The Black Madonna of Częstochowa in Essen-Altendorf

The ‘black’ Ruhr region

The vibrancy of the Polish-speaking community today is in part due to the arrival of so many Polish Catholics to the booming industrial region around the Ruhr river at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. After all, the history of Polish-language pastoral care along the Ruhr goes back beyond the creation of the diocese of Essen in 1958. During the 19th century, Poles were already arriving in the Ruhr region in large numbers, seeking work in the newly established industrial centre. In order to be able to continue their Catholic way of life far from their homeland, they founded a number of different groups and associations. For the city of Essen alone, there are records of 16 (!) organisations that were active before the Second World War. The Eucharist was celebrated in Polish in nine congregations in Essen right through to the early 1930s. The myth of the ‘red’ Ruhr region is therefore not entirely accurate – neither then, nor now. The Catholicism of the earliest Polish miners meant that for a long time, the population in the Ruhr region tended not to vote ‘red’, but rather ‘black’; in other words, they voted for the Catholic Centre Party.

Before and after 1945

The rise of National Socialism caused upheaval among the Polish Catholic community along the Ruhr. The cult of Germanness promoted by Hitler and his vassals brought about a temporary end to foreign-language masses and to Catholic life as a whole. The Polish Christi society for the pastoral care of emigrants mentioned earlier organised the re-establishment of the Catholic community after 1945. During the Second World War, the order had already smuggled four priests from Poland over the German border incognito to provide spiritual care for Polish forced labourers. In the post-war years, they continued to support the community in North Rhine-Westphalia, this time on an official basis. After the alleged “zero hour” in 1945, a great deal of hard work and commitment was invested in providing pastoral care for Polish emigrants, with a support organisation for men, a school and a centre offering charitable services. There was close cooperation between the Polish missionaries and Bishop Franz Hengsbach (1910–1991), who since his vicariate in Herne had been a particularly important figure in providing spiritual support for Polish Catholics, and who later played an important role in the process of reconciliation between the German and Polish episcopal conference. The Polish-speaking congregation also worked closely with ‘worldly’ Polish organisations in the region; here, groups that supported the government and those which were critical of it were unified by their Catholic faith.

The “Committee for the Defence of the Parish”

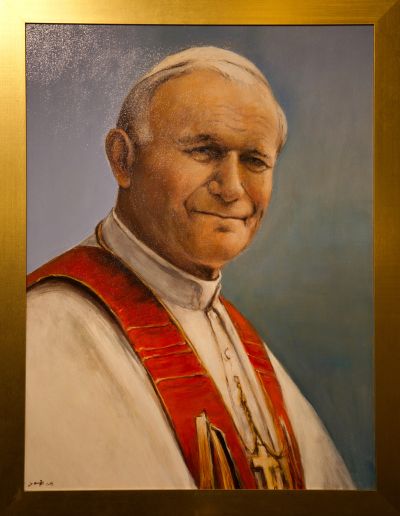

However, the history of the Polish-speaking Catholic community in Essen is not purely a success story. Since the 1980s, Polish organisations in Germany overall have faced the challenge of a dwindling membership. In 2005, in light of these declining numbers and the general restructuring of the diocese, the bishopric of Essen felt it necessary to axe the funds for one of the vicar posts, which led to a drastic response within the community. The removal of the vicar would have meant a reduction in the number of Polish services and other activities within the congregation. The decision was made to create a “Committee for the Defence of the Parish”. In the view of the committee members, the decision of the bishopric of Essen was unacceptable, since at the same time, John Paul II had declared 2005 the year of the Eucharist. Was it not a contradiction in terms, in the face of such an initiative, to do away with a priest’s post, and thus also the post of a celebrant? Not only that: the number of people attending mass had just begun to increase again. Many members of the community feared that losing a priest might lead to further measures, including even the abolition of the Polish mission. Finally, an agreement was reached that the vicar’s post would remain intact due to the high level of commitment among the congregation, which culminated in a signature campaign. Just a few weeks later, it was announced that the Polish Catholic mission would no longer be based in the St. Mary’s church in Essen-Steele. When Bishop Genn’s ideas for this restructuring process were first read out in a mass before the pulpit, some of the worshippers who were in attendance stayed on after mass had ended to pray for a fortuitous future for the mission – and knelt before the Madonna of Częstochowa. It would thus not be accurate to simply claim that Catholicism in the Ruhr region in the 21st century is in decline, as the example of the black ‘Maria’ in Altendorf shows.

Florian Bock, October 2021

Further reading:

Leonard Paszek (ed.): Dzieje polskojęzycznego duszpasterstwa w Essen. Geschichte der polnischsprachigen Seelsorge in Essen, Essen/Katowice 2007.

Borrowed with the kind permission of the Aschendorff Verlag publishing house

Original article:

Florian Bock: Das katholische Milieu lebt? Die Schwarze Madonna von Tschenstochau in Essen-Altendorf, in: Florian Bock, Sebastian Eck, Miriam Niekämper and Lea Torwesten (eds.): Geschichte(n) des Bistums Essen in 30 Objekten, Münster 2021, p. 138–143.