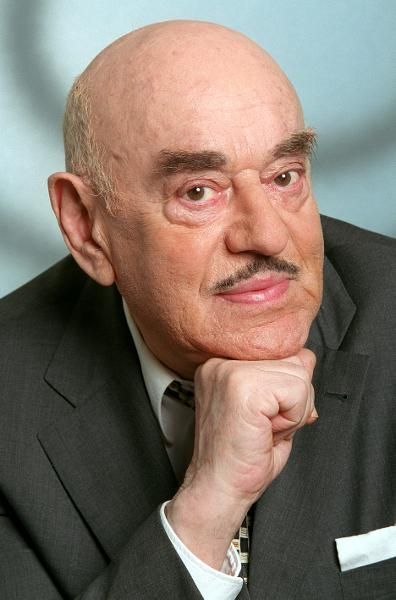

Marek Pelc. A Polish-Jewish poet in Frankfurt/Main

Marek Pelc was born on 10 April 1953 to a Jewish family in Wrocław. He has a half-sister, Zofia, who is eight years his senior. His mother, Eugenia Pelc, née Lis (1924–2018) came from Brok on the Bug river, a town 100 km to the east of Warsaw. When she was 14, she joined the Jewish socialist “Bund” in Poland, and spent the war years in the town of Pensa in the Ural mountains. His father, Mateusz Pelc (1923–1987), was born in Zamość, but grew up in Novosibirsk in the Soviet Union. It was thanks to their relocation to Russia that his parents survived the Holocaust. In an interview for the “Jüdische Allgemeine” newspaper, Pelc explained that he came from a politicised family.[1] In 1945, his mother returned to Poland, where she settled in Wrocław in Lower Silesia. At that time, those Jews who had survived tended to choose Lower Silesia (Dolny Śląsk) as their home, since here, they felt relatively safe in post-war Poland. Marek’s father returned from Russia somewhat later, in around 1950. Eugenia Pelc then worked for many years as a consultant on the executive board of the “Społem” Wrocław cooperative. Her husband was a stage manager in the Polish Theatre (Teatr Polski) and was also responsible for organising the logistics of the theatre company’s popular tours.

Marek Pelc attended the Jewish school in Wrocław, which was housed in the building of what was then Grammar School no. 7 on Jizchok Leib Perez Square (Plac Icchoka Lejba Pereca). In addition to the standard range of subjects, pupils at the school also learned Yiddish and Jewish history. During that time, he also took part in holiday camps, including in Elbląg and Żabno near Tarnów, which were organised by the Jewish Friendship Circle (Towarzystwo Społeczno-Kulturalne Żydów, TSKŻ), which in turn was supported by an aid organisation from the US, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, or simply “Joint” for short. Most of Marek’s fellow pupils were from Jewish families in Wrocław.

Emigration in 1968

In 1969, in the wake of the anti-Semitic campaign in Poland, which only intensified after the Six-Day War in Israel in 1967 and which finally boiled over throughout the country, Marek’s mother lost her job. Although the Pelc family did not own a television, Marek remembers the famous speech tinged with anti-Semitism by Władysław Gomułka, who was then Secretary General of the Polish United Workers’ Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR). He heard the speech by chance as he was passing a shop in Wrocław that sold televisions. That same year, his parents decided to leave Poland for good. It was his mother above all who made the decision, while his father was more hesitant about emigrating. In 1969, Marek had just completed his ninth year at Grammar School no. 4 in Wrocław. His half-sister Zofia emigrated to Denmark with her husband.

According to the law at the time, those wishing to emigrate were required to give up their Polish citizenship; only then were they presented with travel documents, which expressly excluded any possibility of ever returning. The Pelc family therefore cleared their apartment, tied up any organisational business that needed to be completed, and in November 1969, boarded a train to Vienna. There, they spent two days in a transit camp in Schloss Schönau palace, where the Israeli immigration authority also had an office. On 12 November 1969, the family landed at Tel Aviv airport. They had relatives in the city.

