The author and film-maker Konrad Bogusław Bach. Between Poland and Germany

Konrad Bogusław Bach was born in Nakło nad Notecią in 1984. Soon afterwards, his parents moved to a rural area near the town, and his early childhood memories revolve around the chicken shack and his attempts to fry eggs on a sunny rock with one of the boys next door. He also clearly remembers his grandfather sitting in front of the piano with his fishing rod and tackle, hoping to catch the mouse that lived inside, as well as the big open sky above northern Poland. He also recalls playing chess with his grandfather, although naturally, his memories have been coloured over the years by family anecdotes and his own accounts of his childhood. At any rate, it was his grandfather who taught him to play chess. At first, he would let the boy win, so that he learned to enjoy the game; later, he would play “properly” so that the young Konrad would learn not only how to play, but also how to lose. Young Konrad never liked losing, however. If his beloved queen was taken, he would cry and throw a tantrum. Soon, his grandfather began to fear the games of chess, although he remained steadfastly true to his educational principles: the young boy would have to learn to get to grips with real life. Sometimes, other people are simply better than you.

Even so, life was good. It could have continued that way, but Konrad’s parents wanted more. They were keen to emigrate to the West, with all the promise it held. And didn’t they have relatives living in the USA? During the late 1980s, it wasn’t easy to get there from Poland. First, they needed an address in West Germany. They had one to hand: from a German couple whom they had helped in Poland when their car had broken down. At the border control hall at Friedrichstrasse station known as the “Palace of Tears” (Tränenpalast), they had to formally present themselves to the East German authorities in order to obtain a visitor’s visa. According to a family anecdote, the GDR officer was highly sceptical when he looked at the young family and their application papers. Were these lively, energetic young people really to be trusted? Might they never come back once they had crossed the border? Apparently, the young Konrad then suddenly grabbed his behind and said: “I really need to poo!”. The official recognised the urgency of the situation and let the Bach family pass. In Hamburg, they had planned to meet with another family from Poland and then take a plane to the United States. However, the Bachs arrived too late; instead, they spent some time in Hamburg in 1989, and quickly realised that the money from the sale of their small house and car would only suffice for a few weeks in the golden West. There was no question of buying an expensive air ticket. Instead, they headed for Friedland, near Göttingen, where there was a large reception camp for ethnic German resettlers. Konrad Bach still has vivid memories of the large TV in the recreation room, where he saw David Hasselhoff as Knight Rider for the first time. He loved watching the man with curly hair tearing through the desert in his black car... Fantastic! The “home kindergarten” (domowe przedszkole) simply couldn’t compete. The Bachs, who until that point had been known by their Polish name, Blechacz, were quickly officially recognised as native German resettlers. They legally became German and were even given a new name. They also received permission to work. Konrad’s parents lost no time finding jobs. In her new home in southern Hanover, his mother trained as an industrial management assistant and was later taken on as an employee of the city’s cemetery administration. His father first found work as a landscape gardener, then as a caretaker in green space maintenance. When they weren’t working, his parents learned German and spent time with Konrad and his brother, who was two years younger. Later, the two would be joined by a sister and twin brothers. Konrad Bach remembers that despite being so busy training and learning German, his mother still found time to help him and his brother with their homework, answer questions and help them find their way in their now homeland. “Now I realise how important that was”, he says, now aged 40, after spending a period of time working as a primary school teacher. He quickly learned German. For him, German is now his mother tongue, even if he is aware that this might sound strange. As a primary school pupil, he not only learned German at school and on the street, but also from TV. When he and his brother went to church with his parents on a Sunday and didn’t recognise the songs that were being sung, they would simply join in with tunes they had learned from TV adverts. The Bach children were quite happy to sing along with the melodies for “Ültje” nuts, Allianz insurance deals or Parma ham.

