The Lexicon of Polish life in Germany

One of the most important projects undertaken by the Union of Poles in Germany was the preparation and printing of the “Lexicon of Polish Life in Germany”. The idea for the project was born around 1930 when restrictions were being increasingly imposed on the social and cultural life of Poles in Germany. The council of the Union decided to collect material on the geographical distribution of Poles in Germany, and the social, cultural and economic life of the Polish Diaspora. In addition they were interested in extending this material with information about demonstrations against Poles. An editorial team was quickly set up. Despite many difficulties, including financial problems, work on the lexicon was completed in 1938. Nonetheless the book was not printed in Poland because the Foreign Office feared that this could muddy German-Polish relationships. The book was finally printed in Opole. That said the outbreak of war prevented the project from being entirely completed. The whole edition was confiscated and destroyed by the Nazi authorities. A reprint of the rescued book first appeared in Poland in the 1970s. The lexicon is an important source on the destiny of Poles in Germany in the second half of the 1930s.

The increasing violation of the rights of Poles living in Germany, the alleged deliberate reduction of their numbers in the census of 16th April 1933 and finally the destruction of their property (particularly after Hitler’s seizure of power) motivated the Central Union of Poles in Germany (ZPwN) to document the riots in a card index. In this way the organisation attempted to rescue texts and pictures on Polish life in Germany from destruction.

In order to meet this aim a special department was set up in early 1933. This consisted of Jan Łangowski and Stefan Murek, assisted by the typists Eleonora Bednarkiewicz and Helena Lehr. Edmund Osmańczyk and Edmund Kaczmarek joined the department in autumn 1933. Financial problems meant that the department was unable to take on any further staff. The existing staff were dependent on the help of Poles, above all their fellow countrymen who were studying in Germany. The group wanted to record all the places where Poles had lived. In addition they were interested in their cultural life and also made a particular note of Polish monuments. During the work someone came up with an idea for a lexicon, i.e. an alphabetical list of places with reference to the aspects mentioned above. When they were trying to put together the different Polish places they encountered difficulties because of their German names. For this reason it was agreed that all German place names with a Polish equivalent would only be quoted with a note, e.g.: “Borek, German name Walddorf until 1935, a village in the district of Kluczbork, Opole Silesia. Number of Poles according to the 1910 census: 158 (XVI, XXVIII)”. The Roman numbers point to the Polish and German sources, a list of which was to be printed at the end of the lexicon. (This list has been lost).

The foundation of the Slavic Bank (Bank Słowiański) in Berlin in 1934 changed the financial situation of the Union of Poles in Germany. It also had an effect on the work of the editors of the lexicon because the bank provided them with the means to finance their project. One year later in the press headquarters of the Union of Poles in Germany a photo department was set up with Aleksander Kraśkiewicz and Stanisław Otto Kałus, and it was not long before the first photos were available to the editors. In 1935 the department moved to new rooms in Potsdamer Straße, and this made the work on the lexicon considerably easier. The upshot was a more precise definition of the contents of the lexicon. Now the register of local places was extended by a general factual register.