In Israel

Immediately on arrival in Israel, the stateless new arrivals were granted Israeli citizenship. The Pelc family were given an apartment in a duplex building in Upper Nazareth (today: Nof HaGalil), which was unfortunately some way away from their relatives in Tel Aviv. Marek attended a language school in the Bar'am kibbutz on the border with Lebanon. His mother was assigned a different kibbutz. At first, his father remained in the new apartment, but later returned to Europe, where he initially stayed in Denmark. From there, he moved on to Germany, to Frankfurt/Main.

After a year in the kibbutz, Marek Pelc continued his education with other new arrivals from Poland in an evening college in Holon. During this time, he lived with his mother in Petah Tikva near Tel Aviv. In 1971, he passed his school-leaving exams and was conscripted into the army. He then served in the Israeli army for three years. Then, in 1975, he enrolled at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he studied philosophy and history. Since he had little monetary support from his father, he got by financially by doing various odd jobs, usually cleaning peoples’ apartments. At the same time, from 1975 to 1977, he worked in the Israeli National Library in Jerusalem. In 1979, Marek completed the first part of his studies, obtaining a Bachelor of Arts. Since at that time it was no easy task finding work with his two degree subjects, he changed course and began practical training as a masseur. It was in this role that he earned his living, including in a Turkish bath in Jerusalem. In 1980 and 1981, he travelled to Europe for a year, where he again made ends meet by taking on odd jobs. He first stayed in Denmark, then in Germany, and finally in France, where he was hired to help out with the grape harvest. On his return to Israel, he moved into his mother’s apartment, who had now moved to Denmark to be with her daughter there. He continued his studies and obtained his Master of Arts degree.

In Frankfurt/Main

In 1982, Marek Pelc returned to Germany to visit his father in Frankfurt/Main. During that time, war broke out between Lebanon and Israel (the First Lebanon War). Marek decided to remain in Germany and to continue his studies there. With this aim in mind, he threw himself into learning the German language. After passing his language exam, he enrolled at the Goethe University Frankfurt, where he studied German language and literature. This study, too, was mainly self-funded. The Pestalozzi Foundation had only granted him a small, temporary stipend.

In 1983, he made the acquaintance of Polish émigrés who had migrated to Frankfurt following the imposition of martial law in Poland, and who worked on the editorial board of the “Przegląd Tygodnia” (“Weekly Review”), which appeared in Polish.[2] He then joined the magazine himself, remaining there for seven years as a permanent member of staff and contributing short stories, feuilleton-style articles and poems. The other members of the editorial board were Wiesław Bicz, Urszula Wierzbicka and Krzysztof Wierzbicki, who was responsible for the layout. The magazine continued to be published throughout his time there and was sold in places where Poles typically met, such as the “Polish” church. In 1989, Marek Pelc completed his German studies with the overall grade “good”. His Master’s thesis, supervised by Professor Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow, was entitled “Elias Canetti as an enemy of death”.

The fate of the Jews and Marek Pelc’s own identity

During the late 1990s, Marek Pelc spent four years working on a research project at the Fritz Bauer Institute of the History and Impact of the Holocaust (Fritz Bauer Institut zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust), for which 2,400 photographs of Jews from Będzin and Sosnowiec were scrutinised which were found in Auschwitz [after 1945 - translator’s note] and are now held in the museum in Oświęcim (formerly Auschwitz). These images formed the basis for the documentary film “... Forgive me, I’m alive” (original title: “Przepraszam, że żyję”), for which Marek Pelc and the director Andrzej Klamt wrote the script. In 2000, the filmmakers were awarded the prestigious Hesse Film Prize.

Pelc was also a research assistant for the first Jewish children’s book to appear in Germany since 1945.[3] During that time, he also translated poetry and prose by Jehuda Amichai, Natan Zach, Admiel Kosman, Lea Goldberg and Dalia Ravikovitch from the original Hebrew into Polish.

In 1995, he began training as a psychoanalyst at the Frankfurt Institute of Psychoanalysis, during the course of which he himself underwent analysis as a trainee. In 2001, he terminated his training for financial reasons. He also worked for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation during this period, conducting more than 30 interviews lasting several hours with survivors of the Holocaust in Germany and Denmark which were documented in professional films.

