The Polish-Jewish prayer house in Remscheid 1928–1933

From the start of the 1880 Jews were forced to leave their homes in Eastern Europe as a result of anti-Jewish pogroms and increasing poverty. Their main destination was the USA, and for many of them Germany was simply a transit country. Nonetheless around 70,000 Jews from Eastern Europe had decided to settle in the German Reich by 1910. When the battles in the First World War raged, particularly in traditional Jewish areas in Poland, many people fled from the conflicts, were captured and enlisted by the German forces to work in industries that were vital for the war effort. At the end of the war the majority of the old Jewish areas were returned to the Polish State when the borders were redrawn once more. But when the laws and regulations issued by the Polish government made it difficult for Jews to take part in business activities and find a job in state services, this set off another wave of emigration. By 1933 a further ca. 88,000 Jews from Eastern Europe had settled in the German Reich.[2]

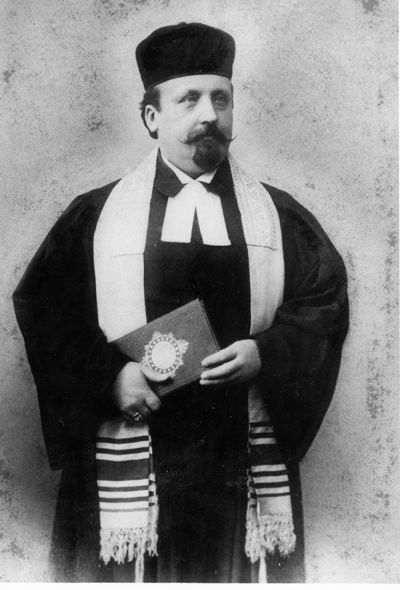

At the start of the 20th century Remscheid was an attractive place for Eastern European Jewish families to emigrate. Many orthodox families rejected the assimilated services in the long-standing Jewish congregations and initially gathered for services in prayer rooms in private houses. But as more and more Jews moved into the country the prayer rooms became too small to accommodate them and during the Weimar Republic a society named “Beth HaMidrasch” (Learning and Prayer House) was set up. In 1928 it succeeded in renting a small house in the courtyard of its own “People’s House” at 59/61 Bismarckstraße and, as was reported in the “Israelite Family Sheet”, set it up “with great and willing sacrifice which tested the congregation’s financial powers to the limit.”. One of their members, Heinrich Mandelbaum, painted the interior of the prayer house with traditional folkloric motifs that he knew from the small wooden synagogues back in Poland. Many of these motifs and quotations were widespread in the century-old country synagogues in Poland.[3] Heinrich Mandelbaum, who was born in 1881 in Slomniki[4] in the part of Poland that had been annexed by the Russians, had arrived with his family in Remscheid in 1914.[5]

[2] Maurer, Ostjuden, pp. 46-81. Numbers, p. 72. Backhaus, Gruppe der Ostjuden pp. 177-180.

[3] For the images in Polish rural synagogues see: Grunwald, Beschreibung der Malereien, and the same, Ikonographie.

[4] On the Jewish community in Slomniki see: Świętokrzyski Sztetl Ośrodek Edukacyjno-Muzealny at: http://swietokrzyskisztetl.pl/asp/en_start.asp?typ=14&menu=248&sub=173#strona

[5] Letter from Shlomo Shaked (Felix Mandelbaum) dated 4. March 1993 (Private ownership J. Bilstein, Remscheid). Bilstein, Ostjuden in Remscheid. And Ostjüdische Volkskunst. Pracht-Jörns, Remscheid, pp. 256-257.

