Józef Brandt

Mediathek Sorted

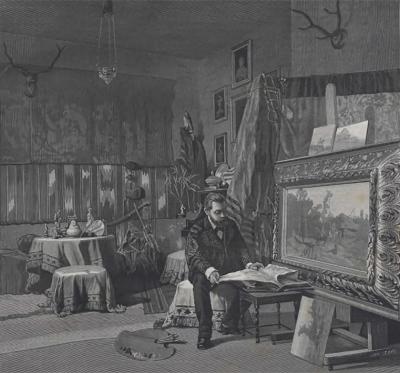

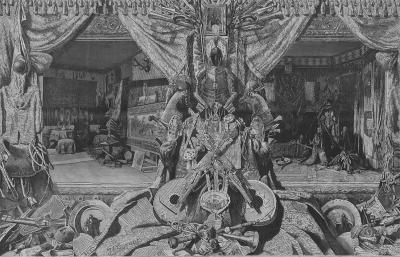

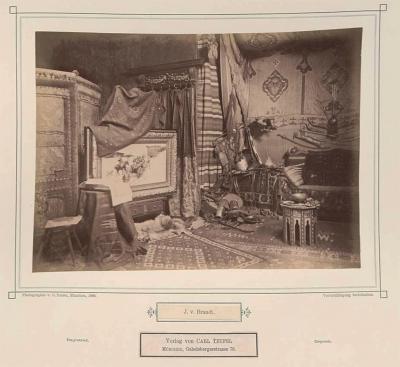

Thanks to contemporary reports, including letters from Brandt himself, we know a great deal about the furnishings, the function of the individual rooms and what took place there. When he was nine years old Andrzej Daszewski, one of his grandsons, saw the studio and wrote about it later.[3] On one side of the corridor there were two painting studios. The larger one was equipped with oriental sofas, a table with inlays and furniture from the 16th and 17th centuries. It was decorated with numerous weapons and armour. The walls were covered with a Turkish tent and there was a Persian rug on the floor. Easels and shelves for the paint and the brushes served as painting utensils. The painter Władysław Szerner (1836-1915), a friend of Brandt, worked for many years in the second studio, where Brandt stored his armour and musical instruments. When Brandt was away - and this was mostly the case as the Polish painter Anna Bilińska (1857-1893) wrote about a trip to Munich in 1882 - Szerner admitted visitors and acted as an official curator of the collection.[4] Opposite there was a room for storing costumes, graphics and books, while another room housed an exemplary arsenal of historical weapons, armour and regimental banners from various European countries. The walls there were also covered with a Turkish tent.

Like Makart, Brandt also used his studio for celebrations and welcoming members of the royal family. In a letter to his mother in Poland in 1876, he wrote that he had celebrated his name day in the studio with pupils and artist friends (especially from the Polish colony), like Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz and Szerner. On the following Monday Prince Luitpold had visited him personally to offer him his best wishes. At the carnival celebration of the Munich artists under the motto "A Court Festivity for Charles V.", in which Makart and members of the royal family were also involved, he caused a great sensation by equipping a Turkish troupe with props from his studio.[5]

Prince Luitpold of Bavaria (1821-1912), who had been Prince Regent since 1886, was known for his love of paintings. His unexpected visits to the studios, including those of young artists, through whom he got to know a large part of the Munich artists' community, were an early passion that he retained for decades and which became legendary during the years of his reign.[6] As Prince Regent he promoted the arts by creating foundations, and constructing numerous cultural buildings like the new building for the Academy of Arts (1886) and the Bavarian National Museum (1893-1900). He was also an important art collector. In an almost inflationary manner he appointed artists as professors and elevated them to the rank of nobility by awarding them the Bavarian Order of Merit. Two-thirds of the newly appointed academy professors held nobility titles.[7]

[3] Andrzej Daszewski: Zbiory militariów Józefa Brandta, in: Muzealnictwo Wojskowe, Warschau 1985, page 68-76. The Jacek Malczewski Museum in Radom/Muzeum im. Jacka Malczewskiego w Radomiu posesses photos of the studio taken in 1915; there is an illustration by Agnieszka Bagińska (see note 1) on page 47. On the genealogy of Józef Brandt cf. http://www.sejm-wielki.pl/b/zi.4.7.b (called up on 2.11.2017).

[4] Agnieszka Bagińska (see note 1), page 44

[5] Daszewski 1985 (see note 3), pages 60, 62; Agnieszka Bagińska (see note 1), page 45

[6] Birgit Jooss: „Ein Tadel wurde nie ausgesprochen“. Prinzregent Luitpold als Freund der Künstler, in: Ulrike Leutheusser/Hermann Rumschöttel (editors): Prinzregent Luitpold von Bayern. Ein Wittelsbacher zwischen Tradition und Moderne, München 2012, pages 152, 167

[7] Ibid, page 159 f.

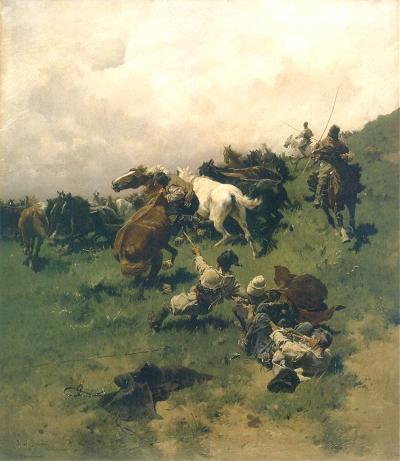

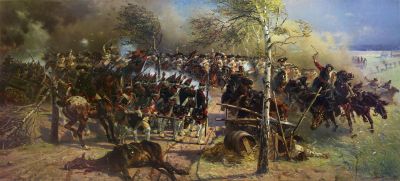

![Fig. 25: The Liberation of Prisoners, 1878 Fig. 25: The Liberation of Prisoners, 1878 - The Liberation of Prisoners [from the hands of Tatars], 1878. Oil on canvas, 179 x 445 cm, National Museum Warsaw/Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie](/sites/default/files/styles/width_100_tiles/public/assets/images/25_befreiung_der_gefangenen_1878_mnw_cyf.jpg?itok=i5_t7XqM)