Marek Pelc has been married to Marina Shkolnikova, a Russian, since 2006. They met in Frankfurt when she came to the city for research purposes after obtaining her doctorate in philosophy at the University of St. Petersburg. However, once in Germany, and after she and Marek had become a couple, she decided to study law; today, she works as a lawyer. As Marek likes to joke when talking about his wife: “Frankfurt is halfway between St. Petersburg and Tel Aviv”.

Usually when he travelled, it was to Israel and Poland. In Israel he has friends and family whom he visits every year. With a smile, he says, “for years, I’ve been travelling to Lisbon and every time I end up in Tel Aviv”. On multiple occasions, he also participated in meetings of the Polish-Jewish emigrants of 1968 which are held in Israel as part of the “Reunion Initiative”.

His poetry

Even as a very young boy, Marek Pelc was already composing poetry in Polish. Today, he also writes in Hebrew and German. He made his literary debut in 1982 in “Przegląd Tygodnia” in Frankfurt, while at that time, he was also being published in Poland in the “Czas Kultury” (“Time of Culture”) magazine.[4] Some of his poems are also included in the dual-language anthology “Napisane w Niemczech. Geschrieben in Deutschland” (“Written in Germany”), which appeared in 2000.[5] In 2015, the Paris-based publishing house Éditions yot-art issued a volume of poetry as part of its “Recogito” series entitled “Czarnowidzenia” (“Seeing Black”), with Marek Wittbrot, a Pallottine, who was editor-in-chief of the Polish-language magazine “Recogito” in France, a driving force at the Centre for Dialogue (Centre du Dialogue) in Paris, and who also wrote the afterword.[6] The illustrations for this volume were created by Artur Majka.

In his writing, Marek Pelc repeatedly takes up motifs such as memory, transience and unfamiliarity, archetypes of Jewish-Christian culture in which the Holocaust sometimes resonates as an echo in his poems. As Marek Wittbrot writes in the afterword to “Czarnowidzenia”: “Like the Jews who went in search of a new land which offered so much more than the affluence of Egypt and yet also something different from it, and like Aeneas, who set out from Troy on a journey into the unknown, Marek Pelc, ‘by the hand of fate, a refugee’[7], as descendent and inheritor of the few who survived the annihilation, chose a hazardous path. While he may not have reached the Lavinian shore, he did succeed in arriving at the foothills of Hesse, in a sense at the border posts mentioned by Tacitus in monte tauno, where human fates have already frequently crossed in history. However, he never turned away from the past, and always remained connected to his roots. His poems are like a band of light / above a thicket / of dark contours. Another silent scream that cannot be described in words. Yet there is no doubt that it is there. It cannot be suppressed. It fills not only existence, not only memory, not only the bodies”.[8]

Joanna de Vincenz, August 2022

Marek Pelc

I live in a foreign city

and am surprised that the roads

seem so familiar, that the light from the streetlamps

shines on the paving - like yesterday

like a week ago. Today, I walked

again across the iron bridge

to the other side of the Main.

Thereafter, an invisible net enveloped me

of unclear memories -

Bridges over the river in my hometown.The palpable reality of a foreign city is

always painful. Early in the morning, for example,

you buy a loaf of rye bread in the bakery around the corner

count the money in a foreign language

but still clearly feel the dormant sounds

of another within you.How long - you ask - can you

live in a foreign city without

allowing it to break into your soul?

How long can you look into faces

and hear the babble of voices on the street

without feeling that it is a part of you?And yet, this is a foreign city

you sense it, and yet you cannot explain it -

perhaps because there is nowhere

where you are at home.Because home is not a place

but only a grievance of the soul.

From the volume of poetry “Czarnowidzenia”, Paris 2015 – translated from the Polish/German by the translator.

***

again we are together

in Jerusalem

I hold you

in open arms

without doubts

that it is possible

(in dreams, everything is possible)in the morning

I open the iron window shutters

the cats are already warming themselves

in the sun near the refuse bins

a young tree trembles lightly in the wind

the outline of the walled slope

opposite the house

and on the wall

the plant, finger-like, winds its way

known here as

“Wandering Jew”10 February 1987

From the anthology “Napisane w Niemczech. Geschrieben in Deutschland“, Jestetten 2000 – translated from the Polish/German by the translator.