Thanks to the photographs in the press article (see the mediatheque) and later descriptions given by former members of the congregation, the individual motifs of the unusual paintings and their Hebrew inscriptions in the German synagogue have been passed down to us. On the East wall right of the Torah shrine, on the left next to the window were two crossed schofars and two crossed violins. Above them were two Hebrew quotations from the Tehillim, Psalm 150.3 “Praise him with the sound of the shofar” and “praise him with the psaltery and harp”. On the south wall were two lions on the left and, on the right, a deer in a wood. Above them were the inscriptions: “bold as a lion” and “speedy as a deer”. On the extreme right of the south wall is an eagle, above which are the words “light as an eagle”. The illustrations refer to the Mishnah tractate “Pirkei Avot” (Chapters of the Fathers) 5.20, “Be bold as a leopard, light as an eagle, fleeting as a deer and mighty as a lion to do the will of your Father in Heaven.”[6]. Between the lion and the deer is a quotation from the Mincha prayer (afternoon prayer) on the Sabbath: “Thy Love is eternal justice, Thy love is truth! Thy love, oh God reaches to the heavens, with it Thou hast accomplished great things, oh God, who can be compared to Thee, Thy love is like powerful mountains, Thy justice like the great Flood, Thou givest sustenance to men and beasts, Eternal One.”[7]. To the left of the West wall were illustrations to the Chapters of the Fathers, Noah’s Ark and a dove with a branch, next to which was the rainbow, the symbol of God’s covenant never to send a flood to the Earth again. Above the Ark were the words “Noah’s Ark”; to the right and the left of the rainbow was a quotation from Genesis 9.13, “I have set my rainbow in the clouds”. On the right of the West wall were illustrations to the book of Jonah, the legendary Lake Tarshish, the ship in the storm and the whale which disgorged Jonah on the shore. Above the water are the words, “The Lake of Tarshish” and below the water, “and it [the whale] disgorged Jonah onto dry land”, a quotation from Jonah 2.11. The North wall depicts the cave of Machpela near Hebron. This was where the forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were buried with their wives Sarah, Rebecca and Leah. Above the illustration are the words “The cave of Machpela”.[8]

The article in the “Israelite Family Sheet” not only gives us an impression of the pictures in the Remscheid prayer house, it also gives us, from today’s perspective, an irritating impression of the way in which acculturated German Jews perceived their fellow believers in and from Eastern Europe. Sentences like “In eastern Jewish synagogues one can often find such naive portraits of an unadulterated, if admittedly unkempt folkloric art” and “These (hobby) painters […] embellish God’s house with the childish pleasure of carefree natures and more or less talented dilettantes, and where the art critic shakes his head with a smile, the cultural researcher makes interesting studies …”, illustrate the ambivalent relationship which ranged from arrogant rejection on the one hand to fascination on the other. Whereas in the 19th century all Jews who lived in the areas which made up the Polish-Lithuanian Union under the Jagiellon dynasty, were commonly known as “Polish Jews”, at the beginning of the 20th century this term was replaced by the words “East Jews”. That said, the term used in the article is more than purely geographical: it also conceals a stereotype. Many German Jews regarded the “East Jews” as representatives of Jewish ghettos, a way of life that they had long outgrown and that was culturally backward, religiously orthodox and clinging to out-of-date customs and traditions . A number of Jewish intellectuals, on the other hand, regarded the “East Jews” as representing pure, unadulterated Judaism and called on people to reflect on their own roots.[9]

[6] Translation in: Grunwald, Beschreibung der Malereien, p. 56.

[7] Translated in: Sidur Sefat Emet, p. 143.

[8] I should like to thank Frau Dr. Ursula Reuter (Salomon Ludwig Steinheim-Institut) for the translations of the inscriptions from the Hebrew.

[9] Maurer, Ostjuden, pp.11-16. For the image of “East Jews” see e.g.: Aschheim, Brothers and strangers. Kurth / Salzborn, Antislawismus und Antisemitismus. Panter, Selbstreflexion und Projektion. Rüthers, Sichtbare und unsichtbare Juden.

