian Tuwim – Utwory nieznane” (Julian Tuwim. Unknown Works), which was based on the manuscripts he had acquired. Tomasz Niewodniczański was happy to have his collections on display and exhibited them on a total of 27 occasions in Holland, Spain, Germany, Poland and Lithuania. The largest exhibition with 2,272 exhibits was called “Imago Poloniae” and was held in Berlin for the first time from 2002 to 2003 and subsequently in Warsaw, Kraków and Wrocław.

In the midst of all this, Niewodniczański proved to be a generous patron transferring objects from his collection to the organisers of the exhibitions. In 1998, he gave the Uniwersytet Szczeciński (Szczecin University) 100 historical maps of Pomerania from the 16th and 19th century and around 200 views of Szczecin and towns from the region. In 2002, he gave 200 old maps and views of Silesia to the Ossolineum in Wrocław (Ossolinski National Library in Wrocław).

In the final years of his life, whilst pondering the future of his treasures, Dr Niewodniczański announced that he would be donating his collection of Polish memorabilia to museums in Poland, under the condition, however, that the Republic of Poland returned the so-called”Berlinka” collection to the State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage. This collection, along with manuscripts from Goethe and Mozart, had found their way to Poland in all the confusion of the Second World War.[10] He broadened this proposal by asking the Germans to set up a foundation with a capital of 300 to 400 million euros to acquire any Polish memorabilia offered at auctions around the world for Polish museums. Whilst this idea was debated by the Polish and German media, it did not actually come into fruition.

Because of this, Tomasz Niewodniczański changed his instructions once more before his death. He realised his dream and handed over the lion’s share of his Polish memorabilia to the Royal Palace in Warsaw on permanent loan . The collection included around 2,500 maps, 40 Polish atlases, around 150 cityscapes, royal facsimiles, 900 old prints, around 4,700 historical and literary autographs and signed books of renowned authors. The rest of the collection remained in the Niewodniczański family.

In 1991, Tomasz Niewodniczański received an honorary doctorate from the University of Trier for his achievements in making important Polish cultural works available to the public. In 1999, the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Applied Sciences appointed him Honorary Senator. In 1993, Niewodniczański was honoured with the Federal Cross of the Order of Merit on ribbon and in 1998 with the Commander's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland. In 2002, he received the Cross of the Order of Merit (First Class) of the Federal Republic of Germany. In 2004, he was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Lithuania. In 2009, the Republic of Poland decorated him with the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, and his wife Marie-Luise was given the Gloria Artis gold medal for services to culture.

Tomasz Niewodniczański died on 3 January 2010 and was buried in the cemetery in Bitburg. In line with his wishes, his headstone bears the inscription: “Collector, Physicist, Entrepreneur”.

Joanna de Vincenz, May 2018

(All footnotes are comments made by the german translator Brigitte Nenzel).

Literature:

Thomas Niewodniczański (publ.), “Ich bin gesund und fühle mich wohl”. Briefe polnischer Häftlinge aus den deutschen Konzentrationslagern, translated by Marie-Luise Niewodniczańska, exhibition catalogue from the collection of Thomas Niewodniczański of the Historical Society of Prümer Land e.V. in the customer service hall of Bitburg-Prüm Kreissparkasse in Prüm, Prüm 2009.

Brückenschlag. Polnische Geschichte in Karten und Dokumenten, exhibition catalogue in the State Library of Prussian Cultural Heritage in Berlin from 18 April to 8 June 2002.

Danzig. Alte Stadtansichten, Landkarten, Dokumente. Auswahl aus der Sammlung Tomasz Niewodniczański. Exhibition at the German Poland Institute in Darmstadt, Haus Deiters, 13 October – 17 November 2000. Published by the German-Poland Institute in Darmstadt. Exhibition and catalogue Kriemhild Kern and Matthias Kneip.

Imago Germaniae: Das Deutschlandbild der Kartenmacher in fünf Jahrhunderten, from the map section of the State Library of Prussion Cultural Heritage in Berlin and the Niewodniczański, Collection in Bitburg, exhibition catalogue in the State Library of Berlin from 23 September to 9 November 1996. Exhibition and catalogue: Lothar Zögner. With an introduction by Joachim Neumann.

Thomas Niewodniczański (publ.), Mickiewicziana w zbiorach Tomasza Niewodniczańskiego w Bitburgu, in conjunction with the German-Polish Institute in Darmstadt, Vol. I, Warszawa 1989, Vol. II, Warszawa, 1993.

Dieter Bingen, Peter Oliver Loew (publ.), Polen. Kurze Geschichte einer langen Geschichte. Mit Illustrationen aus der Sammlung Tomasz Niewodniczański, accompanying booklet to the exhibition “Imago Poloniae” in the Hessen State Museum in Darmstadt from 30 April to 18 July 2004, German Poland Institute, Darmstadt 2004.

Doktor Niwo. Włodzimierz Kalicki in conversation with Tomasz Niewodniczański, [in:] Gazeta Wyborcza dated 23 July 2007.

Andrzej Michał Kobos, Polska Akademia Umiejętności, vol. XI, 2012, p. 149–192.

Joanna Skibińska, Porträt: Zu Besuch beim Sammler Tomasz Niewodniczański / Z wizytą u kolekcjonera Tomasza Niewodniczańskiego. Portret, [in:] Dialog. German-Polish magazine No. 72–73 (2005/2006), p. 107–115.