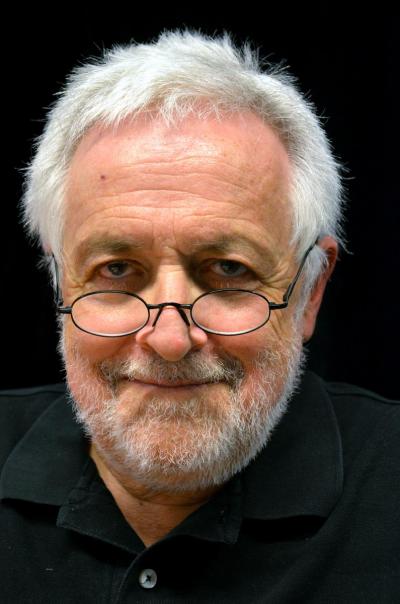

Raphael Lemkin. The man who coined the term “genocide”

Raphael Lemkin was born Rafał Lemkin on 24 June 1900 to a Polish-Jewish family of modest means in Bezvodne, a village in the Volkovysk region, not far from Grodno in what is now Belarus. His father, Józef Lemkin, leased a farm, which was unusual at that time for someone of his faith. In his autobiography, “Totally Unofficial”, Lemkin described the area in which he was born as follows: “I was born in a part of the world historically known as Lithuania or White Russia, where Poles, Russians (or, rather, White Russians), and Jews had lived together for many centuries. They disliked each other and even fought, but in spite of this turmoil they shared a deep love for their towns, hills and rivers. It was a feeling of common destiny that prevented them from destroying each other completely”.[1]

Even as a child, Raphael Lemkin was fascinated by history. One of the first books that influenced the decisions that he would make later in life was “Quo Vadis” by Henryk Sienkiewicz. Lemkin was so impressed by the novel that he started to search for similar examples of persecution in the history of mankind. “I was fascinated by the frequency of such cases, by the great suffering inflicted on the victims and the hopelessness of their fate, and by the impossibility of repairing the damage to life and culture”, he wrote in his memoir.[2] As a teenager, he experienced the barbarity of war first hand when Volkovysk town and the surrounding region were occupied by the Germans in 1915. However, he managed to escape to Białystok, where he attended the grammar school, completing his school education in 1919. Shortly afterwards, the Polish-Soviet war broke out, and the fresh-faced school graduate joined a medical corps of the Polish Army near Volkovysk. After the war, he first went to Kraków, where he studied law at Jagellonian University. In 1921, he moved to Lwów (now Lviv), where he enrolled at the Faculty of Law at Jan Kazimierz University. During this time, he attended seminars held by highly-regarded professors of law, such as Juliusz Makarewicz and Leon Piniński. In 1922, Lemkin also translated the Soviet Penal Code into Polish. His many travels, some for research purposes, took him to Berlin University and the Sorbonne. In 1926, he enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy in Heidelberg.

The start of his life’s work

The events of the 1920s further fuelled Lemkin’s interest in issues relating to criminal responsibility for the destruction of population groups and entire peoples. He was particularly impacted by the shooting of Talaat Pasha on the street in broad daylight in Berlin in 1921. The former Turkish minister of the interior [during the First World War] was the person who bore the main responsibility for the genocide of the Armenians. The gunman was a young Armenian who had lost 89 members of his family during the massacres of 1915–1917 (the word “genocide” did not yet exist during that time - author’s note). Talaat Pasha was living under a false name in Berlin, and it was not possible to try him before a court for his crimes. Instead, he was merely sentenced to death in Armenia in absentia. The fundamental principle of the sovereignty of states meant that it was impossible to find someone guilty of ethnically motivated murder committed in a different country.

“Why is a man punished when he kills another man, yet the killing of a million is a lesser crime than the killing of an individual?”[3] This was the question that Raphael Lemkin put to one of his professors at the university in Lwów, and it set in motion the task to which the ambitious lawyer would dedicate his life: the creation of a legal basis for the unification of moral and legal standards regarding the destruction of national, racial, and religious groups.[4] Lemkin knew that it would not be possible to realise his objective without supporters, and he set out to make the necessary contacts. During this time, he also quickly gained status in his legal career, becoming deputy public prosecutor of Warsaw in 1929. Soon afterwards, he was promoted again, this time to secretary of the penal section of the Polish Committee on Codification of Laws (Komisja Kodyfikacyjna RP), where he worked on the development of the Polish penal code. He was also a representative of the International Bureau for the Unification of Penal Law, where he worked with the most prestigious lawyers in western Europe. Then, in October 1933, at the international conference for the unification of penal law in Madrid, he took steps to push through his concept for the recognition of the annihilation of ethnic, religious or racial groups as a crime. His decision to do so was triggered by the political situation in Europe at the time: “Hitler had already promulgated his blueprint for destruction. Many people thought he was bragging, but I believed that he would carry out his program if permitted. The world was behaving as if it were ready to acquiesce in his plans. The Polish government was negotiating a non-aggression pact with Germany. In the circles of the League of Nations, my friends were making sarcastic remarks about the pact, which they thought would undermine collective security. Now was the time to establish a system of collective security for the life of the peoples.”[5]

[1] Frieze, Donna-Lee (ed.): Raphael Lemkin. Totally Unofficial. The Autobiography of Raphael Lemkin, Yale University Press New Haven & London, 2013, p. 3.

[2] Ibid., p. 1 f.

[3] Brockschmidt, Rolf: Das unfassbare benennen, in: “Tagesspiegel”, 13/2/2022, URL: https://www.tagesspiegel.de/wissen/wie-raphael-lemkin-den-genozid-begriff-praegte-das-unfassbare-benennen/28062128.html (last accessed on 7/4/2022).

[4] Frieze, Donna-Lee (ed.): Raphael Lemkin. Totally Unofficial, p. 19.

[5] Ibid., p. 22.