The Polish-Jewish prayer house on Bismarckstraße was only used as a religious centre for a few years. When Jewish society assets all over the country were confiscated after Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, Nazi organisations moved into the Remscheid People’s House and the prayer house had to be abandoned.[10] Henceforth, orthodox Remscheid Jews gathered for services in private prayer rooms. The increasing marginalisation and persecution of the Jewish population also hit Polish Jews who were subjected to particularly savage harassment by Nazi propaganda that talked of “East Jews” and “stinking Jews”. Many of the immigrants from Eastern Europe had sent their children to secondary education and now saw that there was no longer any future for them in Germany. And since they had no means to finance their children’s further education in other Western countries the only alternative was Palestine. So as early as 1933 young Jews began to leave Remscheid for Palestine with the help of Zionist organisations. The lack of savings – most Jews ran tiny businesses that provided just enough money to be able to live – was also a reason why the older generation and the tiny children remained in Germany: they simply could not afford to emigrate. In addition their prospects of obtaining a visa to emigrate to other countries in the west were very small, because the quota for Polish citizens for countries like the USA were almost non-existent.[11]

In autumn 1938 Polish-Jewish migrants were the victims of an utterly unexpected political development. In order to pre-empt the mass expulsion of Polish Jews from the German Reich the Polish government published an edict in October 1938 which removed Polish citizenship from all those who had lived abroad continuously for more than five years, if they had not obtained a special endorsement in their passports from their relevant Polish consulates by the 30th October 1938. When the authorities in Berlin learnt of this edict, on 27th October 1938 they issued a notice of expulsion to thousands of Polish Jews telling them they would be arrested within a few hours and deported over the Polish border either by foot or in collective transports. Between 15,000 and 17,000 people in the Reich were affected by this mass deportation, known as the “Poland action”.[12]

[10] The building was destroyed in the Second World War and the site was newly constructed. Verbal information from J. Bielstein, Remscheid.

[11] Bilstein, Juden in Remscheid, p. 89: and, Ostjuden in Remscheid, pp. 54-55.

[12] Tomaszewski, Jerzy: Auftakt zur Vernichtung, pp. 100-144. Tomaszewski, Jerzy.: Przystanek Zbąszyń.

Polish-Jewish families living in Remscheid were also affected by the expulsion. Whereas whole families were affected in other towns, in Remscheid it was almost exclusively men. Heinrich Mandelbaum, the man who had painted the pictures in the prayer house, was arrested on 28th October 1938, expelled to Neu-Bentschen on the borders of Poland and finally interned in the German-Polish border town of Zbąszyń. His son, Felix, had already emigrated to Palestine as a young man in1933. For years he attempted to get an exit visa for his parents and brother: and in 1938 he received the longed-for papers. Whereas Mandelbaum’s wife Riva and his son, Hans managed to get to Jaffa from Remscheid via Holland and France, Heinrich Mandelbaum was refused a transit through the German Reich; and finally escaped to Palestine via Romania.[13] He was one of the few Polish Jews who managed to emigrate to a country outside Europe after they were expelled. Most of the Remscheid Jews, and their families who were expelled from Germany in the following months, were annihilated after the German invasion of Poland. The sole reminder of the former Polish-Jewish congregation in Remscheid, alongside the reminiscences of the few people to survive, was the article in the Israelite Family Sheet “East Jewish Folkloric Art in Germany”.[14]

Sabine Krämer, May 2017

[13] Heinrich Mandelbaum died on 11. March 1956 in Israel. (Written information from his granddaughter in Israel.) His daughter Anna, married name de Swarte, lived in Holland, from where she was deported to Auschwitz and murdered. Mandelbaum’s sons, Robert und Max, and his daughter Erna, married name Fischbein, also emigrated to Palestine. See Bilstein / Backhaus, Names and dates, p. 218.

[14] Backhaus, Gruppe der Ostjuden, pp. 186-188: and Polenaktion, pp. 2-4. Bilstein, Juden in Remscheid, pp. 104-164.

Further reading

Aschheim, Steven E.: Brothers and strangers. The East European Jew in German and German Jewish consciousness, 1800-1923, Madison 1982.

Backhaus, Frieder: Die Gruppe der Ostjuden in Remscheid, in: Geschichte der Remscheider Juden. (Hrsg.) Jochen Bilstein and Frieder Backhaus, Remscheid 1992, pp. 177-188.