At the primary school in the Döhren-Wülfel district of Hanover, the atmosphere was less reflective than at the Sunday services. Konrad Bach remembers that there were a lot of fights. “You didn’t get bullied; you got hit”, he says, adding: “There were a lot of kids from Poland at the school, but the Silesian community separated themselves within the Polish community. My brother and I had more trouble from them than from the Kazakh Germans or the children from former Yugoslavia.” Fights and foul language were the norm at his school, he says. Today, he reflects that the constant fighting might have been partly a symptom of the fact that the resettlers tended to be regarded by the majority society as a “lower caste”, and that the boys in particular wanted to vent their frustration as well as proving their worth in competition with each other. Of himself, Bach says: “I was already a competitive type at an early age, and I simply thought this was part of my nature. Perhaps it also had something to do with my position as an immigrant, though.” One thing is certain, however: Konrad Bach often felt isolated in his youth. The Germans weren’t interested in his Polish roots. Often, they couldn’t name more than two cities in Poland, and knew nothing about Polish culture and the Polish way of life. He was also not seen as being German, however – while in Poland, he was increasingly no longer regarded as being a “real Pole”. He felt alien and nowhere really at home. Instead, he found his own place to call home in literature. It all started when a friend in the fifth grade lent him the Jack London classic “White Fang”. He loved the adventure story from the far north. He went on to read other adventure novels, such as “The Last of the Mohicans” and “The Three Musketeers”. They were followed by Thomas Mann’s novels, which he loved for their language and for the recognition that it is possible to reflect on your own behaviour. When it came to Dostoevsky, he was struck by the opposite insight: that people ultimately remain a mystery even to themselves. A cousin gave him a reading list with “good literature”, which he worked through with zeal. Aside from the hugely successful Polish science fiction author Stanisław Lem, Homer and Kurt Vonnegut, he also discovered favourites of his own, such as Wolf von Niebelschütz.

For Bach, literature was a way of coping with the attempts by his fellow pupils to assert themselves through fights in the school playground. He cultivated a pacifist stance and refused to sign up for military service. As a Zivi, or “civilian volunteer”, he moved from Hanover to Freiburg, where he worked in a hospital. On the one hand, he planned to study theology and philosophy in the city later on, while on the other, an extra bonus was paid for every kilometre of distance from the volunteer’s hometown.

“It was a great time”, he remembers. “I was doing something useful; from my perspective, I had a lot of money, and I got to know a very different part of Germany.” However, Bach later moved to Berlin to study at the Free University after opting for drama and theology instead of philosophy. It was a logical choice, since he had been writing for several years, and had produced a play he had written himself, “Gilgamesh and Ishtar” for his Abitur school leaving exam. At university, he came into contact with very different types of people, from the rather stuffy, serious theologians to the extroverted, partygoing drama students. Bach vacillated, preferring sometimes one subject and the kind of people who studied it, then the other. In the end, however, questions around the existence of God and the meaning of life faded into the background, while the joy of theatre took on greater importance. The attitudes that prevailed in the Berlin theatres presented a serious challenge to Bach, who had conservative views about how plays should be staged. In time, however, he grew more open to the new forms and became a big fan of post-dramatic theatre. The subject of his Master’s thesis, which he later further developed in his dissertation, was “Laughing during a performance” (Das Lachen in der Aufführung). He explains, “In theatre studies, the focus is often on how the audience responds to performances. The discussion revolves around them being moved, energised or baffled. In my view, though, too little attention had been paid to laughter.”

Konrad Bach enjoys laughing himself, and likes to make other people laugh, too. For him, literature, theatre and opera are always also a form of entertainment. He describes his work on his dissertation, which was funded by a stipend from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) as a “golden time”. He attended a colloquium every two weeks, but other than that, he was free to spend his time on research and reading, academic work, several periods of work experience at the theatre, and the production of short films. These films were usually about romantic relationships – presented in a humorous way. However, the subject of Bach’s short film “Magdalenas Akte” (“Magdalena’s File”) is a woman who finds her personal file in an archive and is able to change it. The five-minute version of this film was shown at numerous festivals and it won several prizes.