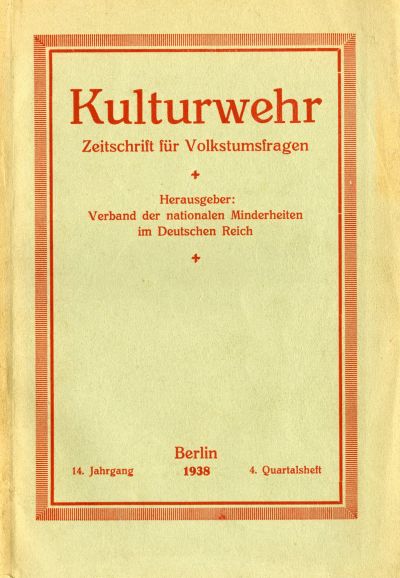

In autumn 1935 Edmund Osmańczyk became the editor-in-chief and the editorial team was gradually joined by new staff. In this connection it is important to point out that all the staff were very young (average age 19-22) and had no specific training for the job. Very often the staff would ask for advice from older members of the Union. The work itself often had to be done clandestinely in order to avoid the notice of the German authorities. Parallel to this the council of the Union was closely recording German intrusions and violations of minority rights of the Polish population in order to publish them in “Kulturwehr”. The information was also included in the lexicon, which explains the many legal articles and memoranda to be found there. The mobilisation law of 16th March 1935 interrupted the work on the lexicon. Much of the work planned for 1936-37 – like sifting and collecting statistical data from the Prussian archive – could not take place and this left a gap in the register of local places. The areas they examined included West and East Prussia and Opole Silesia. Other areas were not considered. A close look at the results from the different censuses reveals many shortcomings in the lists. Hence the staff working on the lexicon concentrated on ascertaining the true number of Poles living in Germany.

The 15th anniversary of the foundation of the Union on 3rd December 1937 was coming closer and the council put pressure on the editors of the lexicon to complete their work beforehand. The text had to be extended by the anniversary material and the decisions made at the First Congress of the Union of Poles in Berlin in 1938. After the congress the delegation of the World Union of Poles Abroad (Światpol) familiarised itself with the material gathered by the editors and offered to publish it in Poland. The board of the Union agreed to this suggestion and the editors began to prepare the final version of the lexicon. In mid-June the completed manuscript, consisting of over 1500 pages, was sent to Warsaw. The photos were to follow.

By autumn the editors had still received no answer. During this time they set up a card index of additional material in order to keep the lexicon up to date. The events of 1938 in Germany (the annexation of Austria and the mobilisation of the young men who been excluded from national service by the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles during the Weimar Republic) had a knock-on effect on the work of the editors of the lexicon. At the end of the year the headquarters of the Union received a report from Warsaw that Światpol regarded the publication of the lexicon as impossible. The Foreign Office in Warsaw had refused to consent to the publication of the lexicon since it considered that this would disturb the relationship between the Germans and the Poles. In this situation the council of the Union decided to go ahead and print the lexicon at their own expense in the “Nowiny Codzienne” (Daily Review) publishing house in Opole. Jan Łangowski, the paper’s editor-in-chief and first editor of the lexicon was given a credit by the Slavic Bank in order to purchase the necessary paper and printing ink, ostensibly for a “Kalendarz Spółdzielczy” (Comrades Calendar) for 1940. The printers began to lay out the large manuscript alongside their daily work. For practical reasons the text was set in two columns in a newspaper format. An edition of 5000 was planned, one hundred of which were to be printed on shiny paper where the photos were sure of a higher quality. Around 1299 photos were collected for publication.

The first sheet was printed in May; the last – the 19th of the 30 which were planned – in August 1939. The 20th sheet should have been printed on 1st September 1939. The corrections were made locally in order to avoid arousing the attention of the German police by sending it by post.

After the Germans invaded Poland the publishing house was occupied by police on 1st September, the printed sheets of the lexicon were discovered and the publishing house sealed off. However, one of the printers, Jan Trzeciok, managed to rescue a complete layout of the sheets which had already been printed and he hid them in his house. Shortly afterwards an order came from Berlin to Opole to destroy the whole edition along with the manuscripts. The order was carried out in September 1939.

During the Second World War a few individual sheets were rescued by accident. At the end of the war Jan Trzeciok handed over the hidden sheets to the editor Edmund Osmańczyk and, after many difficulties (including a lack of interest), the saved sheets were first published in Poland in the early 1970s.

The manuscript of the lexicon was thought to have been destroyed. By a happy accident it was discovered by the author of this article in a German library. Amongst others it consists of the missing article. This manuscript will form the basis for a book. The complete lexicon will soon be published by the University of Wrocław as part of the work of the Willy Brandt Centre for German and European Studies.

Krzysztof Ruchniewicz, June 2014