Backhaus, Frieder: Die „Polenaktion“ (Teil 2) in: Remscheider General-Anzeiger, Beilage „Geschichte and Heimat“. Mitteilungsblatt des Bergischen Geschichtsvereins, 71. Jg. Nr. 2 2004, pp. 1-4.

Bilstein, Jochen: Die Juden in Remscheid in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, in: Geschichte der Remscheider Juden. Hrsg. v. Jochen Bilstein u. Frieder Backhaus, Remscheid 1992, pp. 55-175.

Ders. u. Backhaus, Frieder: Namen und Daten jüdischer Bürger Remscheids zwischen 1933 and 1944, in: Geschichte der Remscheider Juden. Hrsg. v. Jochen Bilstein u. Frieder Backhaus, Remscheid 1992, pp. 206-228.

Bilstein, Jochen: Ostjuden in Remscheid, in: Hier wohnte Frau Antonie Giese. Die Geschichte der Juden im Bergischen Land, (ed) Trägerverein Begegnungsstätte Alte Synagoge Wuppertal, Wuppertal 1997, pp. 50-55.

Ders.: Ostjüdische Volkskunst in Remscheid, in: Remscheider General-Anzeiger, supplement „Geschichte und Heimat“. Mitteilungsblatt des Bergischen Geschichtsvereins, 60. Jg. Nr. 2 1993, pp. 1-2.

Grunwald, Max: Beschreibung der Malereien in den Synagogen Polens, in: Breier, Alois; Eisler, Max; Grunwald, Max: Holzsynagogen in Polen, Wien 1934, pp. 49-60. At: http://www.europeana.eu/portal/de/record/09320/1BC53FF9541E269D7EFDF96DC5E1D7487BA92A32.html

Ders: Zur Ikonographie der Malerei in unseren Holzsynagogen, in: Breier, Alois; Eisler, Max; Grunwald, Max: Holzsynagogen in Polen, Wien 1934, Anhang pp. 1-23. At: http://www.europeana.eu/portal/de/record/09320/1BC53FF9541E269D7EFDF96DC5E1D7487BA92A32.html

Kurth, Alexandra; Salzborn, Samuel: Antislawismus und Antisemitismus. Politisch-psychologische Reflexionen über das Stereotyp des Ostjuden, in: Hahn, Hans-Henning u.a. (eds.): Deutschlands östliche Nachbarschaften. Eine Sammlung von historischen Essays für Hans Henning Hahn, Frankfurt am Main, New York 2009, pp. 309-324.

Maurer, Tude: Ostjuden in Deutschland 1918-1933, Hamburg 1986.

Panter, Sarah: Zwischen Selbstreflexion und Projektion. Die Bilder von Ostjuden in zionistischen und orthodoxen deutsch-jüdischen Periodika während des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 59 (2010), pp. 65-92.

Pracht-Jörns, Elfi: Article „Remscheid“, in: ibid.: Jüdisches Kulturerbe in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf, Köln 2000, pp. 256-261.

Rüthers, Monica: Sichtbare und unsichtbare Juden - eine visuelle Geschichte des „Ostjuden“, in: Osteuropa 60/1 (2010), pp. 75-93.

Sidur Sefat Emet, translated by Selig Bamberger, Basel 1956/1960.

Tomaszewski, Jerzy: Auftakt zur Vernichtung. Die Vertreibung polnischer Juden aus Deutschland im Jahre 1938, Osnabrück 2002.

Tomaszewski, Jerzy: Przystanek Zbąszyń, w :Olejniczak, Wojciech; Skórzyńska, Izabela (Red.): Do zobaczenia za rok w Jerozolimie. Deportacje polskich Żydów w 1938 roku z Niemiec do Zbąszynia, Zbąszyń 2012, pp. 71-83.

![South wall on the left with illustrations of the Mishneh tractate ‘Pirkei Avot’ [Chapters of the Fathers] South wall on the left with illustrations of the Mishneh tractate ‘Pirkei Avot’ [Chapters of the Fathers] - In: „Aus alter und neuer Zeit“.](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/suedwand_links.jpg?itok=2lMG07mE)