Bach’s areas of interest go even further beyond theology and theatre, dissertation and short films, however. Having made Berlin his home, he went on to study classical philology “on the side” – a subject that he had discovered as a theology student, and which fascinated him. This is of particular interest due to the fact that while working on his dissertation, Bach also trained as a teacher and took the state “Master of Education” exam. Despite his romantic streak, he never completely lost sight of the need to think in practical terms. There were very few secure jobs available for theologians and theatre specialists, and Bach would probably have had better chances of getting work as a theatre director if he had studied the subject and spent time shadowing directors in Berlin in his early 20s. He spent his probationary period as a teacher at the Heinrich Schliemann grammar school in the Berlin district of Prenzlauer Berg, where he enjoyed teaching Latin and ancient Greek. He then spent over two years at a primary school in nearby Wedding, where he lived with his wife and daughter, born in 2014. Naturally, he did not teach ancient languages there, but rather maths, art and sports. However, in his extracurricular “Greek myths” group, he awakened an interest among some of the pupils in the ancient myths which he himself had come to love a boy. He also ran a chess club, passing on what he had learned from his grandfather. Konrad Bach also has fond memories of the Erika Mann primary school: “A great head teacher, good ideas and just around the corner from where I lived!”

Today, he teaches at a grammar school in Frankfurt/Oder. However, he, his wife and their now four children live in Gubin, a Polish border town with a population of over 16,000. His wife works as a primary school teacher in Guben, on the German side of the border. Their children go to kindergarten in Poland and attend school in Germany. The family has friends and relatives on both sides of the border. As Konrad Bach says: “I really can say that I live in and between both countries.”

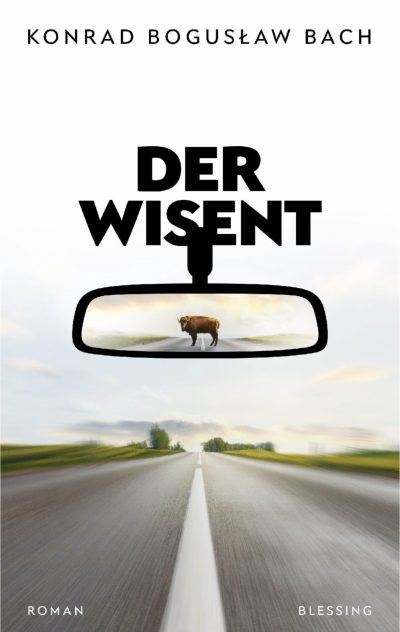

It’s therefore fitting that the subject of Bach’s first novel, published in 2022 when he was 40, is Polish-German relations. “Der Wisent” (“The Bison”) is a “road novel” funded by the Jürgen Ponto Foundation. Heniek, a mechanic in his early 60s, has been abandoned by his wife after 36 years of marriage. Together with the carpenter Andrzej, he sets out for Holland by car to try and bring her back. “I wanted to write a European homeland novel”, Bach explains. “In the end, the action only takes place in Poland and Germany, but the plot also includes characters from Spain or Greece. Also Holland, of course.” One important inspiration for the material came from three men whom Bach heard talking having a “hair of the dog” on the second day of a lavish Polish wedding. “The way they talked about global politics triggered something in me. There is a particular type of provincial Polish male that amuses and touches me. I wanted to create a homage to them that amuses and touches the reader.” What is the connection with the bison after which the book is named? Konrad Bach explains that in September 2017, a bison roamed freely through Poland, where it became quite a celebrity. As soon as the huge animal crossed the border into Germany, however, it was shot. “For me, this story is almost metaphorical. Not to mention the Europa myth with the bull.”

Bach wrote most of the novel during his daily commute on the train from Gubin to Frankfurt/Oder. “The journey lasted 40 minutes”, he says. “That’s why the novel consists of short, quick units.” The novel was also inspired by Bach’s desire to bring his Polish and German sides together, as well as his wish for people from both countries to meet each other as equals and with a sense of curiosity. In his words: “A lot of Polish people are very warm, straightforward and direct. They have the ability to not get bored and the willingness to have a good time with other people. That’s good for Germans, too.” When it comes to German people, he says, “It might sound strange, but in my experience, they are extremely open-minded. And intellectually, they are very open to new ideas. After all, alongside the Prussian tradition, you also have Romantic Germany, full of imagination and a love for nature. These two mentalities could complement each other very well.”

Konrad Bach is currently working on a new project, but would rather keep the details to himself for now.

Anselm Neft, June 2024